2019 ATB

For each electricity generation technology in the ATB, this website provides:

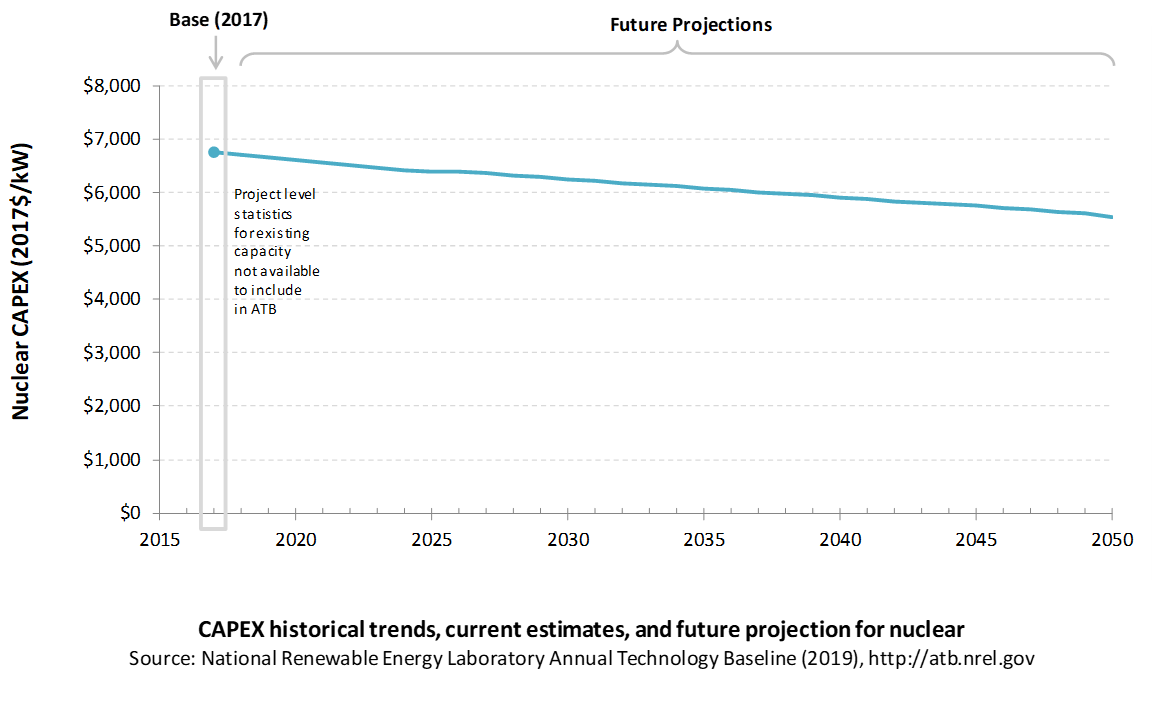

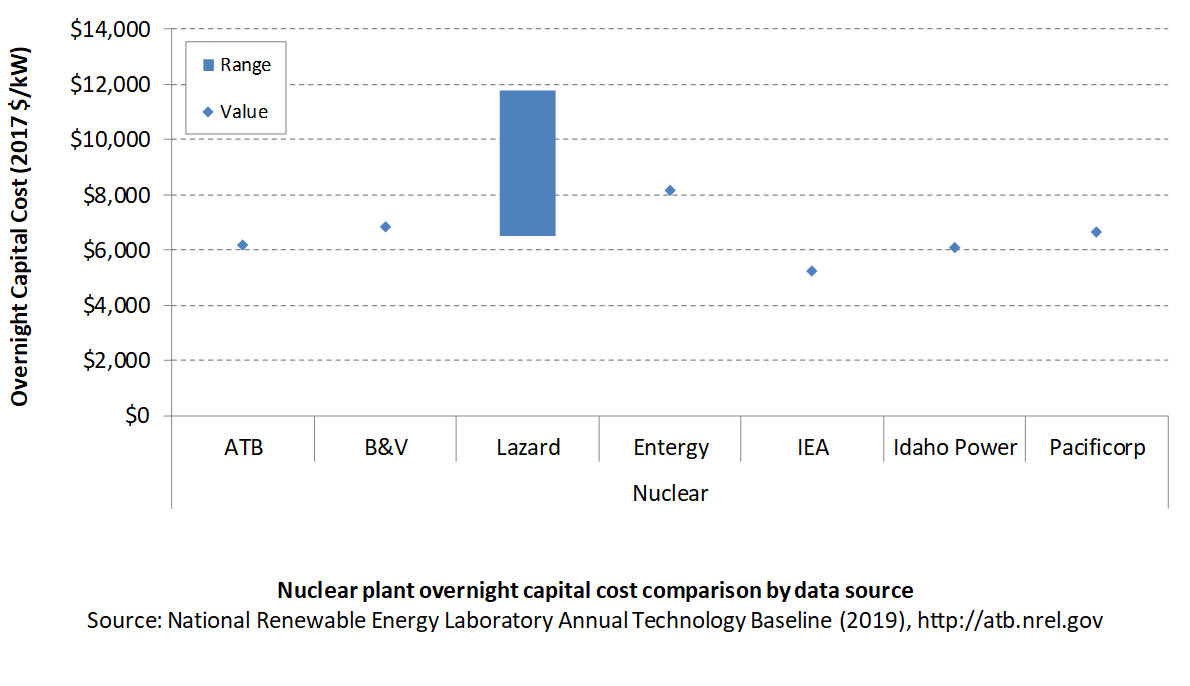

- Capital expenditures (CAPEX): the definition of CAPEX used in the ATB and the historical trends, current estimates, and future projections of CAPEX used in the ATB

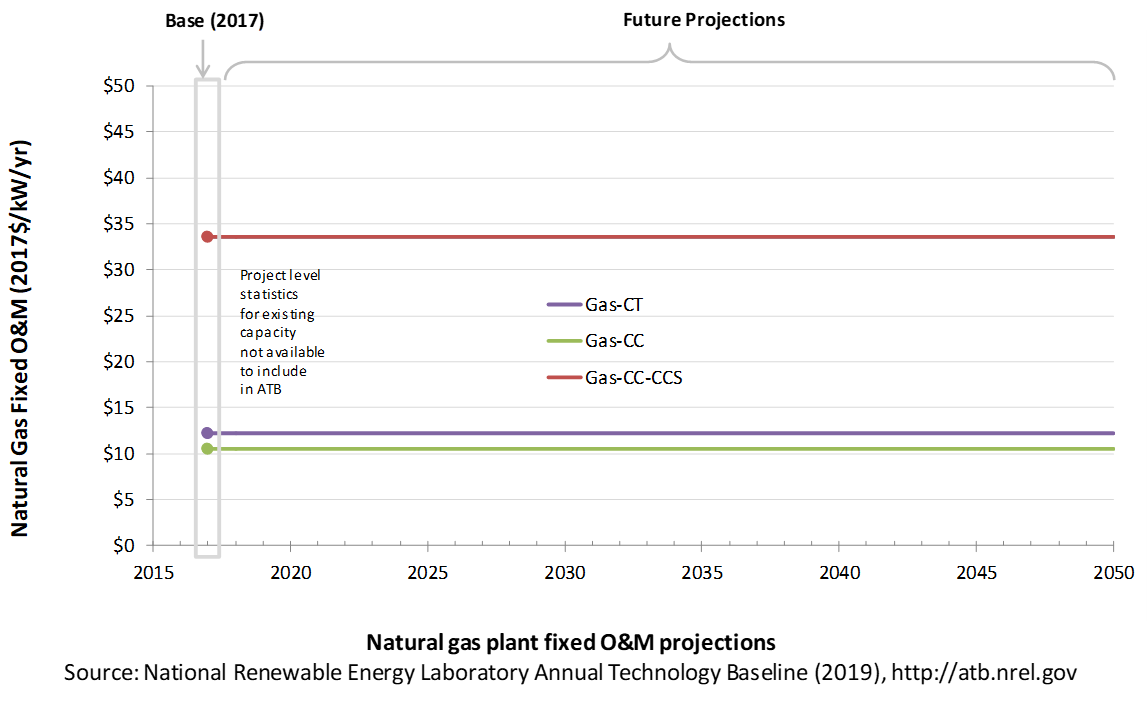

- Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs: the definition of O&M and the current estimates and future projections of O&M used in the ATB

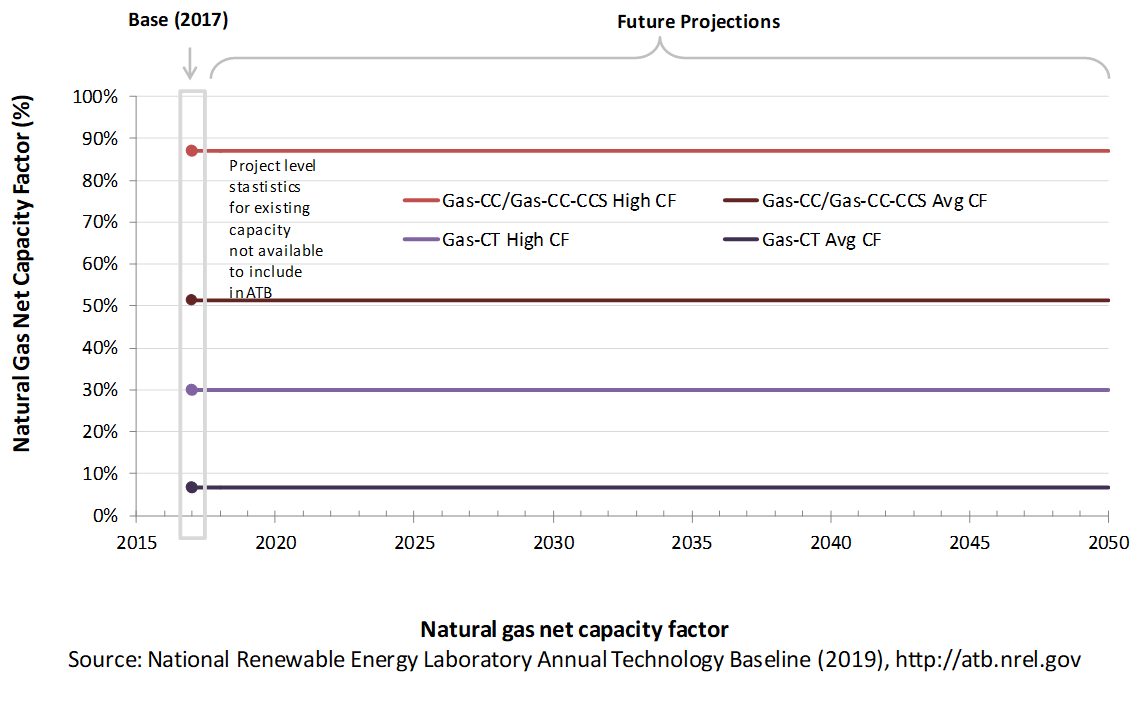

- Capacity factor (CF): the definition of CF and the historical trends, current estimates, and future projections of CF used in the ATB

- Future cost and performance methods: an outline of the methodology used to make the projections of future cost and performance in the ATB for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases

- Levelized cost of energy (LCOE): metric that combines CAPEX, O&M, CF, and projections for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases for illustration of the combined effect of the primary cost and performance components and discussion of technology advances that yield future projections

- Financing assumptions: development of technology-specific interest rate on debt, return on equity, and debt-to-equity ratios and their impact on LCOE are documented in each technology section, where applicable, and summarized here.

Electricity generation technologies are selected on the left side of the screen, and the topics highlighted above can be selected using the drop-down menu at the top right of the screen.

Guidelines for using and interpreting ATB content and comparisons to other literature are provided. LCOE accounts for many variables important to determining the competitiveness of building and operating a specific technology (e.g., upfront capital costs, capacity factor, and cost of financing); however, it does not necessarily demonstrate which technology in a given place and time would provide the lowest cost option for the electricity grid. Such analysis is performed using electric sector models such as the Regional Energy Deployment Systems (ReEDS) model and corresponding analysis results such as the NREL Standard Scenarios.

The NREL Standard Scenarios, a companion product to the ATB, provides a suite of electric sector scenarios and associated assumptions, including technology cost and performance assumptions from the ATB.

ATB data sources and references are also provided for each technology. All dollar values are presented in 2017 U.S. dollars, unless noted otherwise.

Additional information is available here: About the 2019 ATB.

Concentrating Solar Power

Representative Technology

Concentrating solar power (CSP) technology is currently assumed to be molten-salt power towers. Thermal energy storage (TES) is accomplished by storing hot molten salt in a two-tank system, which includes a hot-salt tank and a cold-salt tank. Stored hot salt can be dispatched to the power block as needed, regardless of solar conditions, to continue power generation and allow for electricity generation after sunlight hours. In the ATB, CSP plants with 10 hours of TES are illustrated. Ten hours is the amount of storage at the Crescent Dunes CSP plant in Nevada, which is representative of most new molten-salt power tower projects.

Molten-salt power towers (with 10 hours of storage) were selected as the representative technology over parabolic trough with synthetic oil-heat transfer fluid for two main reasons. First, most new global capacity of CSP plants in development or under construction are molten-salt power towers; in 2015, 3.7 GWe of molten-salt power towers were in development or under construction ((IRENA 2018), (SolarReserve n.d.)) – compared to 1.3 GWe of parabolic trough (IRENA 2018). Second, current indications are that molten-salt power towers have the greatest cost reduction potential, in terms of both CAPEX and LCOE ((IRENA 2016), (Mehos et al. 2017)). And they are part of the DOE Generation 3 (Gen3) road map for the next generation of commercial CSP plants (Mehos et al. 2017).

Crescent Dunes (110 MWe with 10 hours of storage) was the first large molten-salt power tower plant in the United States. It was commissioned in 2015 with a reported installed CAPEX of $8.96/WAC ((Danko 2015), (Taylor 2016)). No new molten salt storage CSP plants were commissioned in the United States in 2018 or 2019. Molten-salt power tower plants are being bid and built in Chile and Dubai (NREL and SolarPaces n.d.).

