2019 ATB

For each electricity generation technology in the ATB, this website provides:

- Capital expenditures (CAPEX): the definition of CAPEX used in the ATB and the historical trends, current estimates, and future projections of CAPEX used in the ATB

- Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs: the definition of O&M and the current estimates and future projections of O&M used in the ATB

- Capacity factor (CF): the definition of CF and the historical trends, current estimates, and future projections of CF used in the ATB

- Future cost and performance methods: an outline of the methodology used to make the projections of future cost and performance in the ATB for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases

- Levelized cost of energy (LCOE): metric that combines CAPEX, O&M, CF, and projections for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases for illustration of the combined effect of the primary cost and performance components and discussion of technology advances that yield future projections

- Financing assumptions: development of technology-specific interest rate on debt, return on equity, and debt-to-equity ratios and their impact on LCOE are documented in each technology section, where applicable, and summarized here.

Electricity generation technologies are selected on the left side of the screen, and the topics highlighted above can be selected using the drop-down menu at the top right of the screen.

Guidelines for using and interpreting ATB content and comparisons to other literature are provided. LCOE accounts for many variables important to determining the competitiveness of building and operating a specific technology (e.g., upfront capital costs, capacity factor, and cost of financing); however, it does not necessarily demonstrate which technology in a given place and time would provide the lowest cost option for the electricity grid. Such analysis is performed using electric sector models such as the Regional Energy Deployment Systems (ReEDS) model and corresponding analysis results such as the NREL Standard Scenarios.

The NREL Standard Scenarios, a companion product to the ATB, provides a suite of electric sector scenarios and associated assumptions, including technology cost and performance assumptions from the ATB.

ATB data sources and references are also provided for each technology. All dollar values are presented in 2017 U.S. dollars, unless noted otherwise.

Additional information is available here: About the 2019 ATB.

Offshore Wind

Representative Technology

In 2016, the first offshore wind plant (30 MW) commenced commercial operation in the United States near Block Island (Rhode Island). In 2018, Vineyard Wind LLC and Massachusetts electric distribution companies submitted a 20-year power purchase agreement (PPA) for 800 MW of offshore wind generation and renewable energy certificates to the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities for review and approval. In the ATB, cost and performance estimates are made for commercial-scale projects with 600 MW in capacity. The ATB Base Year offshore wind plant technology reflects a machine rating of 6 MW with a rotor diameter of 155 m and hub height of 100 m, which is typical of European projects installed in 2016 and 2017 and the turbine rating installed at the Block Island Wind Farm (GE Haliade 150-6MW).

Resource Potential

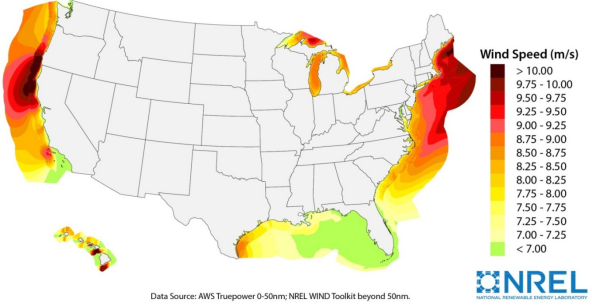

Wind resource is prevalent throughout major U.S. coastal areas, including the Great Lakes. The resource potential exceeds 2,000 GW, excluding Alaska, based on domain boundaries from 50 nautical miles (nm) to 200 nm, turbine hub heights of 100 m (previously 90 m), and a capacity array power density of 3 MW/km2(Walt Musial et al. 2016). A range of technology exclusions were applied based on maximum water depth for deployment, minimum wind speed, and limits to floating technology in freshwater surface ice. Resource potential was represented by more than 7,000 areas for offshore wind plant deployment after accounting for competing use and environmental exclusions, such as marine protected areas, shipping lanes, pipelines, and others.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

Based on a resource assessment (Walt Musial et al. 2016), LCOE was estimated at more than 7,000 areas (with a total capacity of approximately 2,000 GW). Using an updated version of NREL's Offshore Regional Cost Analyzer (ORCA) (Beiter et al. 2016), a variety of spatial parameters were considered, such as wind speeds, water depth, distance from shore, distance to ports, and wave height. CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor are calculated for each geographic location using engineering models, hourly wind resource profiles, and representative sea states. ORCA was calibrated to the latest cost and technology trends observed in the U.S. and European offshore wind markets, including:

- Turbine CAPEX: $1,300/kW were assumed for the Base Year to account for decreases in Turbine CAPEX that were observed in global offshore wind markets.

- Turbine Rating: A turbine technology trend of 6 MW (Base Year), 8 MW (2022 commercial operation date [COD]), 10 MW (2027 COD), and 10 MW (2032 COD) was assumed to correspond to recent technology trends. While higher turbine ratings may be commercially available during this period (e.g., up to 15-MW turbine ratings are expected to be commercially available by the early 2030s), the selected turbine ratings are intended to reflect the average turbine rating of the operating U.S. offshore wind fleet.

- Export System Cable Costs: A reduction of 25% in comparison to an earlier version of ORCA (Beiter et al. 2016) was assumed for the Base Year to account for increased competition within the supply chain in recent years and for changes in material use and commodity prices.

- Cost Reduction Trajectory: Recent literature was surveyed to identify the most up-to-date cost reduction trends expected for U.S. and European offshore wind projects; the version of ORCA used to estimate cost reduction trajectories are derived from Valpy et al. (2017)(fixed bottom) and Hundleby et al. (2017)(floating).

- Contingency Levels: A markup of 25% above of European contingency levels was assumed to account for the higher risk of installing and operating early offshore wind farms in the United States.

- Lease Area Price: This cost to projects was included to account for the recent increase in the tendered U.S. lease area prices.

The spatial LCOE assessment served as the basis for estimating the ATB baseline LCOE in the Base Year 2017, weighted by the available capacity, for fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind technology. Only sites that exceed a distance to cable landfall of 20 kilometers (km) and a water depth of 10 meters (m) were included in the spatial assessment for the ATB to represent those sites only that are likely to be developed in the near-to-medium term. Long-term average hourly wind profiles are assumed and estimated LCOE reflects the least-cost choice among four substructure types (Beiter et al. 2016):

- Monopile (fixed-bottom)

- Jacket (fixed-bottom)

- Semi-submersible (floating)

- Spar (floating).

The representative offshore wind plant size is assumed to be 600 MW (Beiter et al. 2016). For illustration in the ATB, the full resource potential, represented by 7,000 areas, was divided into 15 techno-resource groups (TRGs), of which TRGs 1-5 are representative of fixed-bottom wind technology and TRGs 6-15 are representative of floating offshore wind technology. The capacity-weighted average CAPEX, O&M, grid connection costs, and capacity factor for each group are presented in the ATB.

For illustration in the ATB, all potential offshore wind plant areas were represented in 15 TRGs with TRGs 1-5 representing fixed-bottom offshore technology and TRGs 6-15 representing floating offshore wind technology. These were defined by resource potential (GW) and have higher resolution on the least-cost TRGs, as these are the most likely sites to be deployed, based on their economics. The following table summarizes the capacity-weighted average water depth, distance to cable landfall, and cost and performance parameters for each TRG. The table includes the relative resource potential. Typical offshore wind installations in 2017 that have spatial and economic conditions that may lend themselves well to near-term deployment are associated with TRG 3.

TRG Definitions for Offshore Wind

| TRG | Weighted Water Depth (m) | Weighted Distance Site to Cable Landfall (km) | Weighted Average CAPEX ($/kW) | Weighted Average OPEX ($/kW/yr) | Weighted Average Net CF (%) | Potential Wind Plant Capacity of Fixed-Bottom/Floating Total (%) | |

| Fixed-Bottom | TRG 1 | 18 | 27 | 3,361 | 105 | 45 | 2 |

| TRG 2 | 22 | 29 | 3,475 | 106 | 44 | 3 | |

| TRG 3 | 24 | 33 | 3,660 | 109 | 44 | 7 | |

| TRG 4 | 29 | 57 | 4,001 | 112 | 41 | 44 | |

| TRG 5 | 31 | 65 | 4,633 | 107 | 30 | 44 | |

| Floating | TRG 6 | 144 | 38 | 4,602 | 77 | 52 | 1 |

| TRG 7 | 159 | 45 | 4,661 | 78 | 51 | 2 | |

| TRG 8 | 157 | 46 | 4,710 | 78 | 49 | 4 | |

| TRG 9 | 148 | 64 | 4,936 | 84 | 49 | 8 | |

| TRG 10 | 107 | 101 | 5,209 | 91 | 47 | 15 | |

| TRG 11 | 375 | 116 | 5,320 | 98 | 43 | 15 | |

| TRG 12 | 467 | 116 | 5,331 | 97 | 36 | 15 | |

| TRG 13 | 663 | 166 | 5,785 | 92 | 34 | 15 | |

| TRG 14 | 432 | 147 | 6,145 | 87 | 30 | 15 | |

| TRG 15 | 468 | 133 | 6,599 | 83 | 28 | 11 | |

Future year projections for CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor in the "Mid Technology Cost" Scenario are derived from the estimated cost reduction potential for offshore wind technologies based on assessments by BVG Associates ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) for 2017-2032. Based on the modeled data between 2017-2032, an (exponential) trend fit is derived for CAPEX, O&M in the "Mid Technology Cost" Scenario, and capacity factor to extrapolate ATB data for years 2033-2050. The specific scenarios are:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB.