Resource Potential

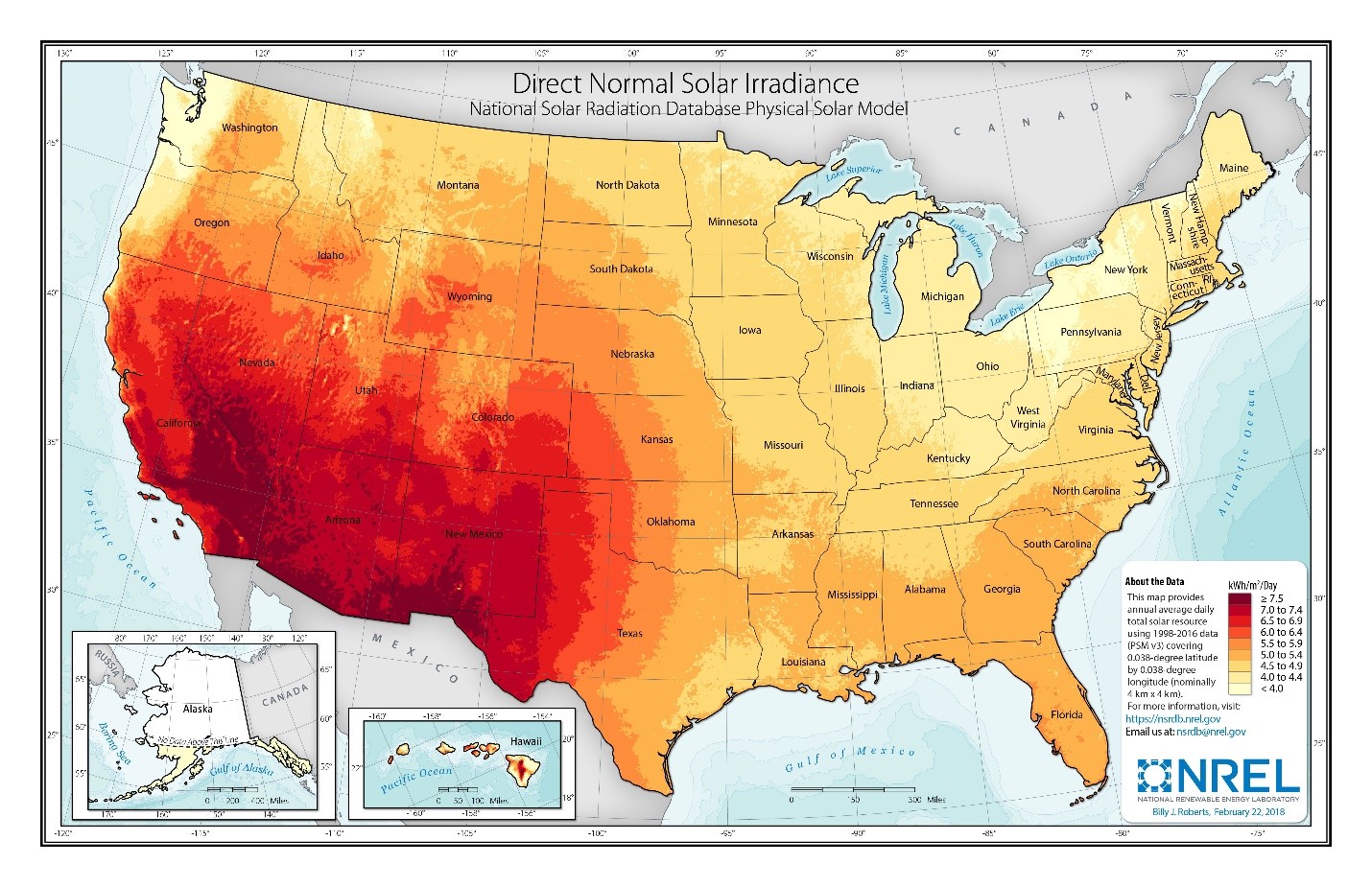

Solar resource is prevalent throughout the United States, but the Southwest is particularly suited to CSP plants. The direct normal irradiance (DNI) resource across the Southwest, which is some of the best in the world, ranges from 6.0 to more than 7.5 kWh/m2/day (Roberts 2018). The raw resource technical potential of seven western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Texas) exceeds 11,000 GWe, which is almost tenfold current total U.S. electricity generation capacity-considering regions in these states with an annual average resource > 6.0 kWh/m2/day. After accounting for exclusions such as land slope (> 1%), urban areas, water features, and parks, preserves, and wilderness areas (Mehos, Kabel, and Smithers 2009).

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012), represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential – resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

The Solar Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement identified 17 solar energy zones for priority development of utility-scale solar facilities in six western states. These zones total 285,000 acres and are estimated to accommodate up to 24 GWe of solar potential. The program also allows development, subject to a more rigorous review, on an additional 19 million acres of public land. Development is prohibited on approximately 79 million acres.

According to NREL's Concentrating Solar Power Projects website and the CSP Today Global Projects Tracker ("CSP Today Global Tracker" n.d.), 12 of the 14 currently operational CSP plants greater than 5 MWe in the United States use parabolic trough technology, and two are power tower facilities – Ivanpah (392 MWe, utilizing direct steam generation in the towers) and Crescent Dunes (110 MWe, as highlighted, utilizing molten-salt in the tower).

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

For the ATB, various factors are used to demonstrate the range of LCOE and performance across the United States. These include:

- CAPEX is determined using manufacturing cost models and is benchmarked with industry data. CSP performance and cost are based on the molten-salt power tower technology with dry-cooling to reduce water consumption.

- O&M cost is benchmarked against industry data.

- Capacity factor varies with inclusion of TES and solar irradiance. The listed resource classes assume power towers with 10 hours of TES at three types of locations:

- Fair resource (e.g., Abilene Regional Airport, Texas 6.16 kWh/m2/day based on the National Solar Radiation Database [NSRDB] site 2017 Physical Solar Model [PSM] TMY file)

- Good resource (e.g., Phoenix, Arizona 7.26 kWh/m2/day based on the site TMY3 file)

- Excellent resource (e.g., Daggett, California 7.65 kWh/m2/day based on the site TMY3 file)

- Representative CSP plant size is net 100 MWe.

The CSP costs originated from: (1) a NREL survey leading to updated cost estimates in the System Advisor Model (SAM) 2017.09.05; and (2) further cost estimates for CSP components which are now present in SAM 2018.11.11 (Craig Turchi et al. 2019). These SAM 2018 CSP costs were deflated to the ATB Base Year of 2017 via the consumer price index. The SAM 2018 costs translate to ATB costs in 2021 due to the three-year construction period. (SAM costs are based on the project announcement year, while the ATB is based on the plant commissioning year).

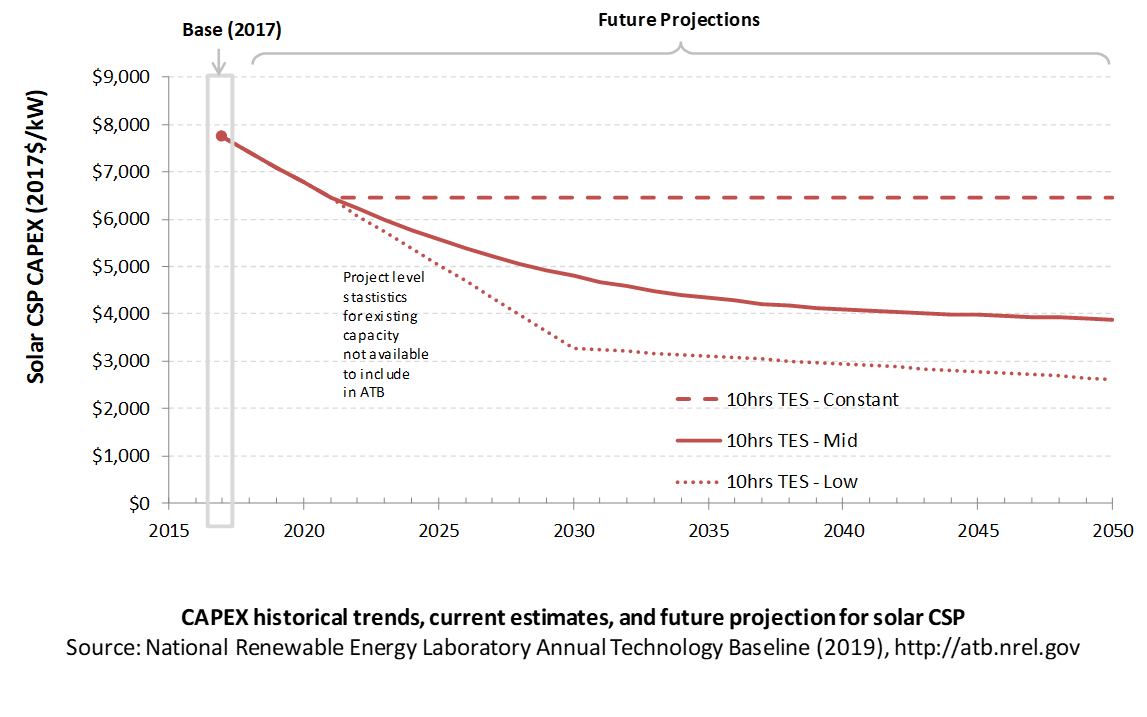

Future year projections are informed by a variety of published literature, NREL expertise and technology pathway assessments for CAPEX and O&M cost reductions. Three different projections were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from current estimates (2021 for CSP) to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- The Mid Technology Cost Scenario is based on recently published literature projections and NREL judgment of U.S. costs for future CAPEX at 2025, 2030, 2040 and 2050 ((IRENA 2016), (Breyer et al. 2017), (Feldman et al. 2016), and (World Bank 2014)). It is anticipated that CSP costs could fall by approximately 25% from the ATB CSP 2021 costs of $6,450/kWe to approximately $4,800/kWe by 2030. From 2030 to 2050, CSP CAPEX is projected to fall to approximately $3,380/kWe.

- The Low Technology Cost Scenario is based on the lower bound of the literature sample, and on the Power to Change report (IRENA 2016).

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the generation plant, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with resource in the contiguous United States.

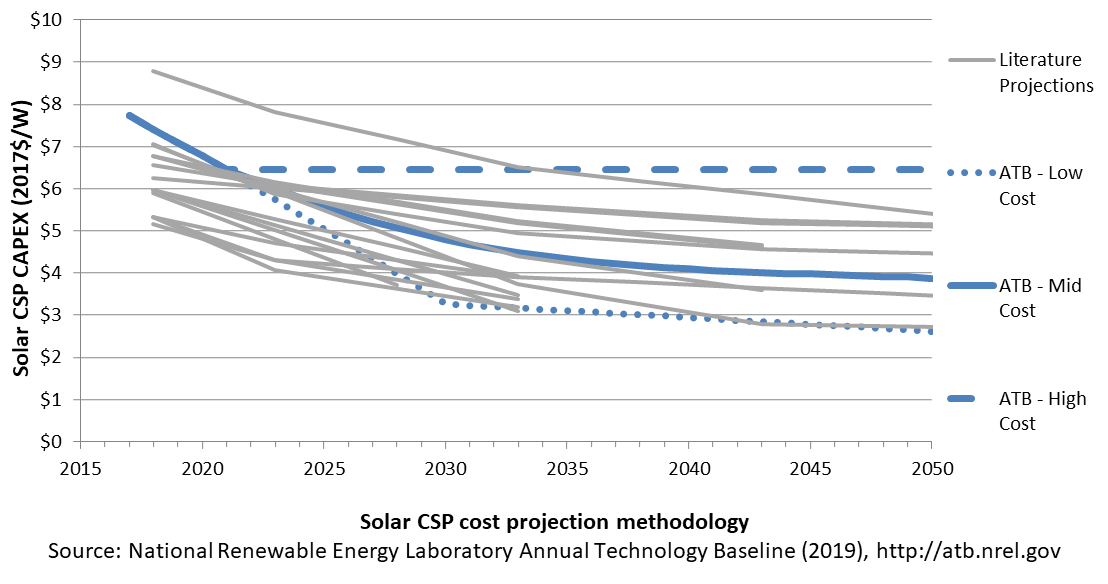

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs. Three cost scenarios are represented: Constant, Mid, and Low. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year (i.e., SAM 2018 CSP costs are reflected in the ATB in 2021).

Base Year Estimates

CAPEX is unchanged for resource class because the same plant is assumed to be built in each location. The capacity factor will change with resource.

TES increases plant CAPEX but also increases capacity factor and annual efficiency. TES generally lowers LCOE for power towers.

The CAPEX estimate (with a base year of 2017) is approximately $7,730/kWe in 2017$. It is for a representative power tower with 10 hours of storage and a solar multiple of 2.4. Based on recent assessment of the industry in 2017 and updated CSP systems costs reflected in SAM 2018.11.11 (Craig Turchi et al. 2019), the CAPEX estimate for 2021 is $6,450/kWe in 2017$.

Future Year Projections

Three cost projections are developed for CSP technologies:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from current estimates (2021 for CSP) to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- The Mid Technology Cost Scenario is based on recently published literature projections and NREL judgment of U.S. costs for future CAPEX at 2025, 2030, 2040 and 2050 ((IRENA 2016), (Breyer et al. 2017), (Murphy et al. 2019), (Feldman et al. 2016), and (World Bank 2014)). It is anticipated that CSP costs could fall by approximately 25% from the ATB CSP 2021 costs of $6,450/kWe to approximately $4,800/kWe by 2030. From 2030 to 2050, CSP CAPEX is projected to fall to approximately $3,380/kWe.

- The Low Technology Cost Scenariois based on the lower bound of the literature sample, and on the Power to Change report (IRENA 2016).

Relative to today's reported CAPEX for plants either announced or in construction, $6,450/kWe in the ATB in 2021 and $4,800/kWe in 2030 is possible. For example, Noor III (150 MWe molten salt power tower with 7.5 hours of storage and operational in 2018), had an estimated CAPEX of $6,500/kWe in 2017$ (Kistner 2016). The Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) 700-MWe CSP portion (600-MWe parabolic trough and 100-MWe molten salt tower, each with 12-15 hours of storage), which is in construction had an estimated bundled CAPEX of $5,500/kWe ( (Shemer 2018), (Craig Turchi et al. 2019)).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

The ATB represents the year in which a plant starts commercial operation. Accordingly, for plants whose construction duration exceeds one year, CAPEX costs will represent technology costs that are lagging current-year estimates by at least one year. For CSP plants, the construction period is typically three years.

For the ATB – and based on key sources ((EIA 2016), (C. Turchi 2010), and (Craig Turchi and Heath 2013)) – the CSP generation plant envelope is defined to include:

- CSP generation plant

- Solar collectors

- Solar receiver

- Piping and heat-transfer fluid system

- Power block (heat exchangers, power turbine, generator, and cooling system)

- Thermal energy storage system

- Installation

- Balance of system, including installation, land acquisition, electrical infrastructure, and project indirect costs

- Land acquisition, site preparation, and installation of underground utilities, access roads, fencing, and buildings for operations and maintenance

- Electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting modules to each other and to control the center; the generator voltage is 13.8 kV, the step-up transformer is 13.8/230kV, and the transmission tie line is 230 kV

- Project indirect costs, including costs related to engineering, distributable labor and materials, construction management start up and commissioning, and contractor overhead costs, fees, and profit

- Financial costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Onsite electrical equipment (e.g., switchyard), a nominal-distance spur line (< 1 mile), and necessary upgrades at a transmission substation; distance-based spur line cost (GCC) not included in the ATB

- Interest during construction estimated based on three-year duration accumulated 80%/10%/10% at half-year intervals and a nominal interest rate (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

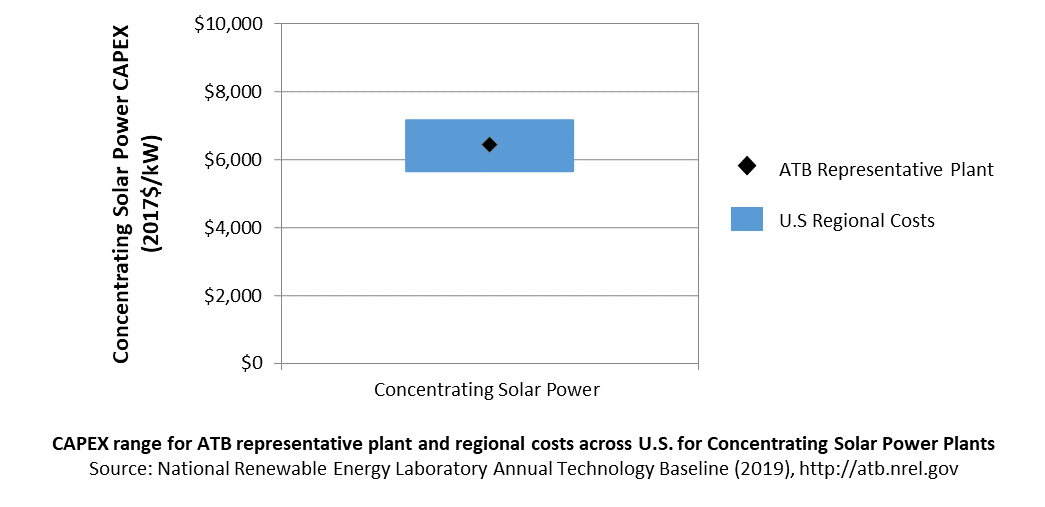

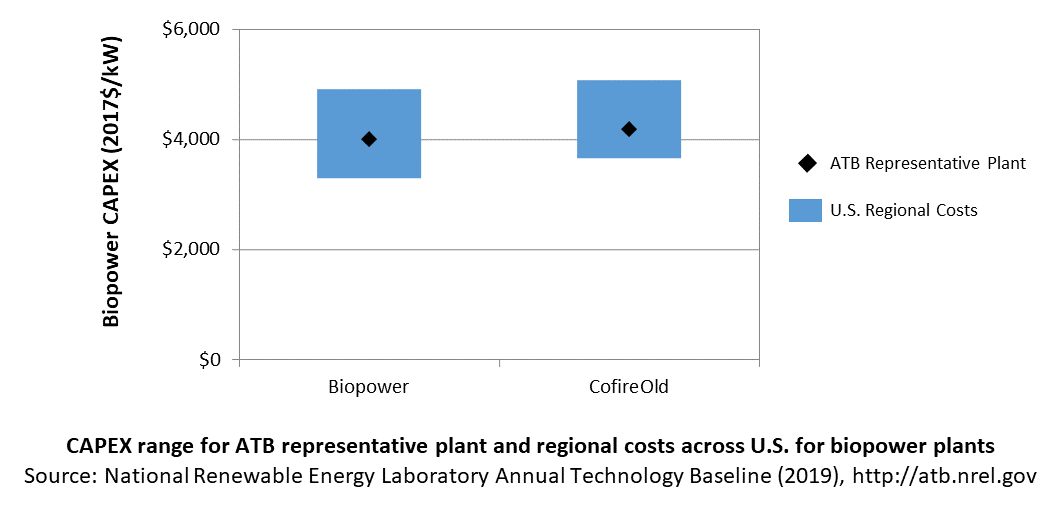

In the ATB, CAPEX represents a typical solar-CSP plant with 10 hours of thermal storage and does not vary with resource. Regional cost effects associated with labor rates, material costs, and other regional effects as defined by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA 2016) expand the range of CAPEX. Unique land-based spur line costs based on distance and transmission line costs expand the range of CAPEX even further. The following figure illustrates the ATB representative plant relative to the range of CAPEX including regional costs across the contiguous United States. The ATB representative plants are associated with a regional multiplier of 1.0.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., but the ReEDS model does include 134 regional multipliers (EIA 2016).

The ReEDS model determines the land-based spur line (GCC) uniquely for each potential CSP plant based on distance and transmission line cost.

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent the annual expenditures required to operate and maintain a solar CSP plant over its lifetime, including:

- Operating and administrative labor, insurance, legal and administrative fees, and other fixed costs

- Utilities (water, power, and natural gas if any) and mirror washing

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance, including replacement parts for solar field and power block components over the technical lifetime of the plant.

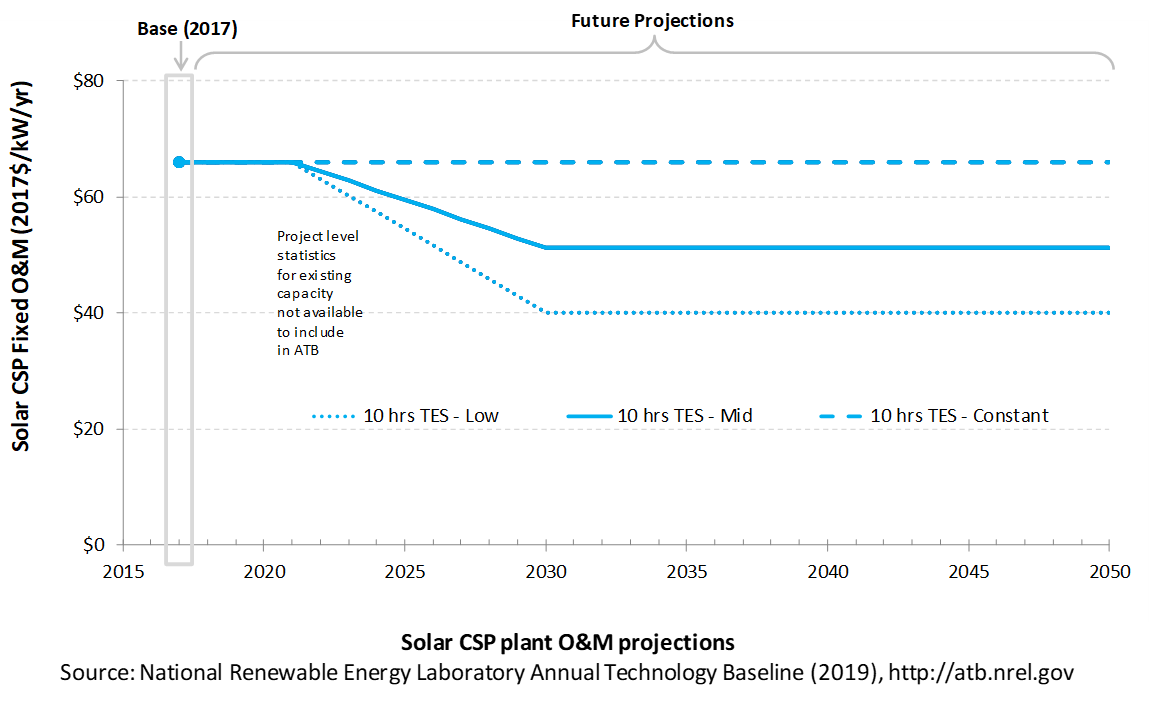

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed O&M (FOM) costs. Three cost scenarios are represented. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

FOM is assumed to be $66/kW-yr until 2021. Variable O&M is approximately $4.1/MWh until 2021 and $3.50/MWh after that (Kurup and Turchi 2015).

Future Year Projections

Future FOM is assumed to decline to $51/kW-yr by 2030 in the Mid cost case (i.e., approximately a 25% drop) and approximately $40/kW-yr by 2030 in the Low cost case based on DOE investments likely to help to lower costs (DOE 2012).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

Capacity factors are influenced by power block technology, storage technology and capacity, the solar resource, expected downtime, and energy losses. The solar multiple is a design choice that influences the capacity factor.

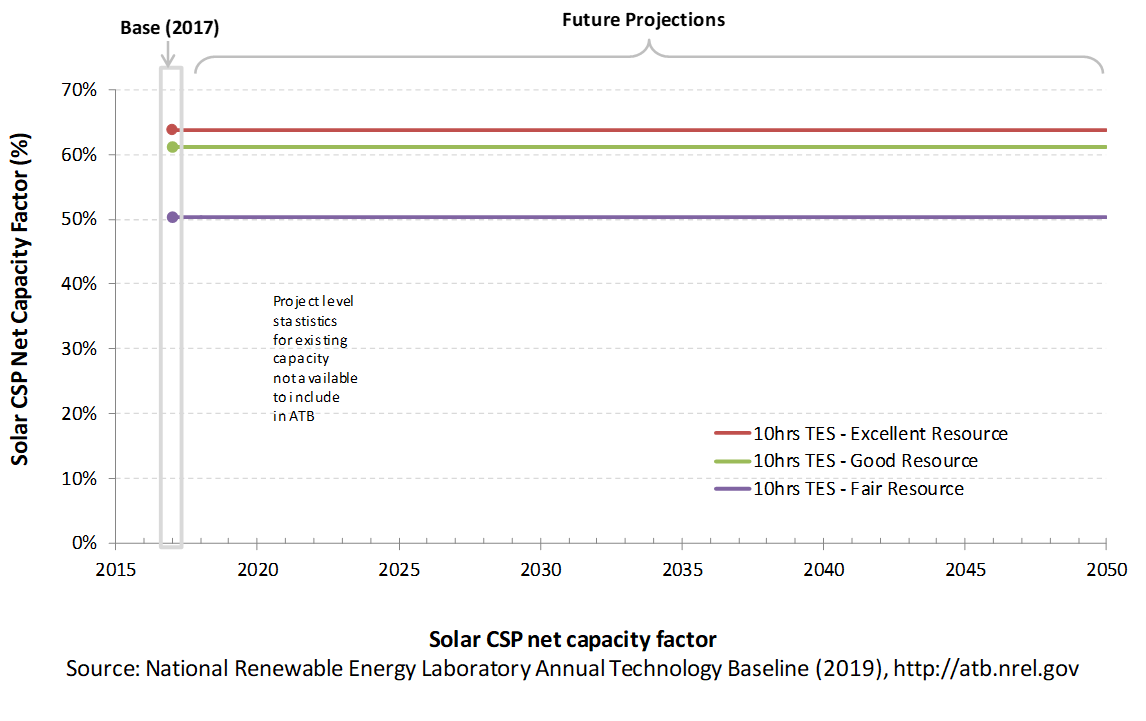

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in the resource, for locations where currently CSP plants could be built in the contiguous United States. The range of the Base Year estimates illustrates the effect of locating a CSP plant at a site with Fair, Good, or Excellent solar resource. The future projections for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are unchanged from the Base Year. Technology improvements are focused on CAPEX and O&M cost elements.

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, a range of capacity factors calculated in SAM 2018.11.11 (NREL n.d.) is associated with three resource locations in the contiguous United States, as represented in the ReEDS model for three classes of insolation:

- Fair resource: Abilene, Texas: 6.16 kWh/m2/day based on the site TMY3 file, leads to a 50% capacity factor; the 2017 PSM TMY file for a site adjacent to the airport is used, and it was downloaded from the NSRDB (NREL n.d.).

- Good resource: Phoenix, Arizona: 7.26 kWh/m2/day based on the site TMY3 leads to a 61% capacity factor; the TMY file used is available in SAM 2018.11.11(NREL n.d.), titled "phoenix_az_33.450495_-111.983688_psmv3_60_tmy"..

- Excellent resource: Daggett, California: 7.65 kWh/m2/day based on the site TMY3 file, leads to a 64% capacity factor; the TMY file used is available in SAM 2018.11.11 (NREL n.d.), titled "daggett_ca_34.865371_-116.783023_psmv3_60_tmy".

A key finding from a recent report is that if future costs of CSP decrease sufficiently, it could be deployed across a greater range of the United States and DNI resources. For example, with aggressive cost decreases and due to the regional market constraints, southeastern states with lower DNI resources (e.g., Florida and South Carolina) could see increased CSP capacity deployments of up to 5 GWe (Murphy et al. 2019).

Future Year Projections

The CSP technologies highlighted in the ATB are assumed to be power towers but with different power cycles and operating conditions as time passes:

- 2017: a molten-salt (sodium nitrate/potassium nitrate; aka, solar salt) power tower with direct two-tank TES combined with a steam-Rankine power cycle running at 574° C and 41.2% gross efficiency

- 2021: a similar design to that of 2017 with identified near-term reductions in heliostat and power system costs

- 2030 Mid Technology Cost Scenario: longer-term cost reductions (e.g., in the heliostats and power system)

- 2030 Low Technology Cost Scenario: In the ATB, the Low projection is based on molten-salt power tower with direct two-tank TES combined with a power cycle running at 700° C and 55% gross efficiency.

While an advanced molten salt projection is used for the ATB Low Cost scenario, lower costs for baseload CSP are being investigated via different technology options (i.e. Solid Particle and Gas phase towers) and as defined by the CSP Gen3 program ((EERE n.d.), (Mehos et al. 2017)).

Over time, CSP plant output may decline. Capacity factor degradation due to mirror and other component degradation is not accounted for in ATB estimates of capacity factor or LCOE.

The ATB capacity factors are generated from Constant, Mid and Low technology cost plant simulations in SAM 2018.11.11 (NREL n.d.).

Estimates of capacity factors for CSP in the ATB represent typical operation. The dispatch characteristics of these systems are valuable to the electric system to manage changes in net electricity demand. Actual capacity factors will be influenced by the degree to which system operators call on CSP plants to manage grid services.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CSP plants with TES can be dispatched by grid operators to accommodate diurnal and seasonal load variations and output from variable generation sources (wind and solar PV). Because of this, their annual energy production and the value of that generation are determined by the electric system needs and capacity and ancillary services markets.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

A range of literature projections is shown to illustrate the comparison with the ATB. When comparing the ATB projections with other projections, note that there are major differences in technology assumptions, radiation conditions, field sizes, storage configurations, and other factors. As shown in the chart, the ATB 2019 CSP Mid projection is in line with other recently analyzed projections from other organizations. The Low cost ATB projection is based on the lower bound of the literature sample, and on the Power to Change report (IRENA 2016).

Projections of future utility-scale CSP plant CAPEX and O&M are based on three different technology cost scenarios that were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario

- Modeled as molten-salt (sodium nitrate/potassium nitrate, aka, solar salt) power tower with direct two-tank TES combined with a steam-Rankine power cycle running at 574°C and 41.2% gross efficiency in 2017

- Costs stay the same from the 2021 estimate through 2050, consistent with ATB renewable energy technologies

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario:

- Based on recently published literature projections and NREL judgment of U.S. costs for future CAPEX in 2025, 2030, 2040 and 2050 ((IRENA 2016), (Breyer et al. 2017), (Murphy et al. 2019), (Feldman et al. 2016), and (World Bank 2014)).

- It is anticipated that CSP costs could fall by approximately 25% from the ATB CSP 2021 costs of $6,450/kWe to approximately $4,800/kWe by 2030.

- CSP CAPEX is projected to fall from 2030 to 2050 to approximately $3,380/kWe.

- The cost reductions are anticipated due to gradual reductions in heliostat and power system cost due to greater deployment volume and learning assumed for 2021 and onwards based on current state of industry ((IRENA 2016), (Lilliestam et al. 2017)).

- CAPEX and O&M both drop by approximately 25% by 2030, relative to 2021 costs

- A further 30% overall CAPEX decrease is estimated from 2030 to 2050. All three components of the CSP CAPEX (the turbine, storage, and the solar field), decrease proportionately by approximately 30% from 2030 to 2050.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario:

- Significant reductions in heliostat and power system cost due to greater deployment volume and R&D are used for 2021 onwards; the plant was modeled as an advanced molten-salt power tower with direct two-tank TES combined with a power cycle running at 700°C and 55% gross efficiency in 2030 (Mehos et al. 2017).

- CAPEX and O&M decrease from likely cost reductions including new high-efficiency power cycles and low-cost heliostats.