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE percentage reduction estimated from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) from the Base Year, which is intended to correspond to a 50% probability of exceedance.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE deviation from the Mid Technology Cost Scenario in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050 informed by analysts' bottom-up technology and cost modeling. This scenario is intended to correspond to a 10%-30% probability of exceedance.

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

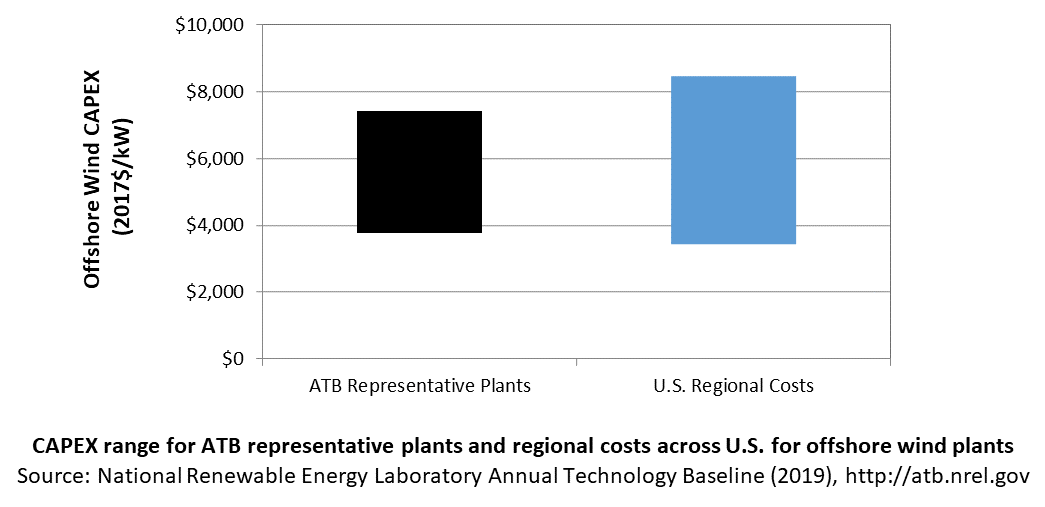

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the wind turbine, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with spatial site parameters in the contiguous United States.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

Based on Moné at al. (2015) and Beiter et al. (2016), the System Cost Breakdown Structure of the ATB for the wind plant envelope is defined to include:

- Wind turbine supply

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Turbine installation, substructure supply and installation

- Site preparation, port and staging area support for delivery, storage, handling, and installation of underground utilities

- Electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting turbines to each other (array cable system costs) and to the cable landfall (export cable system costs)

- Development and project management

- Financial costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Interest during construction estimated based on three-year duration accumulated 40%/40%/20% at half-year intervals and an 8% interest rate (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor). Because transmission infrastructure between an offshore wind plant and the point at which a grid connection is made onshore is a significant component of the offshore wind plant cost, an offshore spur line cost (OffSpurCost) for each TRG is included in the CAPEX estimate. The offshore spur line cost reflects a capacity-weighted average of all potential wind plant areas within a TRG, similar to OCC.

In the ATB, CAPEX represents the capacity-weighted average values of all potential wind plant areas within a TRG and varies with water depth and distance from shore. Regional cost effects associated with labor rates, material costs, and other regional effects as defined by DOE and NREL (2015) expand the range of CAPEX. Unique land-based spur line costs for each of the 7,000 areas based on distance and transmission line costs expand the range of CAPEX even further. The following figure illustrates the ATB representative plants relative to the range of CAPEX including regional costs across the contiguous United States. The ATB representative plants are associated with a regional multiplier of 1.0.

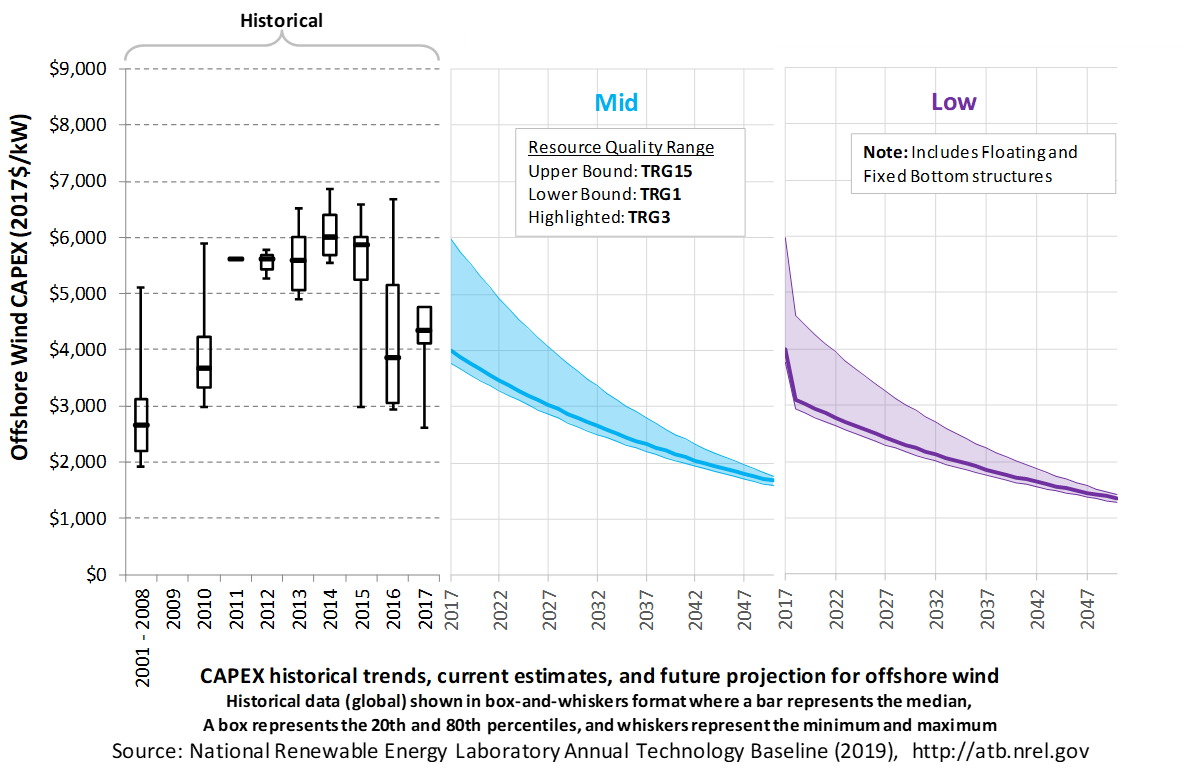

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs. Mid and Low technology cost scenarios are shown. Historical data from offshore wind plants installed globally are shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Recent Trends

Actual global offshore wind plant CAPEX is shown in box-and-whiskers format for comparison to the ATB current CAPEX estimates and future projections. CAPEX estimates for 2017 correspond well with market data for plants installed in 2017. Projections reflect a continuation of the downward trend observed in the recent past and are anticipated to continue based on preliminary data for 2017 projects.

Base Year Estimates

Base Year estimates for CAPEX were derived using an updated version of NREL's Offshore Regional Cost Analyzer (ORCA) (Beiter et al. 2016). A variety of spatial parameters were considered, such as water depth, distance from shore, distance to ports, and wave height to estimate CAPEX. CAPEX estimates were calibrated to correspond to the latest cost and technology trends observed in the U.S. and European offshore wind markets, including:

- Turbine CAPEX: $1,300/kW were assumed for the Base Year to account for decreases in Turbine CAPEX that were observed in global offshore wind markets.

- Turbine Rating: A turbine technology trend of 6 MW (Base Year), 8 MW (2022 commercial operation date [COD]), 10 MW (2027 COD), and 10 MW (2032 COD) was assumed to correspond to recent technology trends. While higher turbine ratings may be commercially available during this period (e.g., up to 15-MW turbine ratings are expected to be commercially available by the early 2030s), the selected turbine ratings are intended to reflect the average turbine rating of the operating U.S. offshore wind fleet.

- Export System Cable Costs: A reduction of 25% in comparison to an earlier version of ORCA (Beiter et al. 2016) was assumed for the Base Year to account for increased competition within the supply chain in recent years and for changes in material use and commodity prices.

- Cost Reduction Trajectory: Recent literature was surveyed to identify the most up-to-date cost reduction trends expected for U.S. and European offshore wind projects; the version of ORCA used to estimate cost reduction trajectories are derived from Valpy et al. (2017)(fixed bottom) and Hundleby et al. (2017) (floating).

- Contingency Levels: A markup of 25% on top of European contingency levels was assumed to account for the higher risk of installing and operating early offshore wind farms in the United States.

- Lease Area Price: This cost to projects was included to account for the recent increase in the tendered U.S. lease area prices.

Future Year Projections

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX percentage reduction estimated from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017) for fixed-bottom and (Hundleby et al. 2017)) from the Base Year, which is intended to correspond to a 50% probability of exceedance.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX deviation from the Mid Technology Cost Scenario in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050 informed by analysts' bottom-up technology and cost modeling. This scenario is intended to correspond to a 10%-30% probability of exceedance.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., but the ReEDS model does include 134 regional multipliers (EIA 2013).

The ReEDS model determines offshore spur line and land-based spur line (GCC) uniquely for each of the 7,000 areas based on distance and transmission line cost.

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent the annual fixed expenditures required to operate and maintain a wind plant over its lifetime, including:

- Insurance, taxes, land lease payments and other fixed costs (e.g., project management and administration, weather forecasting, and condition monitoring)

- Present value and annualized large component replacement costs over technical life (e.g., blades, gearboxes, and generators)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of wind plant components, including turbines and transformers, over the technical lifetime of the plant.

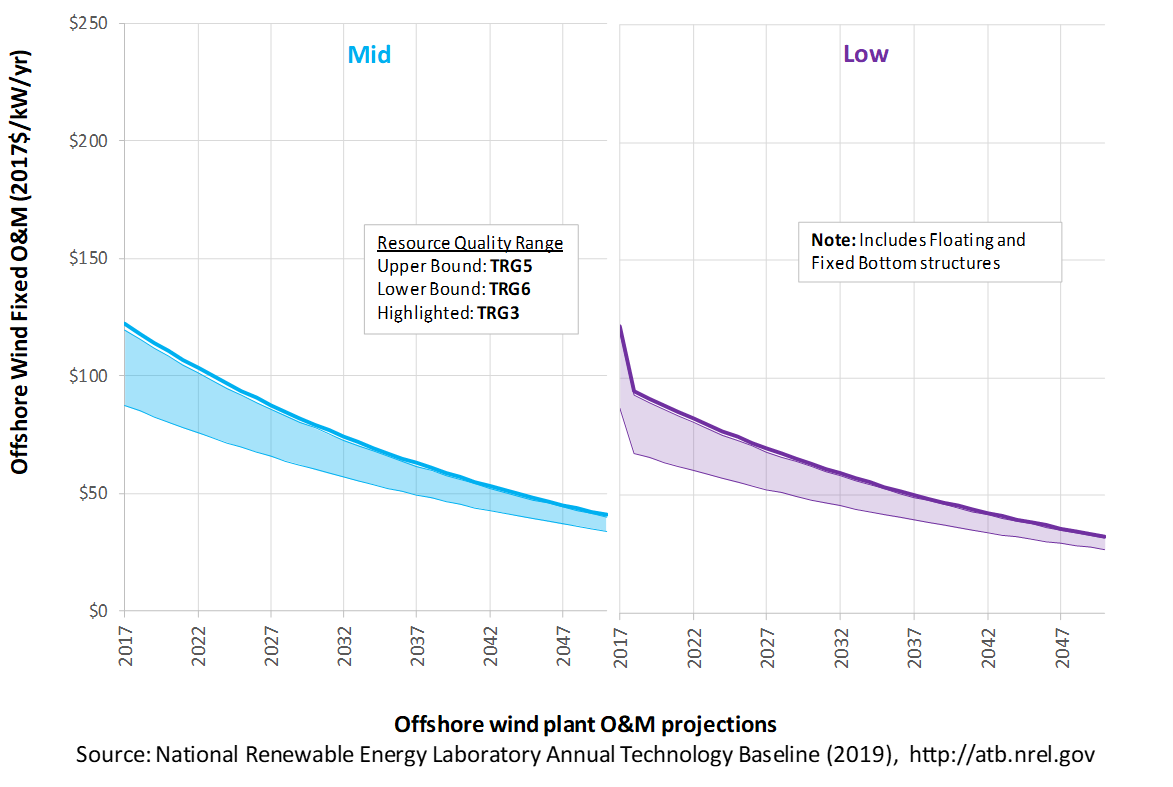

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed and floating O&M (FOM) costs. Mid and Low technology cost scenarios are shown. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year. The range of Base Year O&M estimates reflect the variation in spatial parameters such as distance from shore and metocean conditions.

Base Year Estimates

FOM costs vary by distance from shore and metocean conditions. As a result, O&M costs in the "Mid Technology Cost Scenario" vary from $87/kW-year (TRG 6) to $127/kW-year (TRG 4) in 2017. The average in the ATB "Mid Technology Cost Scenario" for fixed-bottom offshore technology (TRGs 1-5) is $121/kW-year; the corresponding value for floating offshore wind technology (TRGs 6-15) is $97/kW-year.

Future Year Projections

Future fixed-bottom offshore wind technology O&M is estimated to decline 66% by 2050 in the Mid cost case.

Future floating offshore wind technology O&M is estimated to decline 61% by 2050 in the Mid cost case.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

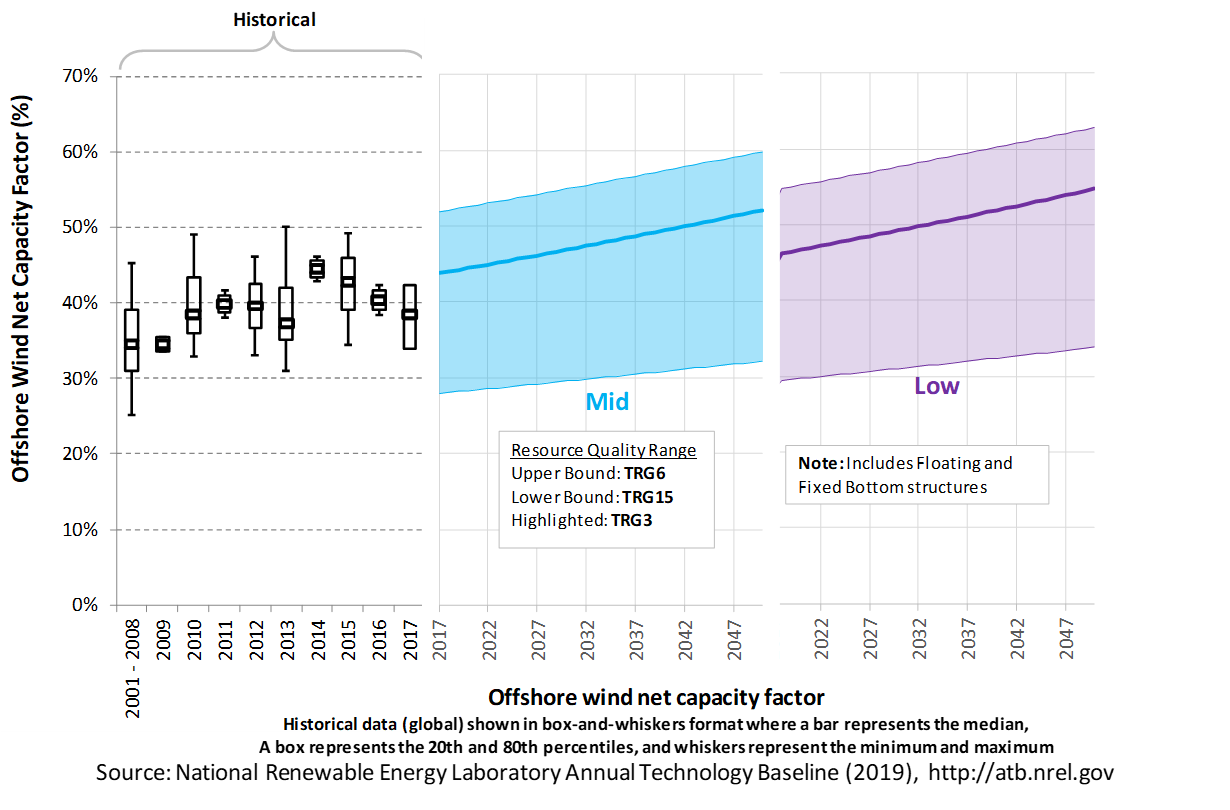

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

The capacity factor is influenced by the rotor swept area/generator capacity, hub height, hourly wind profile, expected downtime, and energy losses within the wind plant. It is referenced to 100-m above-water-surface, long-term average hourly wind resource data from Musial et al. (2016).

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in the wind resource for offshore wind plants in the contiguous United States. Preconstruction estimates for offshore wind plants operating globally in 2015, according to the year in which plants were installed, is shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The range of Base Year estimates illustrates the effect of locating an offshore wind plant in a variety of wind resource (TRGs 1-5 are fixed-bottom offshore wind plants and TRGs 6-15 are floating offshore wind plants). Future projections are shown for Mid and Low technology cost scenarios.

Recent Trends

Preconstruction annual energy estimates from publicly available global operating wind capacity in 2017 (Walter Musial et al. forthcoming) are shown in a box-and-whiskers format for comparison with the ATB current estimates and future projections. The historical data illustrate preconstruction estimated capacity factors for projects by year of commercial online date. The figure shows the comparison between the range of capacity factors defined by the ATB TRGs and the reported capacity factors for projects installed in 2017.

Base Year Estimates

The capacity factor is determined using a representative power curve for a generic NREL-modeled 6-MW offshore wind turbine (Beiter et al. 2016) and includes geospatial estimates of gross capacity factors for the entire resource area (Walt Musial et al. 2016). The net capacity factor considers spatial variation in wake losses, electrical losses, turbine availability, and other system losses. For illustration in the ATB, all 7,000 wind plant areas are represented in 15 TRGs.

Future Year Projections

Projections of capacity factors for plants installed in future years were determined based on estimates obtained from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) for both fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind technologies. Projections for capacity factors implicitly reflect technology innovations such as larger rotors and taller towers that will increase energy capture at the same geographic location without explicitly specifying tower height and rotor diameter changes.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model output capacity factors for offshore wind can be lower than input capacity factors due to endogenously estimated curtailments determined by scenario constraints.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

ATB projections between the Base Year and 2032 (COD) were derived from an expert elicitation conducted by BVG Associates ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)). The expert elicitation assesses the impact of more than 50 technology innovations on various cost components of European offshore wind farms up to 2032 (COD). The cost impact from technology innovations was assessed by soliciting industry experts about the maximum cost impact from a technology innovation in combination with an assessment of an innovation's commercial readiness and market share in a given year.