- A further 20% overall CAPEX decrease is assumed from 2030 to 2050 based on potential deployment in the United States. The 20% decrease in overall CSP CAPEX is split over the three components: the turbine, storage, and the solar field. It can be expected that greater cost reductions could be achieved for the power block/turbine and the solar field than for the storage.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a summary metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies such as CSP can provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

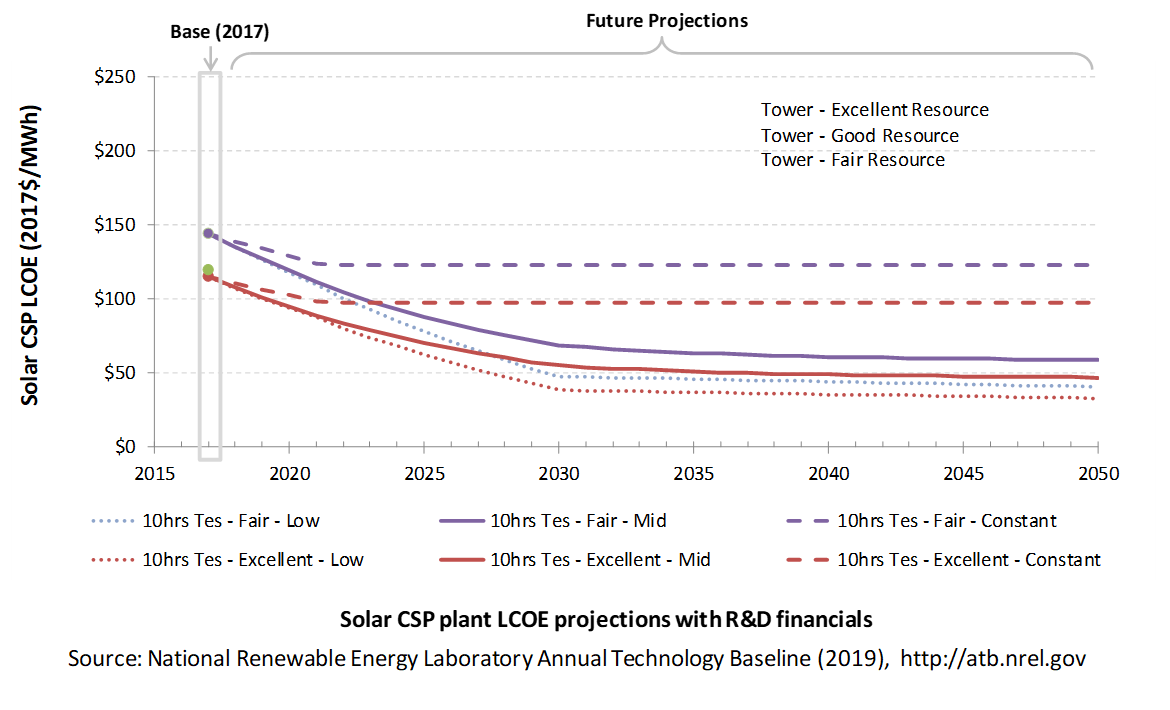

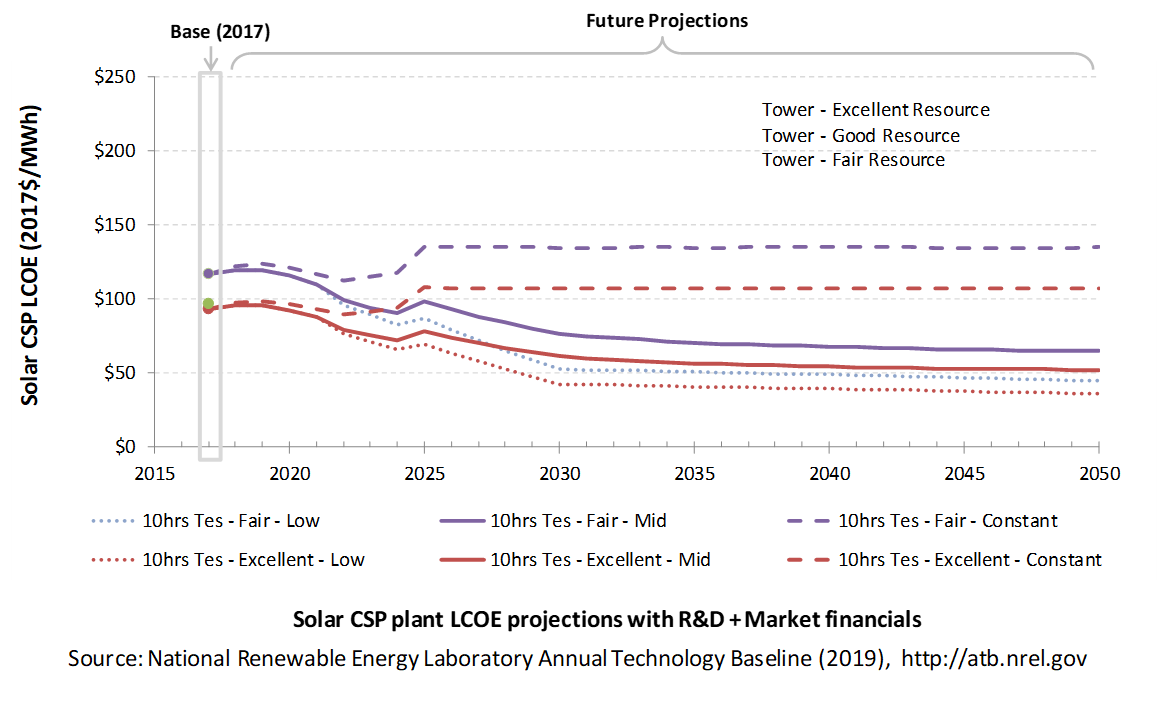

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for power-tower CSP across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs but not in the upfront capital costs (e.g., developer fees and contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside the United States, due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g., offshore wind in Europe) or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform and tax credits. For example, the projected LCOE for most utility scale renewable energy generation technologies could potentially increase from the end of 2020 due to the decreasing levels of the ITC. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term CSP plants are associated with Tower-Excellent Resource. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures.

Note: the future projection of the "Good resource" (i.e., for a CSP plant built in Phoenix, Arizona) is not shown in the figures to simplify the figures and because the projection lies between the Excellent and the Fair Resource projections.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA 2019) and excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2019 (EIA 2019) as well as effects of tax reform and tax credits. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE.

A constant cost recovery period – over which the initial capital investment is recovered – of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below.

- Power tower improvements

- Better and longer-lasting selective surface coatings improve receiver efficiency and reduce O&M costs.

- New salts allow for higher operating temperatures and lower-cost TES.

- Development of the power cycle running at approximately 700°C and 55% gross efficiency improves cycle efficiency, reduces powerblock cost, and reduces O&M costs.

- Lower-cost heliostats developed due to design changes and automated and high-volume manufacturing.

- General and "soft" costs improvements

- Expansion of world market leads to greater and more efficient supply chains, and reduction of supply chain margins (e.g., profit and overhead charged by suppliers, manufacturer, distributors, and retailers).

- Expansion of access to a range of innovative financing approaches and business models

- The LCOE range shown is based on locations with Fair (Abilene, Texas), Good (Phoenix, Arizona), and Excellent (Daggett, California) resources. The CAPEX is the same for each resource as the same plant is used. Future-year LCOE projections for the Good case are not shown to simplify the figure. Using the R&D Only scenario and financials, and with the capacity factor of 64% for Daggett, California (NREL n.d.), in the Mid case by 2030, the LCOE could reach approximately 55$/MWh, and it could potentially reach $47/MWh by 2050.

Geothermal

Geothermal technology cost and performance projections have been updated with analysis and results from the GeoVision: Harnessing the Heat Beneath our Feet report (DOE, 2019). The GeoVision report is a collaborative multiyear effort with contributors from industry, academia, national laboratories, and federal agencies. The analysis in the report updates resource potential estimates as well as current and projected capital and O&M costs based on rigorous, bottom-up modeling.

Representative Technology

Hydrothermal geothermal technologies encompass technologies for exploring for the resource, drilling to access the resource, and building power plants to convert geothermal energy to electricity. Technology costs depend heavily on the hydrothermal resource temperature and well productivity and depth, so much so that project costs are site-specific and applying a "typical" cost to any given site would be inaccurate. The 2019 ATB uses scenarios developed by the DOE Geothermal Technology Office (Mines, 2013) for representative binary and flash hydrothermal power plant technologies. The first scenario assumes a 175°C resource at a depth of 1.5 km with wells producing an average of 110 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 30-MWe binary (organic Rankine cycle) power plant. The second scenario assumes a 225°C resource at a depth of 2.5 km with wells producing 80 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 40-MWe dual-flash plant. These are mid-grade or "typical" temperatures and depths for binary and flash hydrothermal projects. The ReEDS model uses the full hydrothermal supply curve. The 2019 ATB representative technologies fall in the middle or near the end of the hydrothermal resources typically deployed in ReEDS model runs.

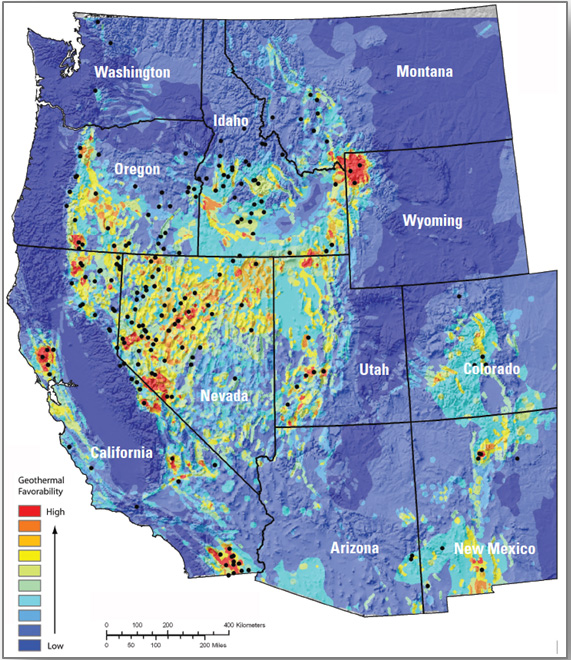

Resource Potential

The hydrothermal geothermal resource is concentrated in the western United States. The total mean potential is 39,090 MW: 9,057 MW identified and 30,033 MW undiscovered (USGS, 2008). The resource potential identified by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, 2008) at each site is based on available reservoir thermal energy information from studies conducted at the site. The undiscovered hydrothermal technical potential estimate is based on a series of GIS statistical models for the spatial correlation of geological factors that facilitate the formation of geothermal systems.

The U.S. Geological Survey resource potential estimates for hydrothermal were used with the following modifications:

- Installed capacity of about 3 GW in 2016 is excluded from the resource potential.

- Resources on federally protected and U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) lands, where development is highly restricted are excluded from the resource potential, as are resources on lands where significant barriers that prevent or inhibit development of geothermal projects were identified by Augustine, Ho, and Blair (2019).

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012), represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential-resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

The Base Year cost and performance estimates are calculated using Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model (GETEM), a bottom-up cost analysis tool that accounts for each phase of development of a geothermal plant (DOE "Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model").

- Cost and performance data for hydrothermal generation plants are estimated for each potential site using GETEM. Model results are based on resource attributes (e.g., estimated reservoir temperature, depth, and potential) of each site. GETEM inputs are derived from the Business-as-Usual (BAU) scenario from GeoVision ( (DOE, 2019), (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)).

- Site attribute values are from (USGS, 2008) for identified resource potential and from capacity-weighted averages of site attribute values of nearby identified resources for undiscovered resource potential.

- GETEM is used to estimate CAPEX, O&M, and parasitic plant losses that affect net energy production.

Capacity factor and O&M costs for plants installed in future years are unchanged from the Base Year. Projections for hydrothermal and EGS technologies are equivalent.

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX cost reduction based on assumed minimum learning as implemented in AEO (EIA, 2015): 10% by 2035; this corresponds to a 0.5% annual improvement in CAPEX, which is assumed to continue on through 2050

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX based on the Technology Improvement scenario from GeoVision Study ( (DOE, 2019); (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)); cost and technology improvements change linearly from present values and are fully achieved by 2030.

Representative Technology

As with cost for projects that use hydrothermal resources, EGS resource project costs depend so heavily on the hydrothermal resource temperature and well productivity and depth that project costs are site-specific. The 2019 ATB uses scenarios developed by the DOE Geothermal Technology Office (Mines, 2013) for representative binary and flash EGS power plants assuming current (immature) EGS technology performance metrics. The first scenario assumes a 175°C resource at a depth of 3 km with wells producing an average of 40 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 25-MWe binary (organic Rankine cycle) power plant. The second scenario assumes a 250°C resource at a depth of 3.5 km with wells producing 40 kg/s of geothermal brine supplied to a 30-MWe dual-flash plant. These temperatures and depths are at the low-cost end of the EGS supply curve and would be some of the first developed. The ReEDS model uses the full EGS supply curve. Neither of these technologies is typically used.

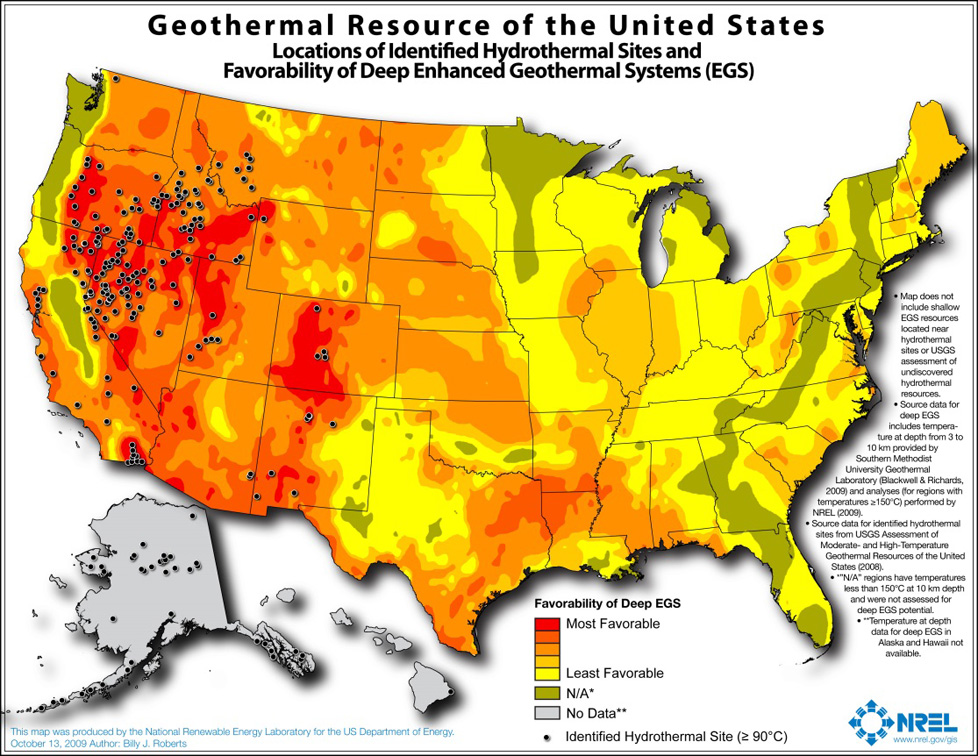

Resource Potential

The enhanced geothermal system (EGS) resource is concentrated in the western United States. The total potential is greater than 100,000 MW: 1,493 MW of near-hydrothermal field EGS (NF-EGS) and the remaining potential comes from deep EGS.

Renewable energy technical potential as defined by Lopez et al. (2012) represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, environmental, and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand there are multiple types of potential-resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

The Base Year cost and performance estimates are calculated using the Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model (GETEM), a bottom-up cost analysis tool that accounts for each phase of development of a geothermal plant (DOE "Geothermal Electricity Technology Evaluation Model").

- Cost and performance data for EGS generation plants are estimated for each potential site using GETEM. Model results based on resource attributes (e.g., estimated reservoir temperature, depth, and potential) of each site. GETEM inputs are derived from the GeoVision BAU scenario ( (DOE, 2019), (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)).

- Approaches to restrict resource potential to about 500 GW based on USGS analysis may be implemented in the future.

- GETEM is used to estimate CAPEX and O&M and parasitic plant losses that affect net energy production.

Capacity factor and O&M costs for plants installed in future years are unchanged from the Base Year. Projections for hydrothermal and enhanced geothermal system technologies are equivalent.

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050, consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX cost reduction based on assumed minimum learning as implemented in AEO (EIA, 2015): 10% by 2035; this corresponds to a 0.5% annual improvement in CAPEX, which is assumed to continue on through 2050.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX based on the GeoVision Technology Improvement scenario ( (DOE, 2019), (Augustine, Ho, & Blair, 2019)). Cost and technology improvements decrease linearly from present values and are fully achieved by 2030.