For the ATB, three different technology cost scenarios were adapted from the expert survey results for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB.

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE percentage reduction estimated from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) from the Base Year, intended to correspond to a 50% probability of exceedance.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE deviation from the Mid Technology Cost Scenario in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050 informed by analysts' bottom-up technology and cost modeling. This scenario is intended to correspond to a 10%-30% probability of exceedance.

Expert survey estimates from BVG Associates were normalized to the ATB Base Year starting point and applied to overnight capital costs (OCC), FOM, and annual energy production in 2022 (COD), 2027 (COD), and 2032 (COD). These serve as the ATB Mid projection between 2017-2032 (COD). The ATB Mid scenario is intended to represent a cluster of technology innovations that change the manufacturing, installation, operation, and performance of a wind farm consistent with historical cost reduction rates. The ATB Low scenario is intended to represent a cluster of technology innovations that fundamentally change the manufacturing, installation, operation and performance of a wind farm resulting in considerably higher cost reductions than the ATB Mid scenario. The ATB Low scenario is represented by cost reductions that are twice the rate achieved in the ATB Mid scenario. The percentage reduction in LCOE was applied equally across all TRGs. The cost reductions for ATB Mid and ATB Low scenarios between 2032 and 2050 were extrapolated (i.e., exponentially fit) based on the estimated trend between 2017 and 2032 (COD).

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a summary metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

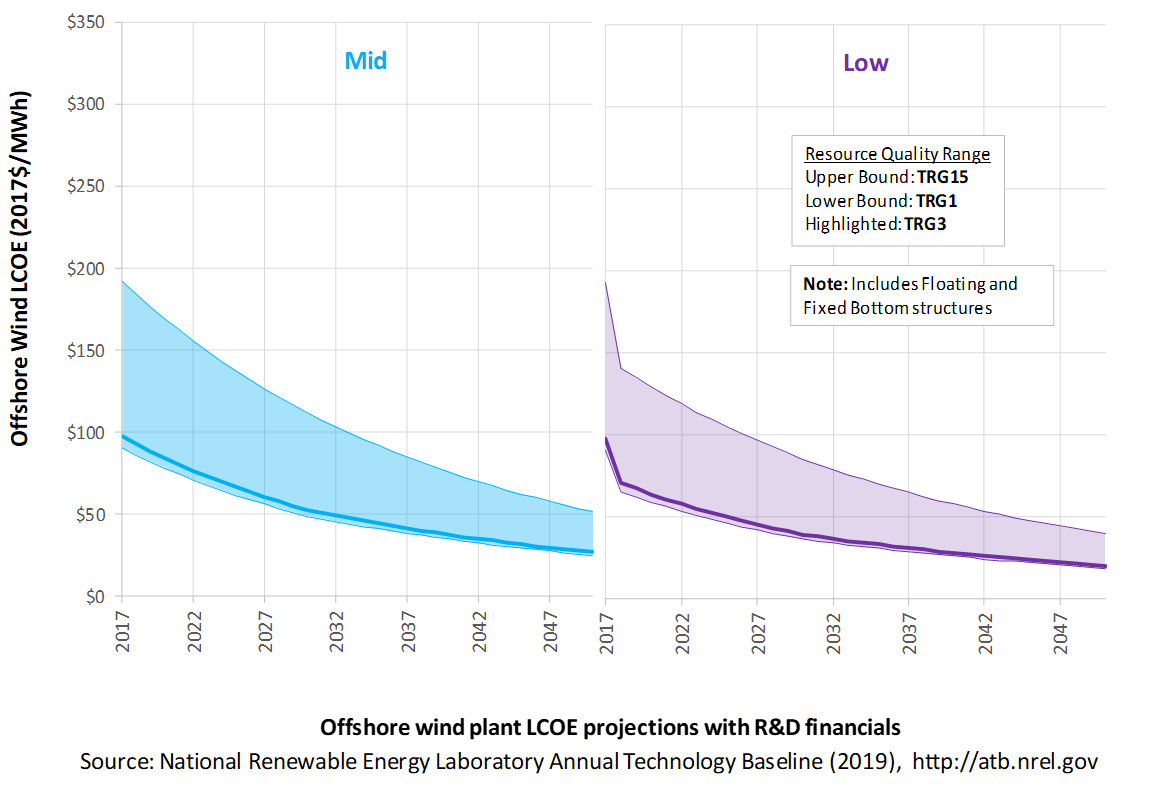

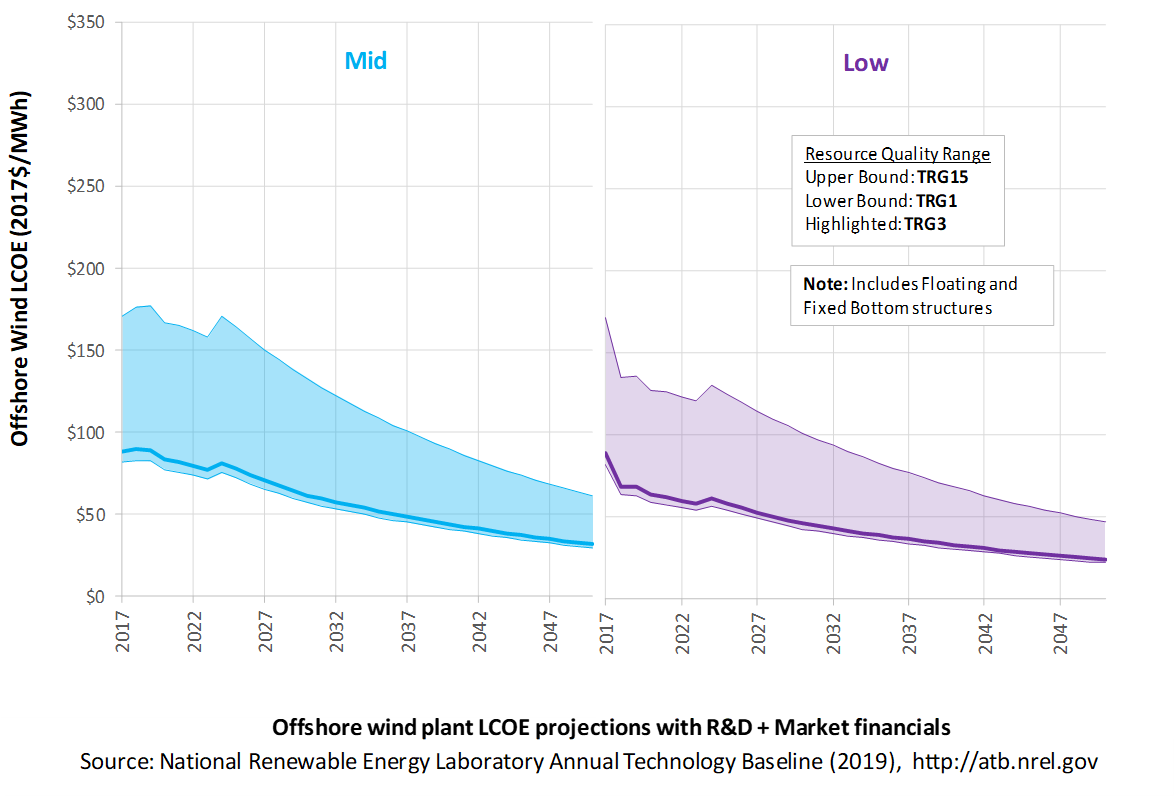

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for offshore wind across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform and tax credits. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term offshore wind plants are associated with TRG 3. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA 2019) and excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2019 (EIA 2019) as well as effects of tax reform and tax credits. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE.

A constant cost recovery period-over which the initial capital investment is recovered-of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below:

- The financing conditions assumed for the ATB are applicable to commercial-scale offshore wind projects only. Commercial-scale fixed-bottom offshore wind projects are expected to be installed starting in the early 2020s (Walter Musial et al. forthcoming). Offshore wind projects using floating technology are in a pre-commercial phase currently (i.e., multi-turbine arrays between 12-50 MW in size) for which the ATB financial assumptions are likely too favorable. Once floating technology is deployed at commercial scale, the ATB financial assumptions are expected to appropriately reflect the terms of financing. The use of floating technology for commercial-scale projects is expected by the mid-2020s. Continued turbine scaling to larger-megawatt turbines with larger rotors such that swept area/megawatt capacity decreases resulting in higher capacity factors for a given location

- Greater market competition in the production of primary components (e.g., turbines, support structure), and installation services

- Economy-of-scale and productivity improvements in manufacturing, including mass production of substructure component and optimized installation strategies

- Improved plant siting and operation to reduce plant-level energy losses, resulting in higher capacity factors

- More efficient O&M procedures combined with more reliable components to reduce annual average FOM costs

- Adoption of a wide range of innovative control, design, and material concepts that facilitate the high-level trends described above.

Geothermal

Geothermal technology cost and performance projections have been updated with analysis and results from the GeoVision: Harnessing the Heat Beneath our Feet report (DOE, 2019). The GeoVision report is a collaborative multiyear effort with contributors from industry, academia, national laboratories, and federal agencies. The analysis in the report updates resource potential estimates as well as current and projected capital and O&M costs based on rigorous, bottom-up modeling.

Representative Technology

Hydrothermal geothermal technologies encompass technologies for exploring for the resource, drilling to access the resource, and building power plants to convert geothermal energy to electricity. Technology costs depend heavily on the hydrothermal resource temperature and well productivity and depth, so much so that project costs are site-specific and applying a "typical" cost to any given site would be inaccurate. The 2019 ATB uses scenarios developed by the DOE Geothermal Technology Office (Mines, 2013) for representative binary and flash hydrothermal power plant technologies. The first scenario assumes a 175°C resource at a depth of 1.5 km with wells producing an average of 110 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 30-MWe binary (organic Rankine cycle) power plant. The second scenario assumes a 225°C resource at a depth of 2.5 km with wells producing 80 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 40-MWe dual-flash plant. These are mid-grade or "typical" temperatures and depths for binary and flash hydrothermal projects. The ReEDS model uses the full hydrothermal supply curve. The 2019 ATB representative technologies fall in the middle or near the end of the hydrothermal resources typically deployed in ReEDS model runs.

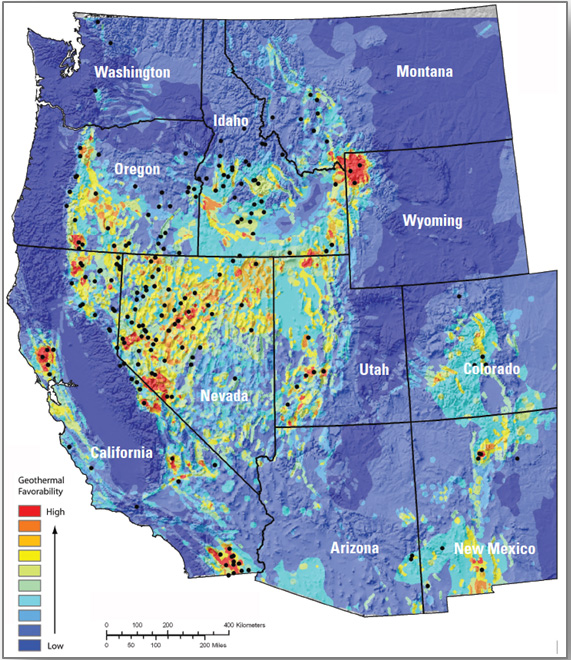

Resource Potential

The hydrothermal geothermal resource is concentrated in the western United States. The total mean potential is 39,090 MW: 9,057 MW identified and 30,033 MW undiscovered (USGS, 2008). The resource potential identified by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, 2008) at each site is based on available reservoir thermal energy information from studies conducted at the site. The undiscovered hydrothermal technical potential estimate is based on a series of GIS statistical models for the spatial correlation of geological factors that facilitate the formation of geothermal systems.

The U.S. Geological Survey resource potential estimates for hydrothermal were used with the following modifications:

- Installed capacity of about 3 GW in 2016 is excluded from the resource potential.

- Resources on federally protected and U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) lands, where development is highly restricted are excluded from the resource potential, as are resources on lands where significant barriers that prevent or inhibit development of geothermal projects were identified by Augustine, Ho, and Blair (2019).

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012), represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential-resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

The Base Year cost and performance estimates are calculated using Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model (GETEM), a bottom-up cost analysis tool that accounts for each phase of development of a geothermal plant (DOE "Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model").

- Cost and performance data for hydrothermal generation plants are estimated for each potential site using GETEM. Model results are based on resource attributes (e.g., estimated reservoir temperature, depth, and potential) of each site. GETEM inputs are derived from the Business-as-Usual (BAU) scenario from GeoVision ( (DOE, 2019), (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)).

- Site attribute values are from (USGS, 2008) for identified resource potential and from capacity-weighted averages of site attribute values of nearby identified resources for undiscovered resource potential.

- GETEM is used to estimate CAPEX, O&M, and parasitic plant losses that affect net energy production.

Capacity factor and O&M costs for plants installed in future years are unchanged from the Base Year. Projections for hydrothermal and EGS technologies are equivalent.

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX cost reduction based on assumed minimum learning as implemented in AEO (EIA, 2015): 10% by 2035; this corresponds to a 0.5% annual improvement in CAPEX, which is assumed to continue on through 2050

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX based on the Technology Improvement scenario from GeoVision Study ( (DOE, 2019); (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)); cost and technology improvements change linearly from present values and are fully achieved by 2030.

Representative Technology

As with cost for projects that use hydrothermal resources, EGS resource project costs depend so heavily on the hydrothermal resource temperature and well productivity and depth that project costs are site-specific. The 2019 ATB uses scenarios developed by the DOE Geothermal Technology Office (Mines, 2013) for representative binary and flash EGS power plants assuming current (immature) EGS technology performance metrics. The first scenario assumes a 175°C resource at a depth of 3 km with wells producing an average of 40 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 25-MWe binary (organic Rankine cycle) power plant. The second scenario assumes a 250°C resource at a depth of 3.5 km with wells producing 40 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 30-MWe dual-flash plant. These temperatures and depths are at the low-cost end of the EGS supply curve and would be some of the first developed. The ReEDS model uses the full EGS supply curve. Neither of these technologies is typically used.

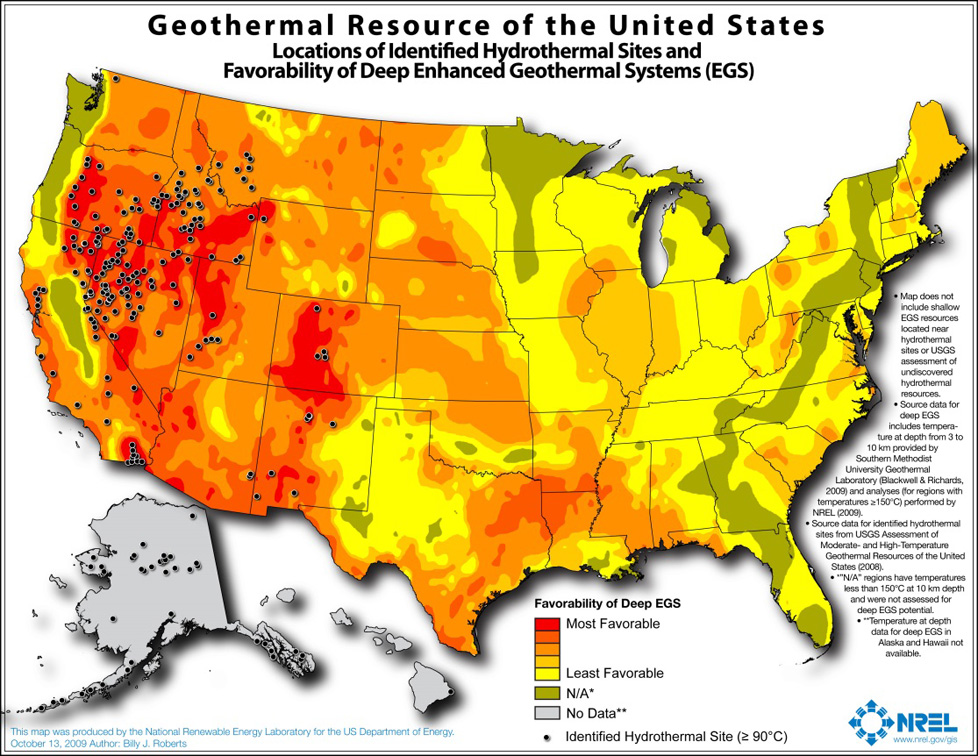

Resource Potential

The enhanced geothermal system (EGS) resource is concentrated in the western United States. The total potential is greater than 100,000 MW: 1,493 MW of near-hydrothermal field EGS (NF-EGS) and the remaining potential comes from deep EGS.

Renewable energy technical potential as defined by Lopez et al. (2012) represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, environmental, and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand there are multiple types of potential-resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

The Base Year cost and performance estimates are calculated using the Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model (GETEM), a bottom-up cost analysis tool that accounts for each phase of development of a geothermal plant (DOE "Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model").

- Cost and performance data for EGS generation plants are estimated for each potential site using GETEM. Model results based on resource attributes (e.g., estimated reservoir temperature, depth, and potential) of each site. GETEM inputs are derived from the GeoVision BAU scenario ( (DOE, 2019), (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)).

- Approaches to restrict resource potential to about 500 GW based on USGS analysis may be implemented in the future.

- GETEM is used to estimate CAPEX and O&M and parasitic plant losses that affect net energy production.

Capacity factor and O&M costs for plants installed in future years are unchanged from the Base Year. Projections for hydrothermal and enhanced geothermal system technologies are equivalent.

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050, consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX cost reduction based on assumed minimum learning as implemented in AEO (EIA, 2015): 10% by 2035; this corresponds to a 0.5% annual improvement in CAPEX, which is assumed to continue on through 2050.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX based on the GeoVision Technology Improvement scenario ( (DOE, 2019), (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)). Cost and technology improvements decrease linearly from present values and are fully achieved by 2030.