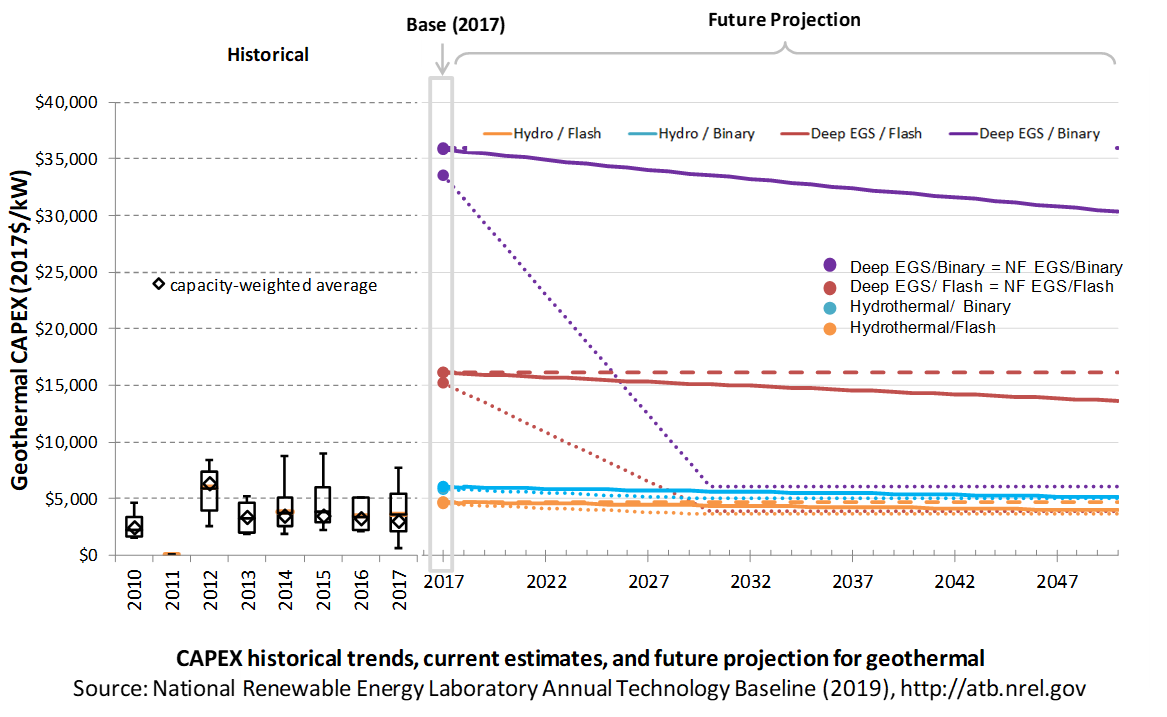

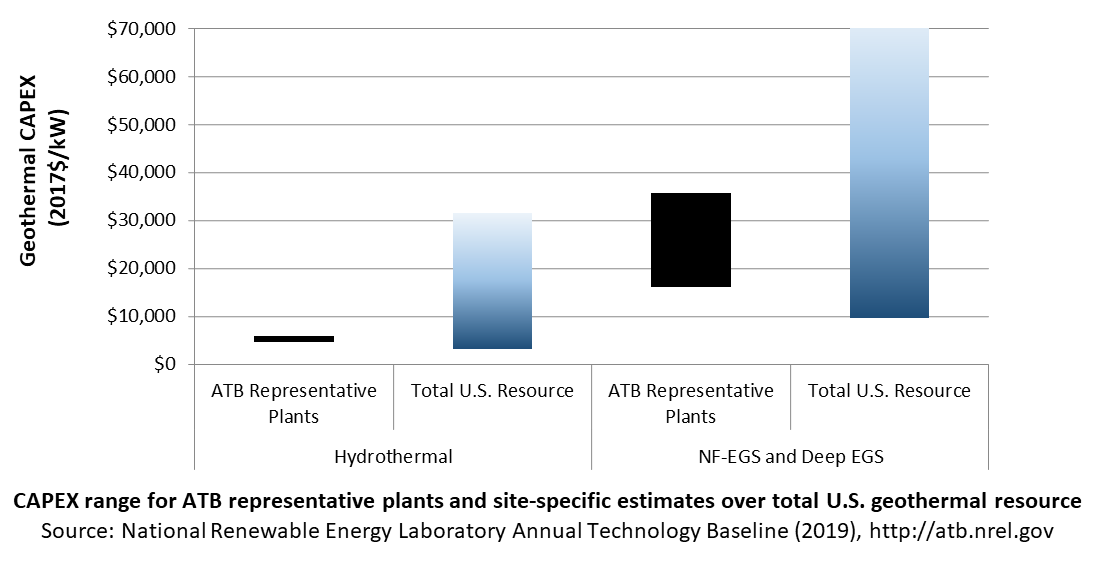

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the geothermal generation plant, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with resource in the contiguous United States.

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs. Three cost scenarios are represented: Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, six representative geothermal plants are shown. Two energy conversion processes are common: binary organic Rankine cycle and flash.

- Binary plants use a heat exchanger to transfer geothermal energy to an organic Rankine cycle. This technology generally applies to lower-temperature systems. These systems have higher CAPEX than flash systems because of the increased number of components, their lower-temperature operation, and a general requirement that a number of wells be drilled for a given power output.

- Flash plants create steam directly from the thermal fluid through a pressure change. This technology generally applies to higher-temperature systems. Due to the reduced number of components and higher-temperature operation, these systems generally produce more power per well, thus reducing drilling costs. These systems generally have lower CAPEX than binary systems.

Examples using each of these plant types in each of the three resource types (hydrothermal, NF-EGS, and deep EGS) are shown in the ATB.

Costs are for new or greenfield hydrothermal projects, not for re-drilling or additional development/capacity additions at an existing site.

Characteristics for the six examples of plants representing current technology were developed based on discussion with industry stakeholders. The CAPEX estimates were generated using GETEM. CAPEX for NF-EGS and EGS are equivalent.

The following table shows the range of OCC associated with the resource characteristics for potential sites throughout the United States.

| Temp (°C) | >=200C | 150-200 | 135-150 | <135 | |

| Hydrothermal | Number of identified sites | 21 | 23 | 17 | 59 |

| Total capacity (MW) | 15,338 | 2,991 | 820 | 4,632 | |

| Average OCC ($/kW) | 3,906 | 7,720 | 8,794 | 16,248 | |

| Min OCC ($/kW) | 3,000 | 4,140 | 7,004 | 10,950 | |

| Max OCC ($/kW) | 5,491 | 29,135 | 11,027 | 21,349 | |

| Example of plant OCC ($/kW) | 4,229 | 5,455 | |||

| NF-EGS | Number of sites | 12 | 20 | ||

| Total capacity (MW) | 787 | 596 | |||

| Average OCC ($/kW) | 11,041 | 26,077 | |||

| Min OCC ($/kW) | 8,778 | 18,172 | |||

| Max OCC ($/kW) | 18,009 | 39,987 | |||

| Example of plant OCC ($/kW) | 14,512 | 32,268 | |||

| Deep EGS (3-6 km) | Number of sites | n/a | n/a | ||

| Total capacity (MW) | 100,000+ | ||||

| Average OCC ($/kW) | 28,418 | 60,170 | |||

| Min OCC ($/kW) | 18,320 | 39,329 | |||

| Max OCC ($/kW) | 54,047 | 77,983 | |||

| Example of plant OCC ($/kW) | 14,512 | 32,268 | |||

Future Year Projections

Projection of future geothermal plant CAPEX for the Low case is based on the GeoVision Technology Improvement scenario (DOE, 2019).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

For the ATB – and based on (EIA, 2016) and GETEM component cost calculations – the geothermal plant envelope is defined to include:

- Geothermal generation plant

- Exploration, confirmation drilling, well field development, reservoir stimulation (EGS), plant equipment, and plant construction

- Power plant equipment, well-field equipment, and components for wells (including dry/non-commercial wells)

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Installation and electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting turbines to each other and to the control center

- Project indirect costs, including costs related to engineering, distributable labor and materials, construction management start up and commissioning, and contractor overhead costs, fees, and profit

- Financial costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Electrical interconnection and onsite electrical equipment (e.g., switchyard), a nominal-distance spur line (<1 mile), and necessary upgrades at a transmission substation; distance-based spur line cost (GCC) not included in the ATB

- Interest during construction estimated based on four-year and five-year duration for hydrothermal and EGS respectively (for the low scenario) and an eight-year duration and ten-year duration for hydrothermal and EGS respectively (for the mid- and constant-scenario) accumulated at different intervals for hydro and EGS based on scheduled at outlined by the GeoVision Study (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

In the ATB, CAPEX is shown for six representative plants. Examples of CAPEX for binary organic Rankine cycle and flash energy conversion processes in each of three geothermal resource types are presented. CAPEX estimates for all hydrothermal NF-EGS potential results in a CAPEX range that is much broader than that shown in the ATB. It is unlikely that all the resource potential will be developed due to the high costs for some sites. Regional cost effects and distance-based spur line costs are not estimated.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model represents cost and performance for hydrothermal, NF-EGS, and EGS potential in 5 bins for each of 134 geographic regions, resulting in a greater CAPEX range in the reference supply curve than what is shown in examples in the ATB.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., and neither does the ReEDS model.

CAPEX in the ATB does not include geographically determined spur line (GCC) from plant to transmission grid, and neither does the ReEDS model.

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent average annual fixed expenditures (and depend on rated capacity) required to operate and maintain a hydrothermal plant over its lifetime of 30 years (plant and reservoir), including:

- Insurance, taxes, land lease payments, and other fixed costs

- Present value and annualized large component overhaul or replacement costs over technical life (e.g., downhole pumps)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of geothermal plant components and well field components over the technical lifetime of the plant and reservoir.

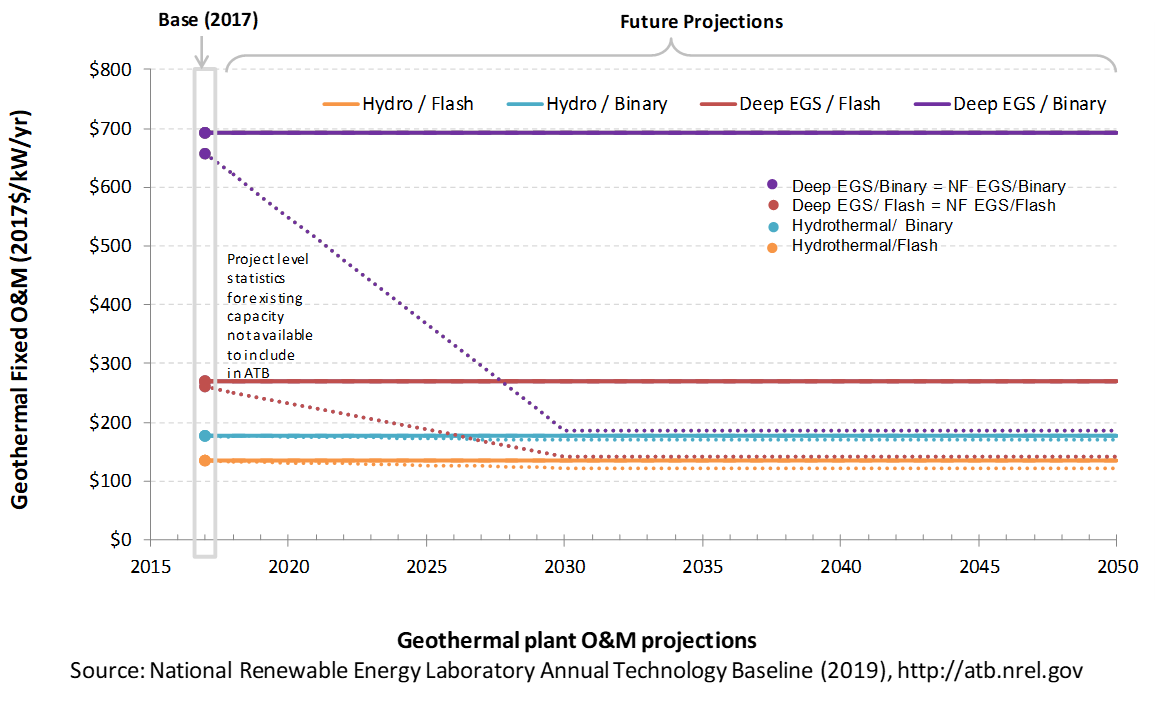

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed O&M (FOM) costs. Three cost scenarios are represented. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

FOM is estimated for each example of a plant based on technical characteristics.

GETEM is used to estimate FOM for each of the six representative plants. FOM for NF-EGS and EGS are equivalent.

Future Year Projections

Future FOM cost reductions are based on results from the GeoVision scenario (DOE, 2019) and are described in detail in Augustine, Ho, and Blair (2019).

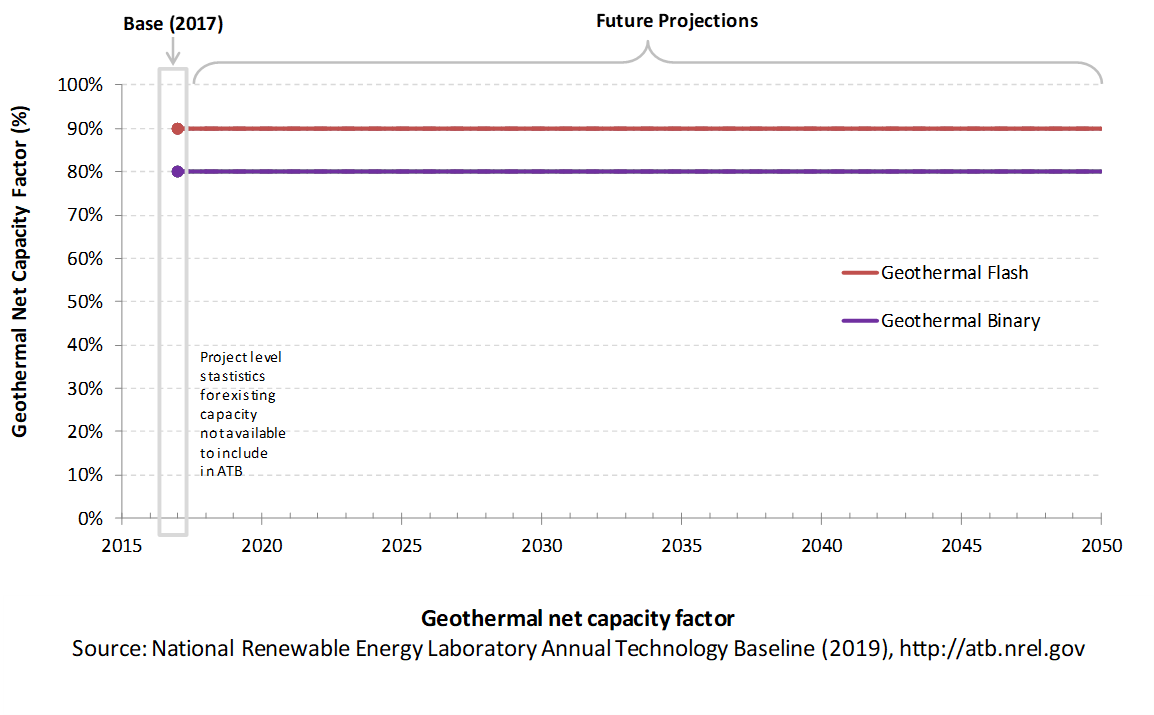

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the technical lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

Geothermal plant capacity factor is influenced by diurnal and seasonal air temperature variation (for air-cooled plants), technology (e.g., binary or flash), downtime, and internal plant energy losses.