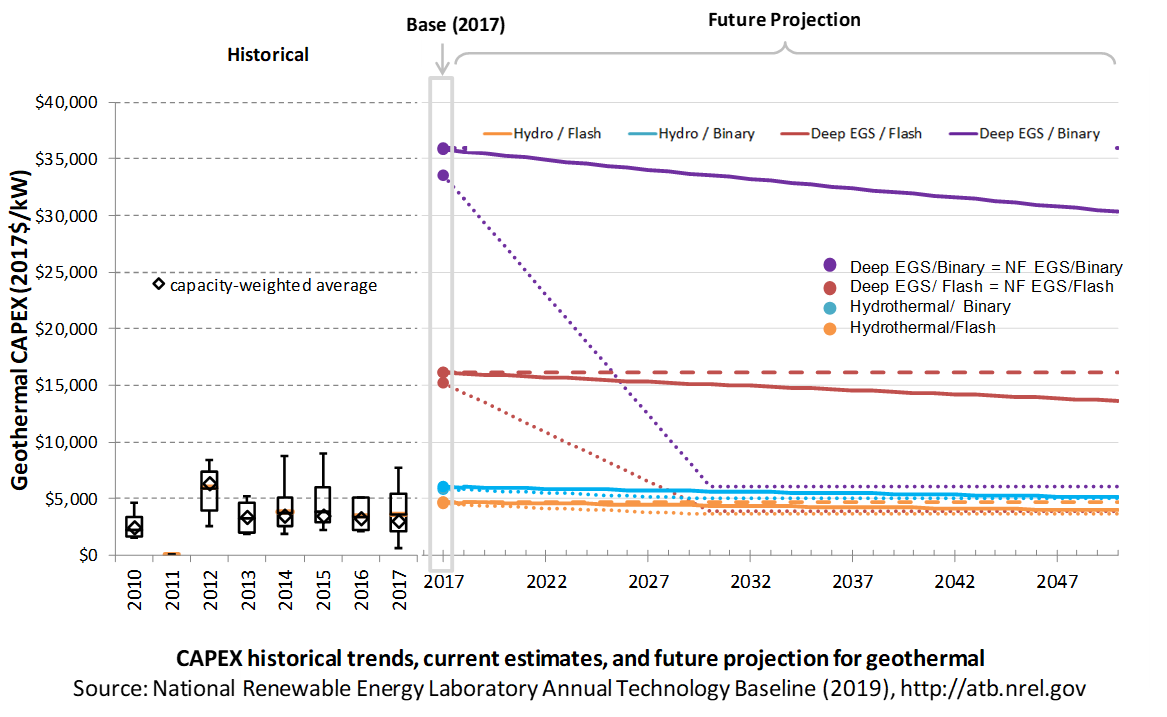

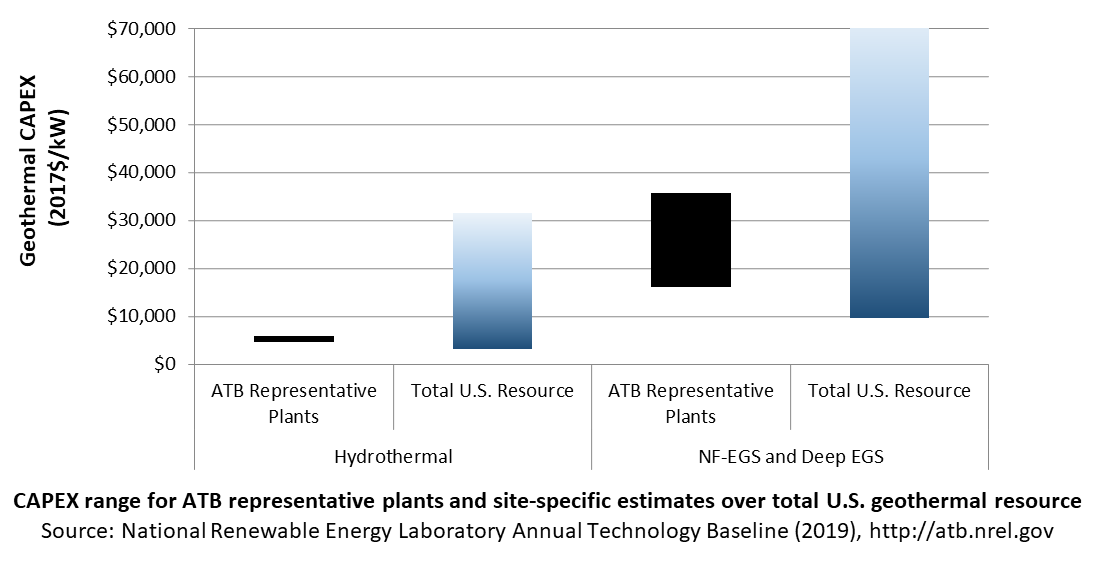

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the geothermal generation plant, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with resource in the contiguous United States.

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs. Three cost scenarios are represented: Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, six representative geothermal plants are shown. Two energy conversion processes are common: binary organic Rankine cycle and flash.

- Binary plants use a heat exchanger to transfer geothermal energy to an organic Rankine cycle. This technology generally applies to lower-temperature systems. These systems have higher CAPEX than flash systems because of the increased number of components, their lower-temperature operation, and a general requirement that a number of wells be drilled for a given power output.

- Flash plants create steam directly from the thermal fluid through a pressure change. This technology generally applies to higher-temperature systems. Due to the reduced number of components and higher-temperature operation, these systems generally produce more power per well, thus reducing drilling costs. These systems generally have lower CAPEX than binary systems.

Examples using each of these plant types in each of the three resource types (hydrothermal, NF-EGS, and deep EGS) are shown in the ATB.

Costs are for new or greenfield hydrothermal projects, not for re-drilling or additional development/capacity additions at an existing site.

Characteristics for the six examples of plants representing current technology were developed based on discussion with industry stakeholders. The CAPEX estimates were generated using GETEM. CAPEX for NF-EGS and EGS are equivalent.

The following table shows the range of OCC associated with the resource characteristics for potential sites throughout the United States.

| Temp (°C) | >=200C | 150-200 | 135-150 | <135 | |

| Hydrothermal | Number of identified sites | 21 | 23 | 17 | 59 |

| Total capacity (MW) | 15,338 | 2,991 | 820 | 4,632 | |

| Average OCC ($/kW) | 3,906 | 7,720 | 8,794 | 16,248 | |

| Min OCC ($/kW) | 3,000 | 4,140 | 7,004 | 10,950 | |

| Max OCC ($/kW) | 5,491 | 29,135 | 11,027 | 21,349 | |

| Example of plant OCC ($/kW) | 4,229 | 5,455 | |||

| NF-EGS | Number of sites | 12 | 20 | ||

| Total capacity (MW) | 787 | 596 | |||

| Average OCC ($/kW) | 11,041 | 26,077 | |||

| Min OCC ($/kW) | 8,778 | 18,172 | |||

| Max OCC ($/kW) | 18,009 | 39,987 | |||

| Example of plant OCC ($/kW) | 14,512 | 32,268 | |||

| Deep EGS (3-6 km) | Number of sites | n/a | n/a | ||

| Total capacity (MW) | 100,000+ | ||||

| Average OCC ($/kW) | 28,418 | 60,170 | |||

| Min OCC ($/kW) | 18,320 | 39,329 | |||

| Max OCC ($/kW) | 54,047 | 77,983 | |||

| Example of plant OCC ($/kW) | 14,512 | 32,268 | |||

Future Year Projections

Projection of future geothermal plant CAPEX for the Low case is based on the GeoVision Technology Improvement scenario (DOE, 2019).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

For the ATB – and based on (EIA, 2016) and GETEM component cost calculations – the geothermal plant envelope is defined to include:

- Geothermal generation plant

- Exploration, confirmation drilling, well field development, reservoir stimulation (EGS), plant equipment, and plant construction

- Power plant equipment, well-field equipment, and components for wells (including dry/non-commercial wells)

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Installation and electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting turbines to each other and to the control center

- Project indirect costs, including costs related to engineering, distributable labor and materials, construction management start up and commissioning, and contractor overhead costs, fees, and profit

- Financial costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Electrical interconnection and onsite electrical equipment (e.g., switchyard), a nominal-distance spur line (<1 mile), and necessary upgrades at a transmission substation; distance-based spur line cost (GCC) not included in the ATB

- Interest during construction estimated based on four-year and five-year duration for hydrothermal and EGS respectively (for the low scenario) and an eight-year duration and ten-year duration for hydrothermal and EGS respectively (for the mid- and constant-scenario) accumulated at different intervals for hydro and EGS based on scheduled at outlined by the GeoVision Study (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

In the ATB, CAPEX is shown for six representative plants. Examples of CAPEX for binary organic Rankine cycle and flash energy conversion processes in each of three geothermal resource types are presented. CAPEX estimates for all hydrothermal NF-EGS potential results in a CAPEX range that is much broader than that shown in the ATB. It is unlikely that all the resource potential will be developed due to the high costs for some sites. Regional cost effects and distance-based spur line costs are not estimated.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model represents cost and performance for hydrothermal, NF-EGS, and EGS potential in 5 bins for each of 134 geographic regions, resulting in a greater CAPEX range in the reference supply curve than what is shown in examples in the ATB.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., and neither does the ReEDS model.

CAPEX in the ATB does not include geographically determined spur line (GCC) from plant to transmission grid, and neither does the ReEDS model.

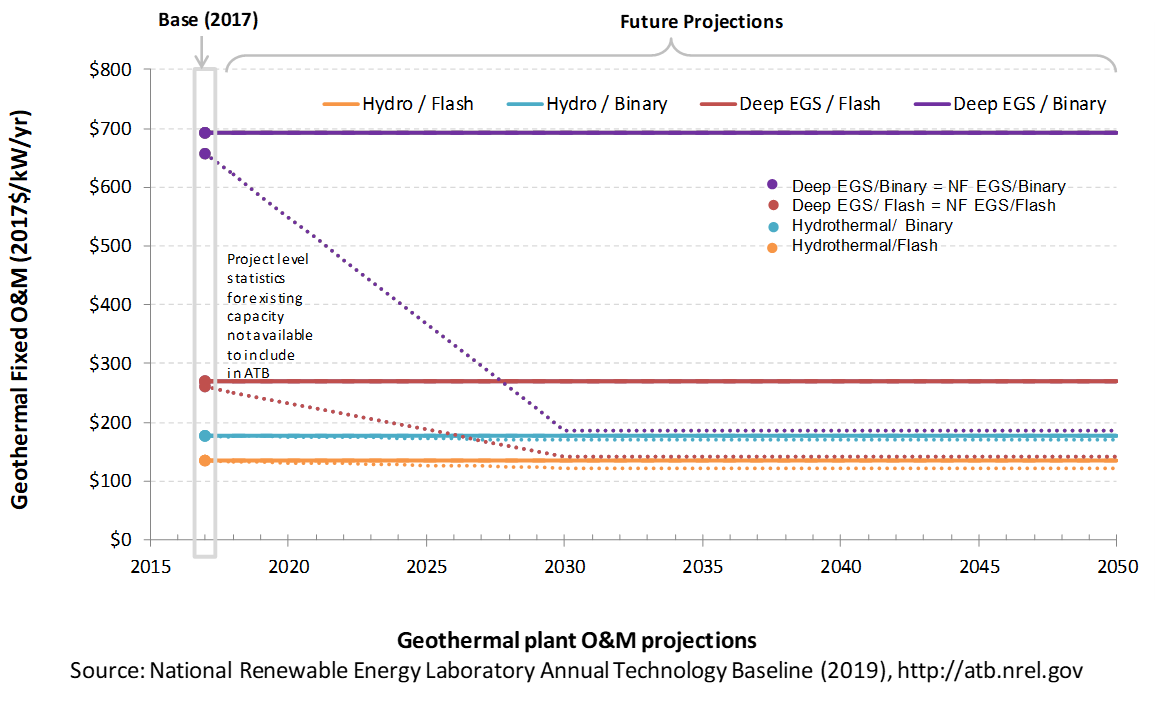

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent average annual fixed expenditures (and depend on rated capacity) required to operate and maintain a hydrothermal plant over its lifetime of 30 years (plant and reservoir), including:

- Insurance, taxes, land lease payments, and other fixed costs

- Present value and annualized large component overhaul or replacement costs over technical life (e.g., downhole pumps)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of geothermal plant components and well field components over the technical lifetime of the plant and reservoir.

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed O&M (FOM) costs. Three cost scenarios are represented. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

FOM is estimated for each example of a plant based on technical characteristics.

GETEM is used to estimate FOM for each of the six representative plants. FOM for NF-EGS and EGS are equivalent.

Future Year Projections

Future FOM cost reductions are based on results from the GeoVision scenario (DOE, 2019) and are described in detail in Augustine, Ho, and Blair (2019).

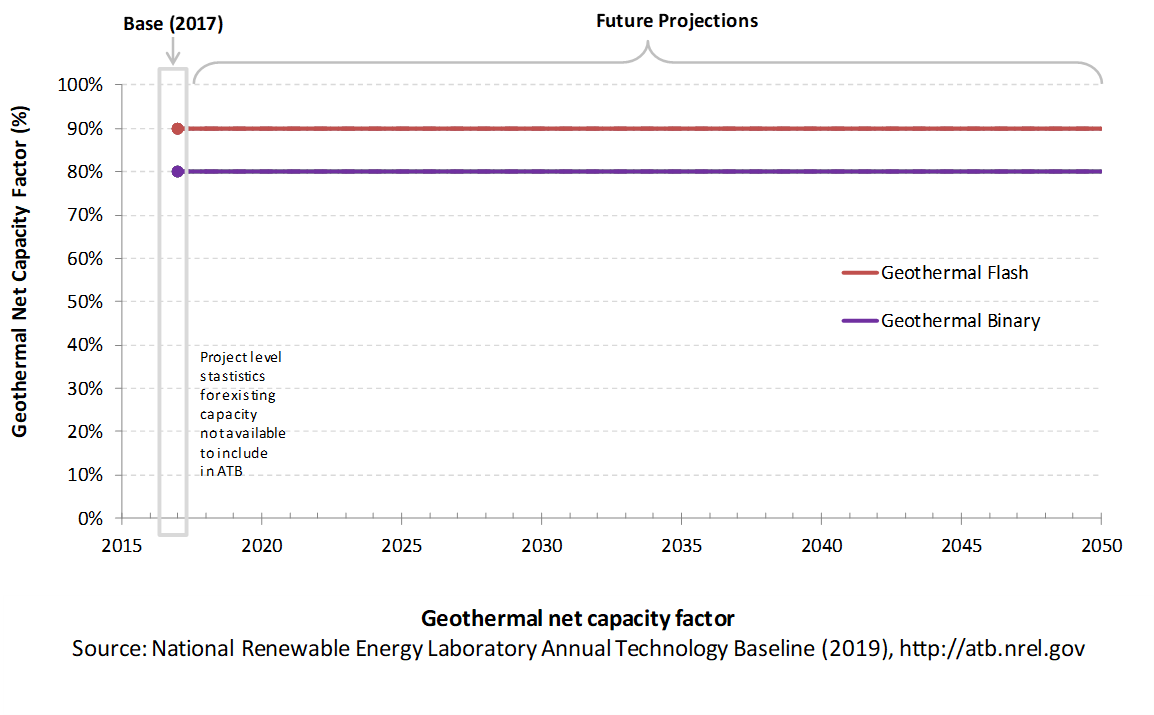

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the technical lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

Geothermal plant capacity factor is influenced by diurnal and seasonal air temperature variation (for air-cooled plants), technology (e.g., binary or flash), downtime, and internal plant energy losses.

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in the resource for plants in the contiguous United States. The range of the Base Year estimates illustrates Binary or Flash geothermal plants. Future year projections for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are unchanged from the Base Year. Technology improvements are focused on CAPEX cost elements.

Base Year Estimate

The capacity factor estimates are developed using GETEM at typical design air temperature and based on design plant capacity net losses. An additional reduction is applied to approximate potential variability due to seasonal temperature effects.

Some geothermal plants have experienced year-on-year reductions in energy production, but this is not consistent across all plants. No approximation of long-term degradation of energy output is assumed.

Ongoing work at NREL and the Idaho National Laboratory is helping improve capacity factor estimates for geothermal plants. As this work progresses, it will be incorporated into future versions of the ATB.

Future Year Projections

Capacity factors remain unchanged from the Base Year through 2050. Technology improvements are focused on CAPEX costs. Estimates of capacity factor for geothermal plants in the ATB represent typical operation. The dispatch characteristics of these systems are valuable to the electric system to manage changes in net electricity demand. Actual capacity factors will be influenced by the degree to which system operators call on geothermal plants to manage grid services.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

The site-specific nature of geothermal plant cost, the relative maturity of hydrothermal plant technology, and the very early stage development of EGS technologies make cost projections difficult. No thorough literature reviews have been conducted for cost reduction of hydrothermal geothermal technologies or EGS technologies. However, the GeoVision BAU scenario is based on a bottom-up analysis of costs and performance improvements. The inputs for the BAU scenario were developed by the national laboratories as part of the GeoVision effort, and it was reviewed by industry experts.

Projection of future geothermal plant CAPEX for the Low cost case is based on the GeoVision Technology Improvement scenario. It assumes that cost and technology improvements are achieved by 2030 and that costs decrease linearly from present values to the 2030 projected values. The Mid cost case is based on minimum learning rates as implemented in AEO (EIA, 2015): 10% by 2035. This corresponds to a 0.5% annual improvement in CAPEX, which is assumed to continue on through 2050. The Constant technology cost scenario retains all cost and performance assumptions equivalent to the Base Year through 2050.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a simple metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies such as geothermal, can provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