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in the resource for plants in the contiguous United States. The range of the Base Year estimates illustrates Binary or Flash geothermal plants. Future year projections for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are unchanged from the Base Year. Technology improvements are focused on CAPEX cost elements.

Base Year Estimate

The capacity factor estimates are developed using GETEM at typical design air temperature and based on design plant capacity net losses. An additional reduction is applied to approximate potential variability due to seasonal temperature effects.

Some geothermal plants have experienced year-on-year reductions in energy production, but this is not consistent across all plants. No approximation of long-term degradation of energy output is assumed.

Ongoing work at NREL and the Idaho National Laboratory is helping improve capacity factor estimates for geothermal plants. As this work progresses, it will be incorporated into future versions of the ATB.

Future Year Projections

Capacity factors remain unchanged from the Base Year through 2050. Technology improvements are focused on CAPEX costs. Estimates of capacity factor for geothermal plants in the ATB represent typical operation. The dispatch characteristics of these systems are valuable to the electric system to manage changes in net electricity demand. Actual capacity factors will be influenced by the degree to which system operators call on geothermal plants to manage grid services.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

The site-specific nature of geothermal plant cost, the relative maturity of hydrothermal plant technology, and the very early stage development of EGS technologies make cost projections difficult. No thorough literature reviews have been conducted for cost reduction of hydrothermal geothermal technologies or EGS technologies. However, the GeoVision BAU scenario is based on a bottom-up analysis of costs and performance improvements. The inputs for the BAU scenario were developed by the national laboratories as part of the GeoVision effort, and it was reviewed by industry experts.

Projection of future geothermal plant CAPEX for the Low cost case is based on the GeoVision Technology Improvement scenario. It assumes that cost and technology improvements are achieved by 2030 and that costs decrease linearly from present values to the 2030 projected values. The Mid cost case is based on minimum learning rates as implemented in AEO (EIA, 2015): 10% by 2035. This corresponds to a 0.5% annual improvement in CAPEX, which is assumed to continue on through 2050. The Constant technology cost scenario retains all cost and performance assumptions equivalent to the Base Year through 2050.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a simple metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies such as geothermal, can provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

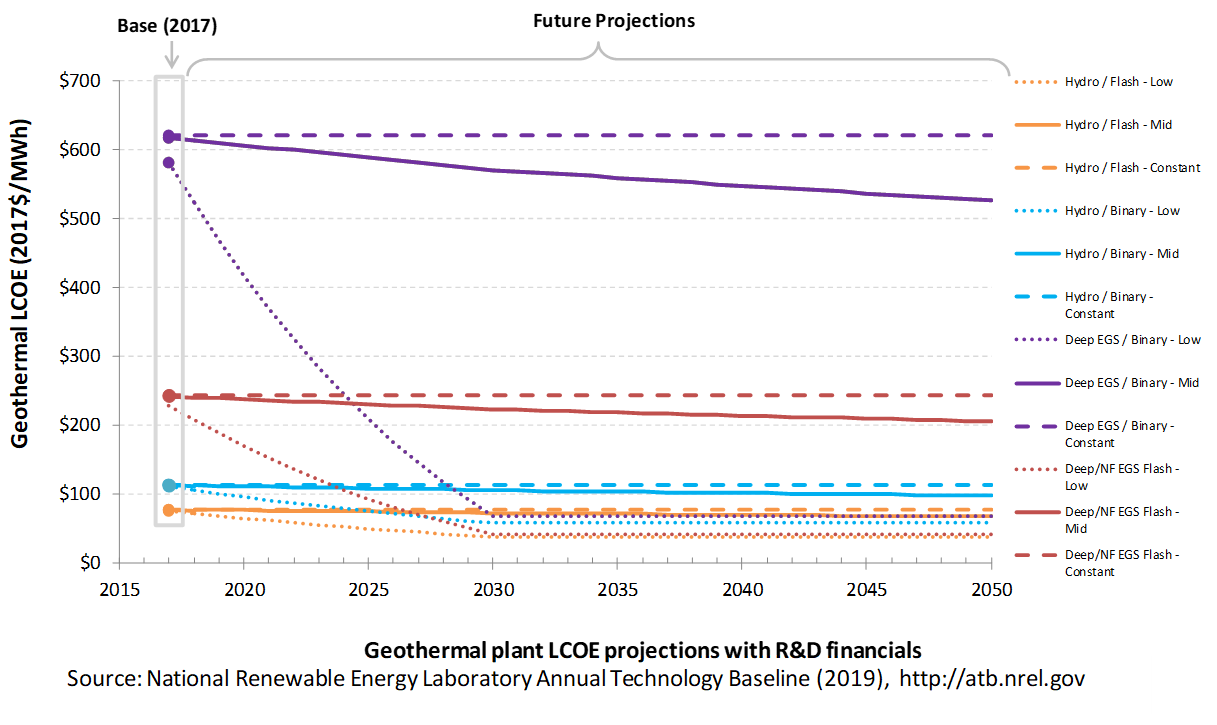

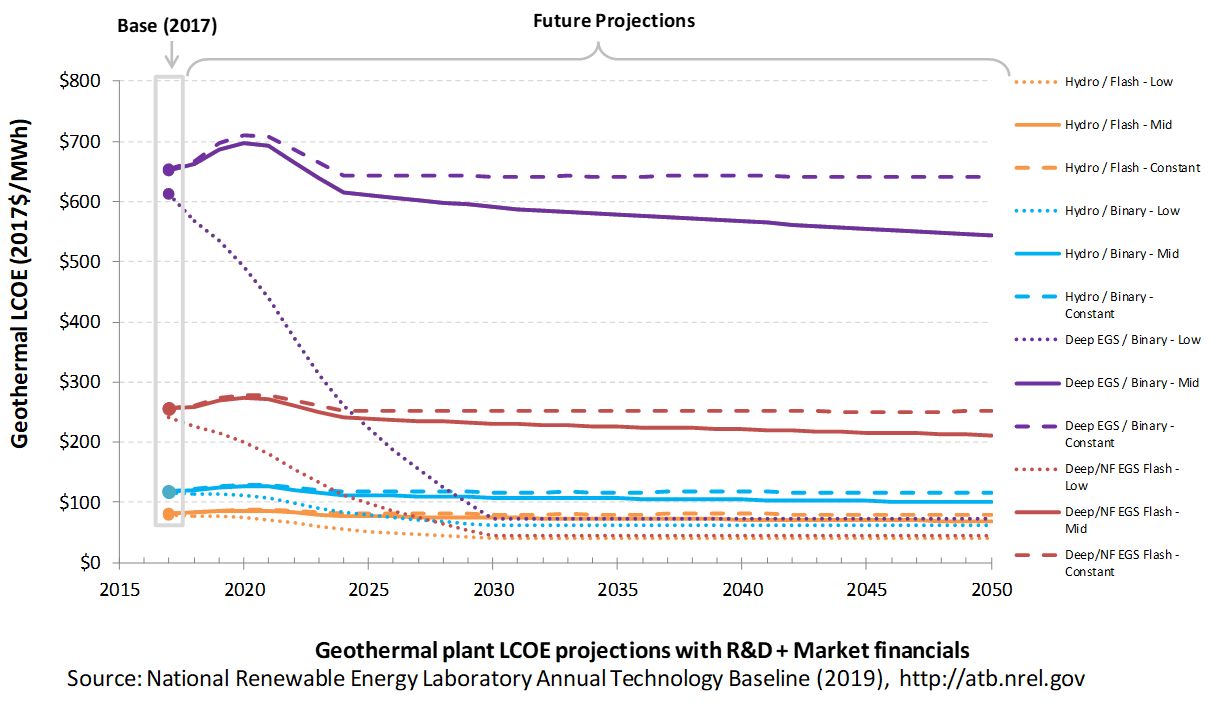

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for geothermal across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs but not in the upfront capital costs (e.g., developer fees and contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside the United States, due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g., offshore wind in Europe) or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, technology-specific tariffs, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term geothermal plants are associated with Hydrothermal/Flash. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA, 2019) and excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2018, as well as effects of tax reform, tax credits, and technology-specific tariffs. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Changes from 2018 ATB to 2019 ATB.

A constant cost recovery period – over which the initial capital investment is recovered – of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below.

- Development of exploration and reservoir characterization tools that reduce well-field costs through risk reduction by locating and characterizing low- and moderate-temperature hydrothermal systems prior to drilling

- High-temperature tools and electronics for geothermal subsurface operations

- Development of reservoir engineering techniques and technologies that enable EGS

- More efficient drilling practices and advanced drilling systems such as using flames or lasers to drill through rock; drilling steering technology; and other technologies to reduce drilling costs.

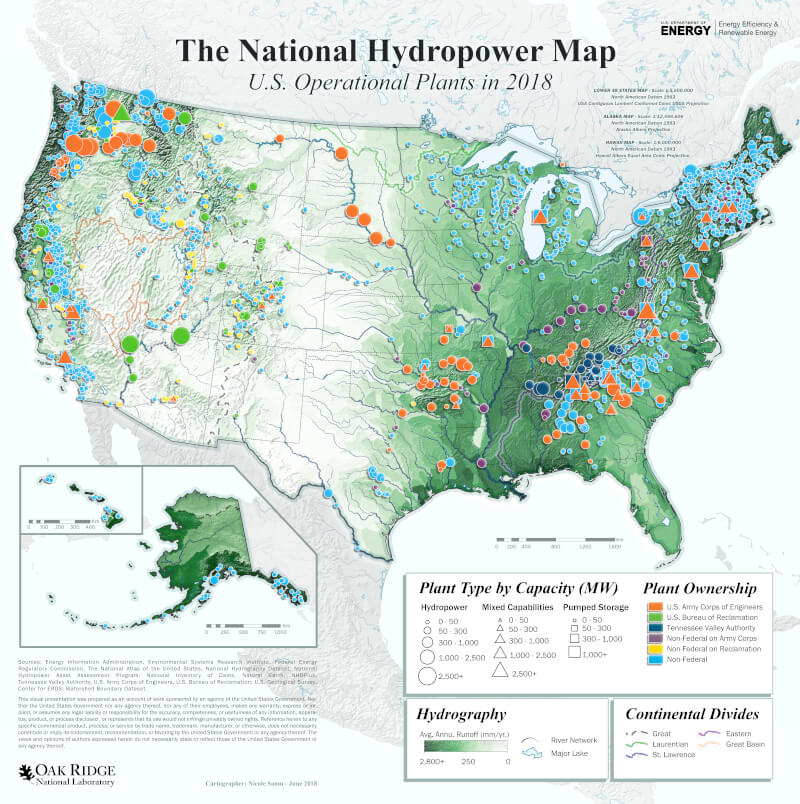

Hydropower

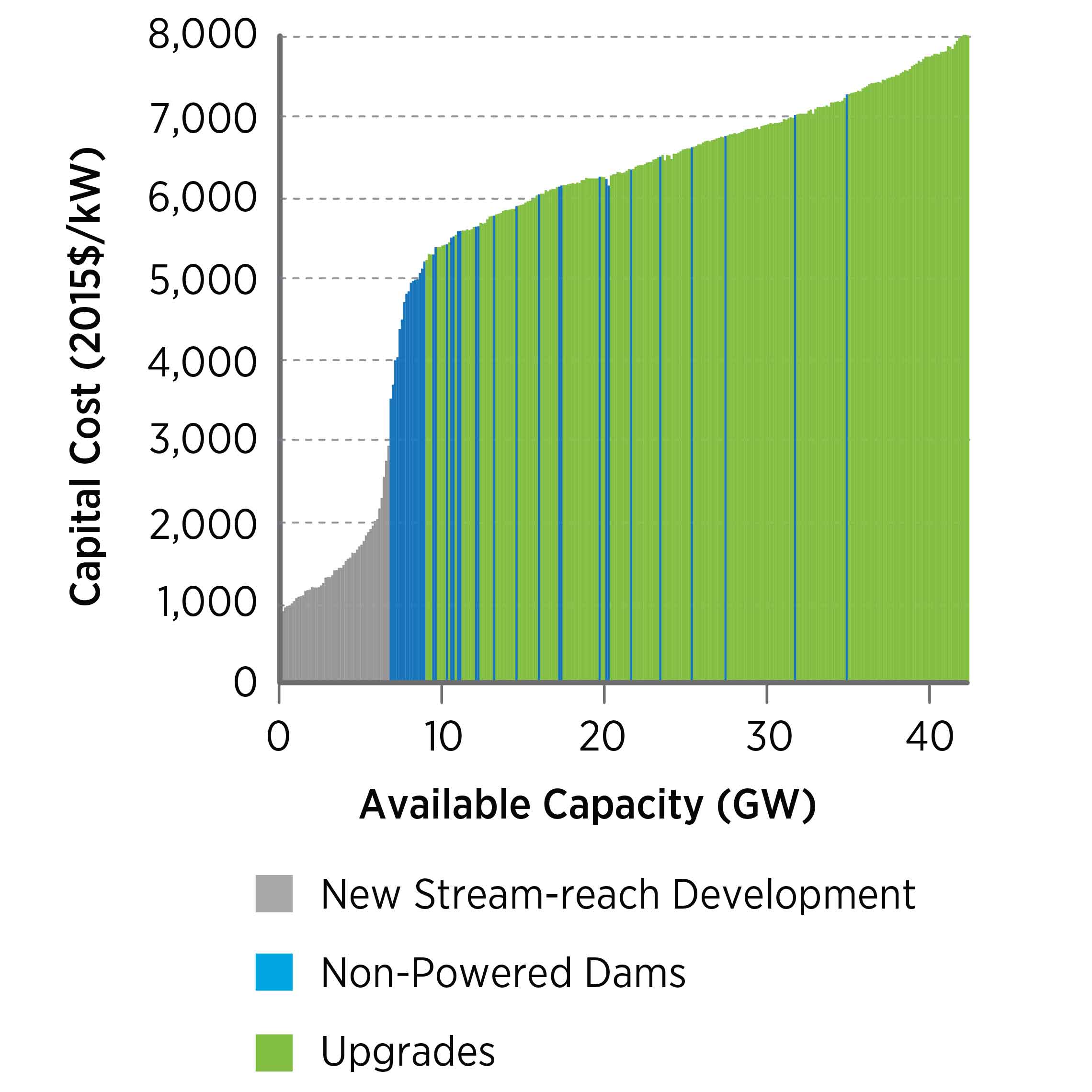

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012) , represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential-resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Note: Pumped-storage hydropower is considered a storage technology in the ATB and will be addressed in future years. It and other storage technologies are represented in Standard Scenarios Model Results from the ReEDS model, and battery storage technologies are shown in the associated portion of the ATB.

Representative Technology

Hydropower technologies have produced electricity in the United States for over a century. Many of these infrastructure investments have potential to continue providing electricity in the future through upgrades of existing facilities (DOE, 2016) . At individual facilities, investments can be made to improve the efficiency of existing generating units through overhauls, generator rewinds, or turbine replacements. Such investments are known collectively as "upgrades," and they are reflected as increases to plant capacity. As plants reach a license renewal period, upgrades to existing facilities to increase capacity or energy output are typically considered. While the smallest projects in the United States can be as small as 10-100 kW, the bulk of upgrade potential is from large, multi-megawatt facilities.

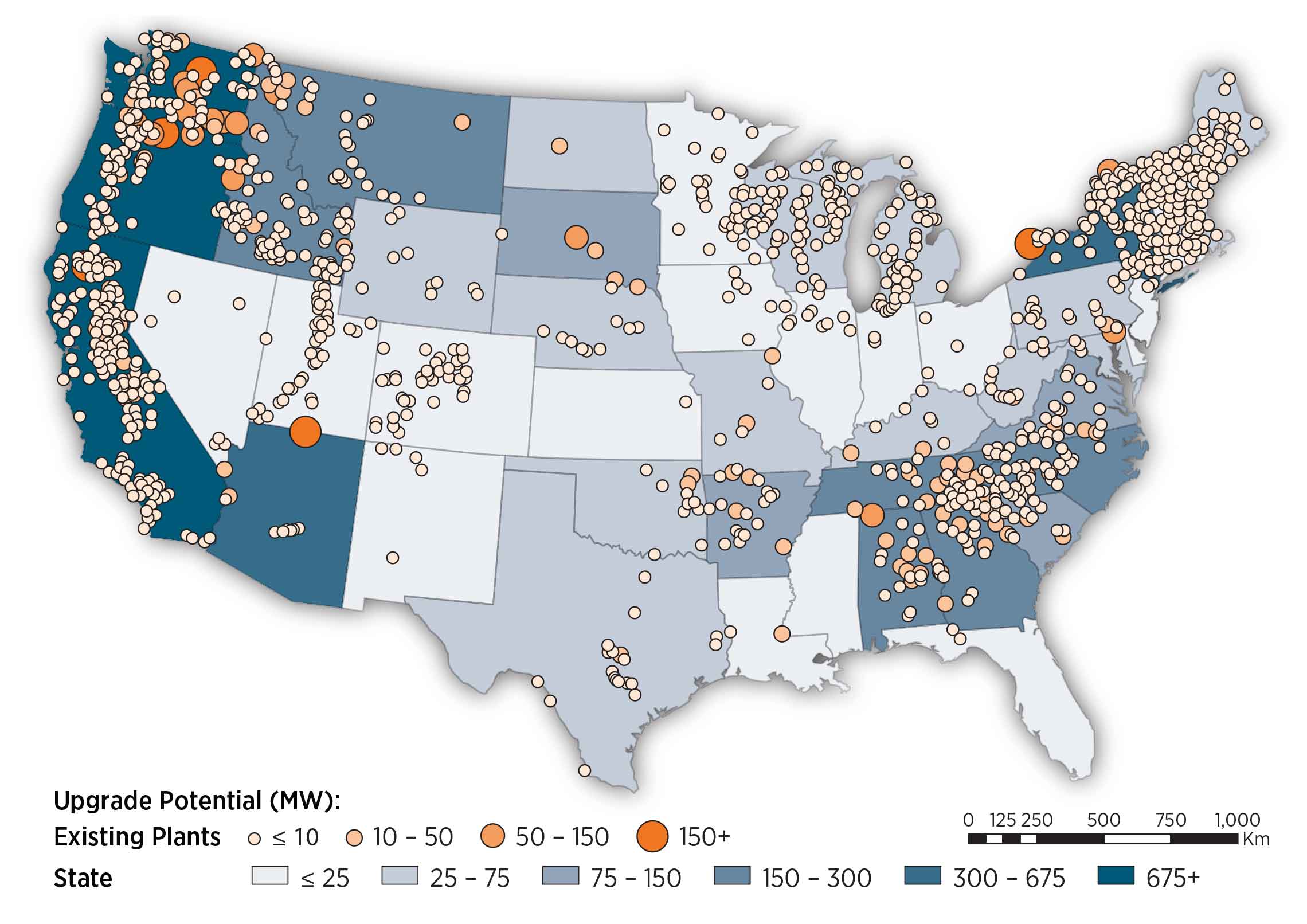

Resource Potential

The estimated total upgrade potential of 6.9 GW/24 terawattt-hours (TWh) (at about 1,800 facilities) is based on generalizable information drawn from a series of case studies or owner-specific assessments (DOE, 2016) . Information available to inform the representation of improvements to the existing fleet includes:

- A systematic, full-fleet assessment of expansion potential at Reclamation projects performed under the Reclamation Hydropower Modernization Initiative (see U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, "Hydropower Resource Assessment at Existing Reclamation Facilities")

- Case study reports from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) performed under its Hydropower Modernization Initiative (MWH, Watson, & Harza, 2009)

- Case study reports combining assessments of upgrade and unit and plant optimization potential from the U.S. Department of Energy/Oak Ridge National Laboratory Hydropower Advancement Project.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

Upgrades are often among the lowest-cost new capacity resource, with the modeled costs for individual projects ranging from $800/kW to nearly $20,000/kW. This differential results from significant economies of scale from project size, wherein larger capacity plants are less expensive to upgrade on a dollar-per-kilowatt basis than smaller projects are. The average cost of the upgrade resource is approximately $1,500/kW.

CAPEX for each existing facility is based on direct estimates

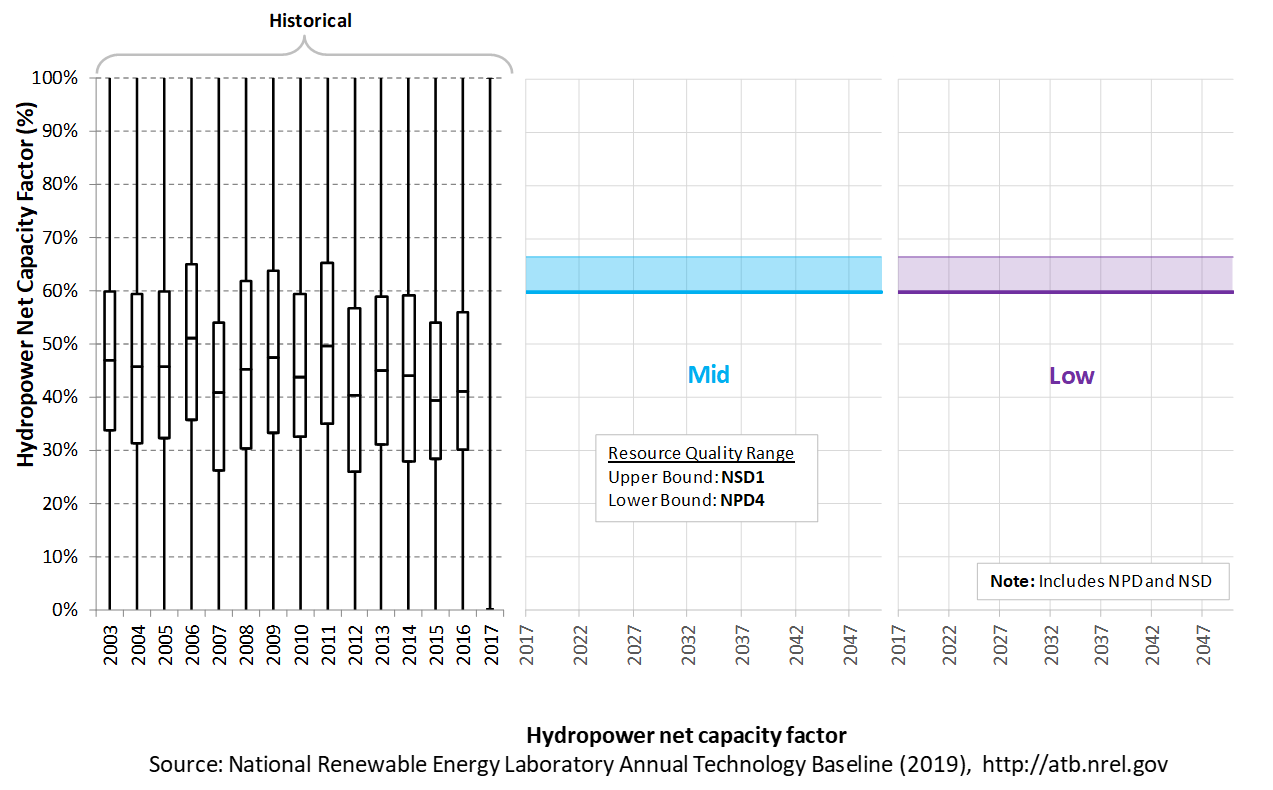

The capacity factor is based on actual 10-year average energy production reported in EIA 923 forms. Some hydropower facilities lack flexibility and only produce electricity when river flows are adequate. Others with storage capabilities are operated to meet a balance between electric system, reservoir management, and environmental needs using their dispatch capability.

No future cost and performance projections for hydropower upgrades are assumed.

Upgrade cost and performance are not illustrated in this documentation of the ATB for the sake of simplicity.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

Upgrade potential becomes available in the ReEDS model at the relicensing date, end of plant life (50 years), or both.

Representative Technology

Non-powered dams (NPD) are classified by energy potential in terms of head. Low head facilities have design heads below 20 m and typically exhibit the following characteristics (DOE, 2016) :

- 1 MW to 10 MW

- New/rehabilitated intake structure

- Little, if any, new penstock

- Axial-flow or Kaplan turbines (2-4 units)

- New powerhouse (indoor)

- New/rehabilitated tailrace

- Minimal new transmission (< 5 miles, if required)

- Capacity factor of 35% to 60%.

High head facilities have design heads above 20 m and typically exhibit the following characteristics (DOE, 2016) :

- 5 MW to 30 MW

- New/rehabilitated intake structure

- New penstock (typically < 500 feet of steel penstock, if required)

- Francis turbines (1-3 units)

- New powerhouse (indoor)

- New/rehabilitated tailrace

- Minimal new transmission line (up to 15 MW, if required)

- Capacity factor of 35% to 60%.

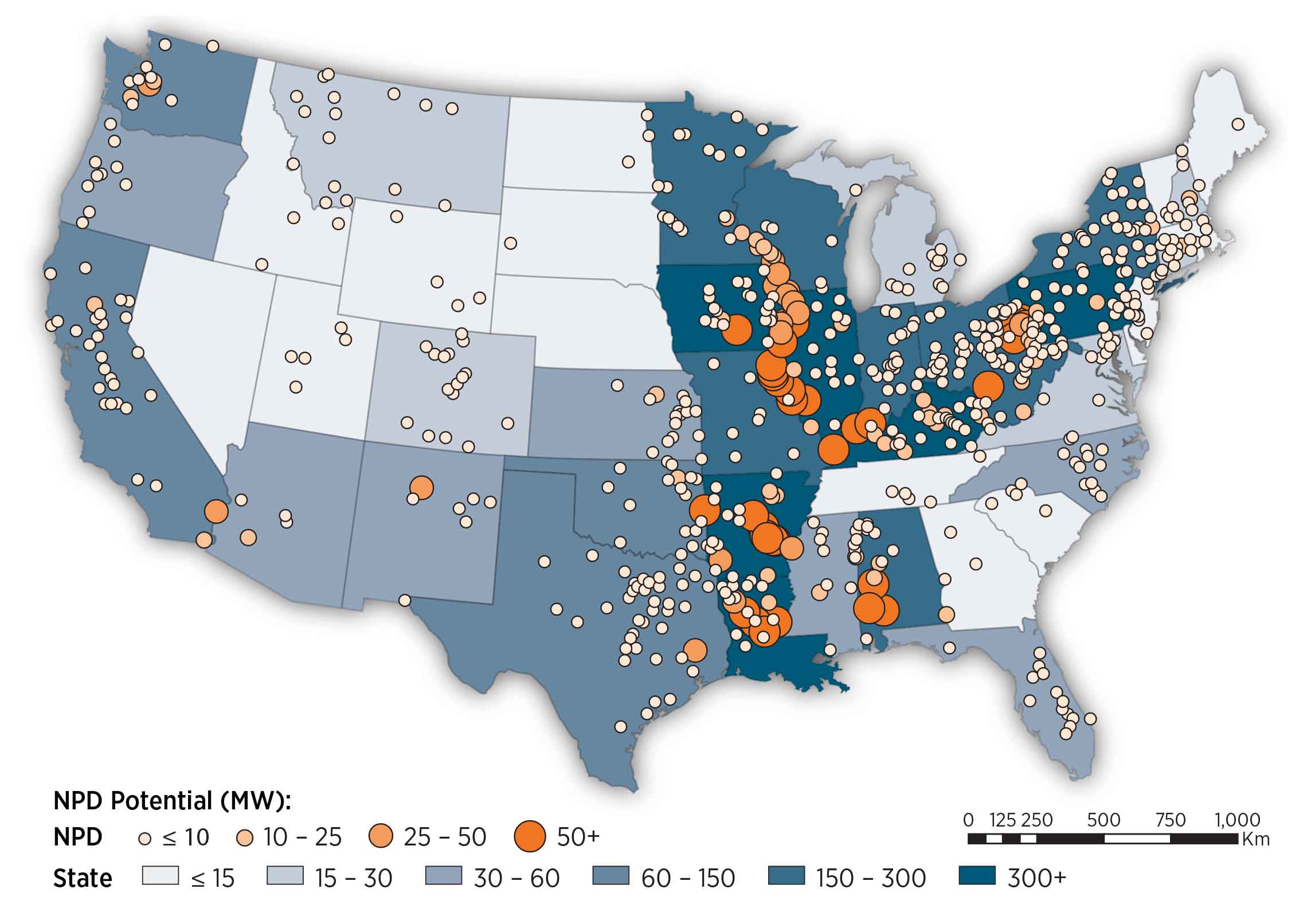

Resource Potential

Up to 12 GW of technical potential exists to add power to U.S. NPD. However, based on financial decisions in recent development activity, the economic potential of NPD may be approximately 5.6 GW at more than 54,000 dams in the contiguous United States. Most of this potential (5 GW or 90% of resource capacity) is associated with less than 700 dams. These resource considerations are discussed below:

According to the National

Inventory of Dams, more than 80,000 dams exist that do not produce

power. This data set was filtered to remove dams with erroneous flow

and geographic data and dams whose data could not be resolved to a

satisfactory level of detail

A new methodology for sizing potential hydropower facilities that was developed for the new-stream reach development resource (Kao et al., 2014) was applied to non-powered dams. This resource potential was estimated to be 5.6 GW at more than 54,000 dams. In the development of the Hydropower Vision, the NPD resource available to the ReEDS model was adjusted based on recent development activity and limited to only those projects with power potential of 500 kW or more. As the ATB uses the Hydropower Vision supply curves, this results in a final resource potential of 5 GW/29 TWh from 671 dams.

For each facility, a design capacity, average monthly flow rate over a 30-year period, and a design flow rate exceedance level of 30% are assumed. The exceedance level represents the fraction of time that the design flow is exceeded. This parameter can be varied and results in different capacity and energy generation for a given site. The value of 30% was chosen based on industry rules of thumb. The capacity factor for a given facility is determined by these design criteria.