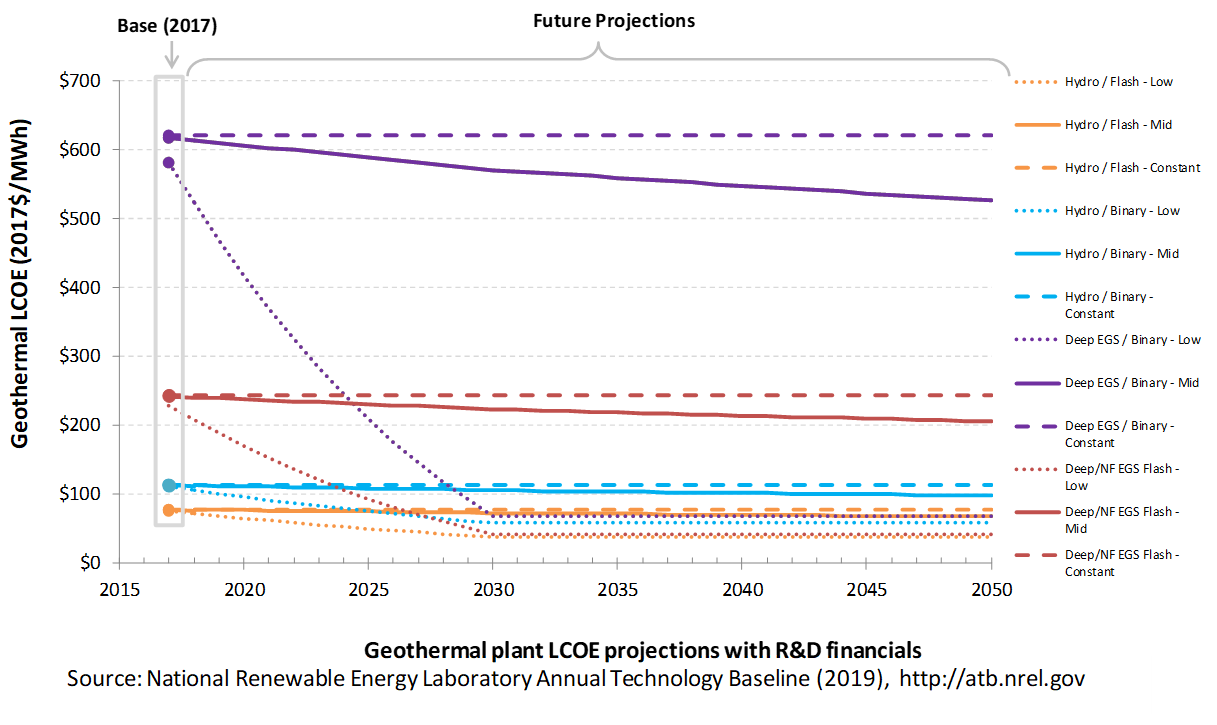

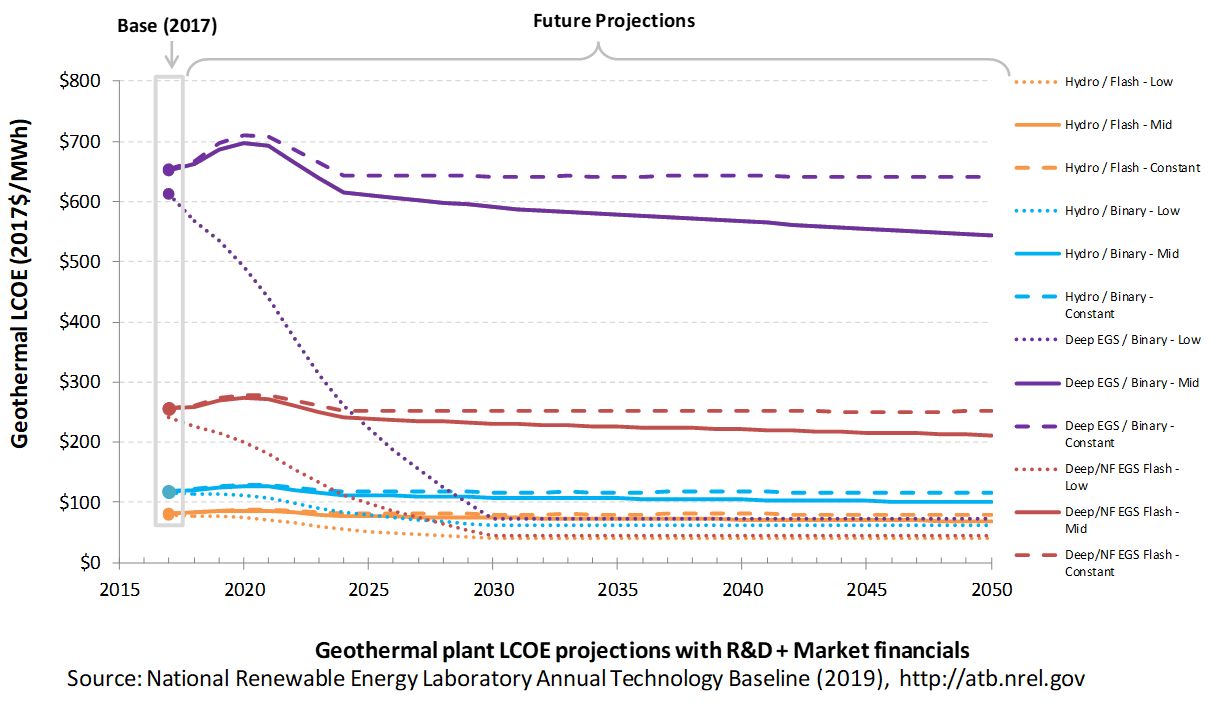

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for geothermal across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs but not in the upfront capital costs (e.g., developer fees and contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside the United States, due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g., offshore wind in Europe) or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, technology-specific tariffs, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term geothermal plants are associated with Hydrothermal/Flash. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA, 2019) and excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2018, as well as effects of tax reform, tax credits, and technology-specific tariffs. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Changes from 2018 ATB to 2019 ATB.

A constant cost recovery period – over which the initial capital investment is recovered – of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below.

- Development of exploration and reservoir characterization tools that reduce well-field costs through risk reduction by locating and characterizing low- and moderate-temperature hydrothermal systems prior to drilling

- High-temperature tools and electronics for geothermal subsurface operations

- Development of reservoir engineering techniques and technologies that enable EGS

- More efficient drilling practices and advanced drilling systems such as using flames or lasers to drill through rock; drilling steering technology; and other technologies to reduce drilling costs.

References

The following references are specific to this page; for all references in this ATB, see References.Augustine, Chad, Ho, J., & Blair, N. (2019). GeoVision Analysis Supporting Task Force Report: Electric Sector Potential to Penetration (No. NREL/ TP-6A20-71833). Retrieved from National Renewable Energy Laboratory website: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/71833.pdf

Augustine, Chad. (2016). Updates to Enhanced Geothermal System Resource Potential Estimate. GRC Transactions, 40, 673–677. Retrieved from http://pubs.geothermal-library.org/lib/grc/1032382.pdf

Beiter, P., Musial, W., Smith, A., Kilcher, L., Damiani, R., Maness, M., … Scott, G. (2016). A Spatial-Economic Cost-Reduction Pathway Analysis for U.S. Offshore Wind Energy Development from 2015-2030 (Technical Report No. NREL/TP-6A20-66579). https://doi.org/10.2172/1324526

DOE, & NREL. (2015). Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States (Technical Report No. DOE/GO-102015-4557). Retrieved from U.S. Department of Energy website: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/63197-2.pdf

DOE. (2019). GeoVision: Harnessing the Heat Beneath Our Feet (No. DOE/EE-1306). Retrieved from U.S. Department of Energy website: https://www.energy.gov/eere/geothermal/geovision

EIA. (2013). Updated Capital Cost Estimates for Utility Scale Electricity Generating Plants. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration website: https://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/powerplants/capitalcost/archive/2013/pdf/updated_capcost.pdf

EIA. (2015). Annual Energy Outlook 2015 with Projections to 2040 (No. AEO2015). Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration website: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/0383(2015).pdf

EIA. (2016b). Capital Cost Estimates for Utility Scale Electricity Generating Plants. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration website: https://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/powerplants/capitalcost/pdf/capcost_assumption.pdf

EIA. (2019a). Annual Energy Outlook 2019 with Projections to 2050. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration website: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/AEO2019.pdf

Hundleby, G., Freeman, K., Logan, A., & Frost, C. (2017). Floating Offshore: 55 Technology Innovations that will have greater impact on reducing the cost of electricity from European floating offshore wind farms. Retrieved from KiC InnoEnergy and BVG Associates website.

Lopez, A., Roberts, B., Heimiller, D., Blair, N., & Porro, G. (2012). U.S. Renewable Energy Technical Potentials: A GIS-Based Analysis (Technical Report No. NREL/TP-6A20-51946). https://doi.org/10.2172/1219777

Mines, G. (2013, April). Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model (GETEM). Presented at the Geothermal Technologies Office 2013 Peer Review, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2014/02/f7/mines_getem_peer2013.pdf

Moné, C., Smith, A., Maples, B., & Hand, M. (2015). 2013 Cost of Wind Energy Review (No. NREL/TP-5000-63267). https://doi.org/10.2172/1172936

Musial, Walt, Heimiller, D., Beiter, P., Scott, G., & Draxl, C. (2016). 2016 Offshore Wind Energy Resource Assessment for the United States (No. NREL/TP-5000-66599). https://doi.org/10.2172/1324533

Musial, Walter, Beiter, P., Spitsen, P., & Nunemaker, J. (2018). 2018 Offshore Wind Technologies Market Report. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/08/f65/2018%20Offshore%20Wind%20Market%20Report.pdf

Roberts, B. J. (2009). Geothermal Resource of the United States: Locations of Identified Hydrothermal Sites and Favorability of Deep Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS). Retrieved from https://www.nrel.gov/gis/images/geothermal_resource2009-final.jpg

Tester, J. W., & et al. (2006). The Future of Geothermal Energy: Impact of Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) on the United States in the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

USGS. (2008). Assessment of Moderate- and High-Temperature Geothermal Resources of the United States (No. Fact Sheet 2008-3082). Retrieved from U.S. Geological Survey website: https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3082/pdf/fs2008-3082.pdf

Valpy, B., Hundleby, G., Freeman, K., Roberts, A., & Logan, A. (2017). Future renewable energy costs: Offshore wind. Retrieved from KiC InnoEnergy and BVG Associates website: http://www.innoenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/InnoEnergy-Offshore-Wind-anticipated-innovations-impact-2017_A4.pdf