Design capacity and flow rate dictate capacity and energy generation potential. All facilities are assumed sized for 30% exceedance of flow rate based on long-term, average monthly flow rates.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

Site-specific CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor estimates are made

for each site in the available resource potential. CAPEX and O&M

estimates are made based on statistical analysis of historical plant

data from 1980 to 2015

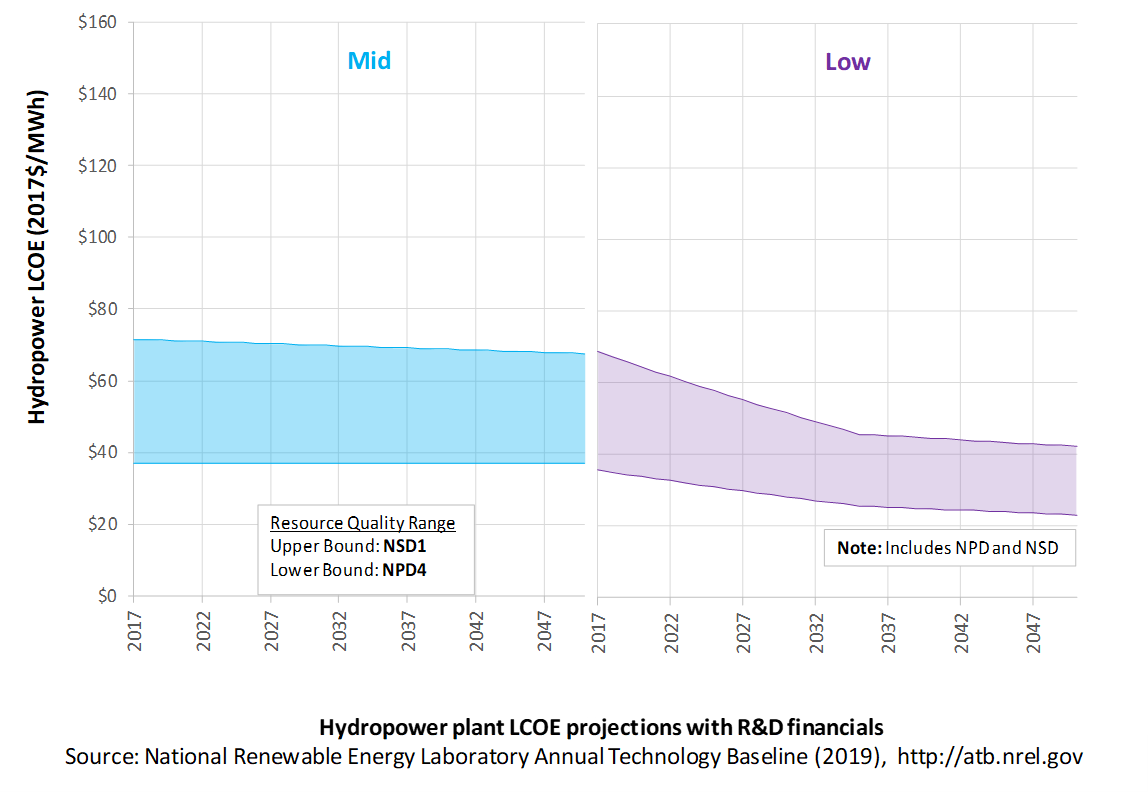

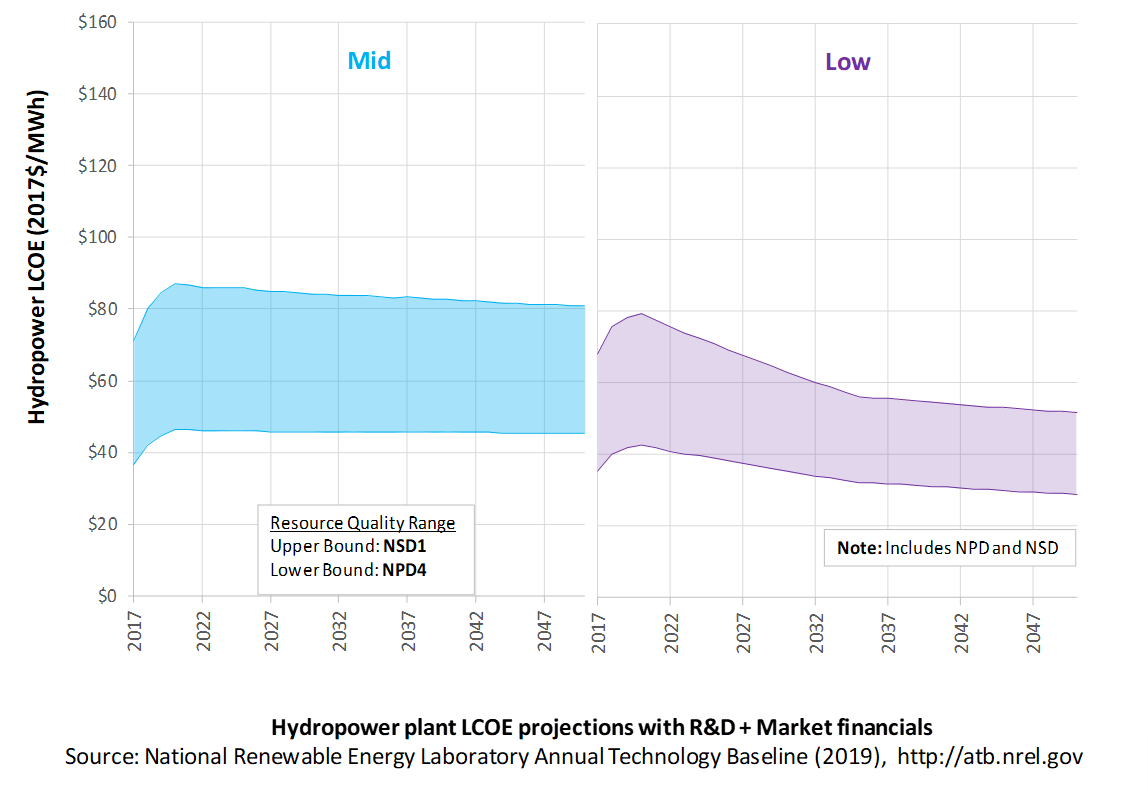

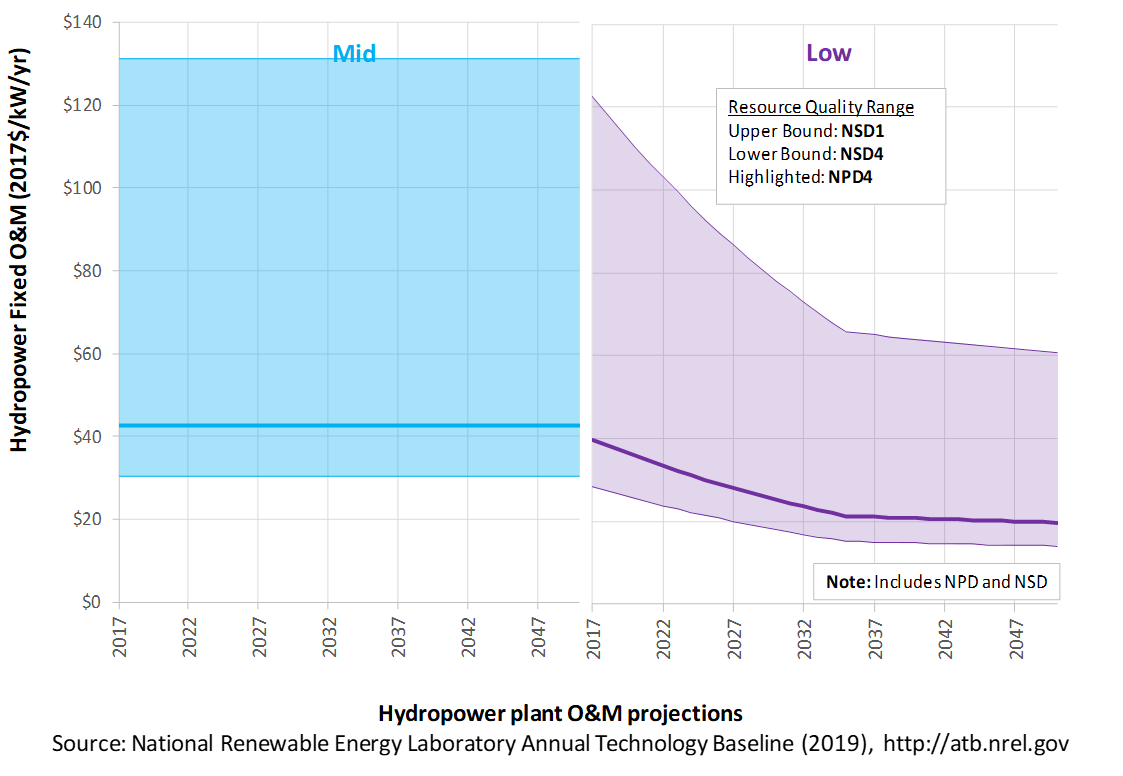

Projections developed for the Hydropower Vision study (DOE, 2016) using technological learning assumptions and bottom-up analysis of process and/or technology improvements provide a range of future cost outcomes. Three different projections were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: incremental technology learning, consistent with Reference in Hydropower Vision (DOE, 2016); CAPEX reductions for new stream-reach development (NSD) only

- Low cost: gains that are achievable when pushing to the limits of potential new technologies, such as modularity (in both civil structures and power train design), advanced manufacturing techniques, and materials, consistent with Advanced Technology in Hydropower Vision (DOE, 2016); both CAPEX and O&M cost reductions implemented.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model includes a sensitivity scenario that restricts the resource potential to sites greater than 500 kW, consistent with the Hydropower Vision, which results in 5 GW/29 TWh at 671 dams.

Representative Technology

Greenfield or new stream-reach development (NSD) sites are defined as new hydropower developments along previously undeveloped waterways and typically exhibit the following characteristics (DOE, 2016) :

- 1 MW to 100 MW

- New diversion/intake structure

- New penstock

- Steel with length being head/terrain dependent

- Various turbine selections

- Impulse/Francis are common for recently completed projects

- New powerhouse (indoor)

- New tailrace

- New transmission line (up to 15 miles for new projects)

- 30% to 80% capacity factor.

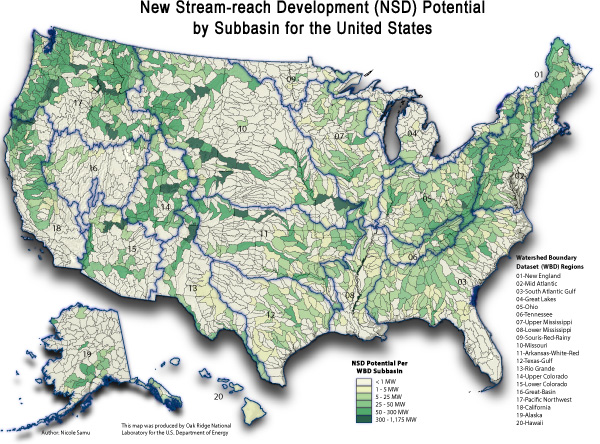

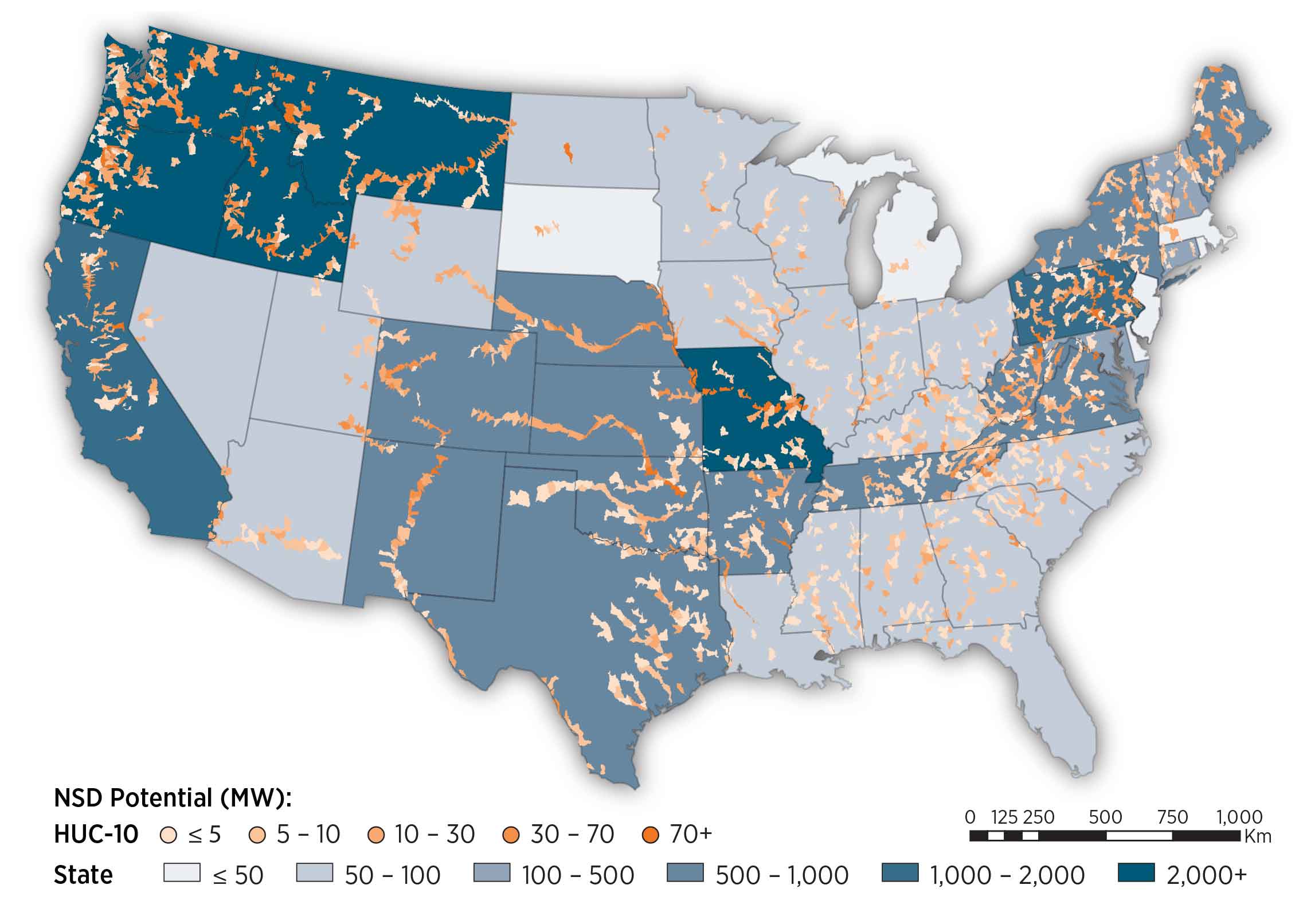

Resource Potential

The resource potential is estimated to be 53.2 GW/301 TWh at nearly 230,000 individual sites (Kao et al., 2014) after accounting for locations statutorily excluded from hydropower development such as national parks, wild and scenic rivers, and wilderness areas.

About 8,500 stream reaches were evaluated to assess resource potential (i.e., capacity) and energy generation potential (i.e., capacity factor). For each stream reach, a design capacity, average monthly flow rate over a 30-year period, and design flow rate exceedance level of 30% are assumed. The exceedance level represents the fraction of time that the design flow is exceeded. This parameter can be varied and results in different capacity and energy generation for a given site. The value of 30% was chosen based on industry rules of thumb. The capacity factor for a given facility is determined by these design criteria. Plant sizes range from kilowatt-scale to multi-megawatt scale (Kao et al., 2014) .

The resource assessment approach is designed to minimize the footprint of a hydropower facility by restricting inundation area to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 100-year floodplain.

New hydropower facilities are assumed to apply run-of-river operation strategies. Run-of-river operation means the flow rate into a reservoir is equal to the flow rate out of the facility. These facilities do not have dispatch capability.

Design capacity and flow rate dictate capacity and energy generation potential. All facilities are assumed sized for 30% exceedance of flow rate based on long-term, average monthly flow rates.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

Site-specific CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor estimates are made

for each site in the available resource potential. CAPEX and O&M

estimates are made based on statistical analysis of historical plant

data from 1980 to 2015

Projections developed for the Hydropower Vision study (DOE, 2016) using technological learning assumptions and bottom-up analysis of process and/or technology improvements provide a range of future cost outcomes. Three different projections were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: incremental technology learning, consistent with Reference in Hydropower Vision (DOE, 2016); CAPEX reductions for NSD only

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: gains that are achievable

when pushing to the limits of potential new technologies, such as

modularity (in both civil structures and power train design), advanced

manufacturing techniques, and materials, consistent with Advanced

Technology in Hydropower Vision

(DOE, 2016) ; both CAPEX and O&M cost reductions implemented.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model includes a sensitivity scenario that restricts the resource potential to sites greater than 1 MW, which results in 30.1 GW/176 TWh on nearly 8,000 reaches.

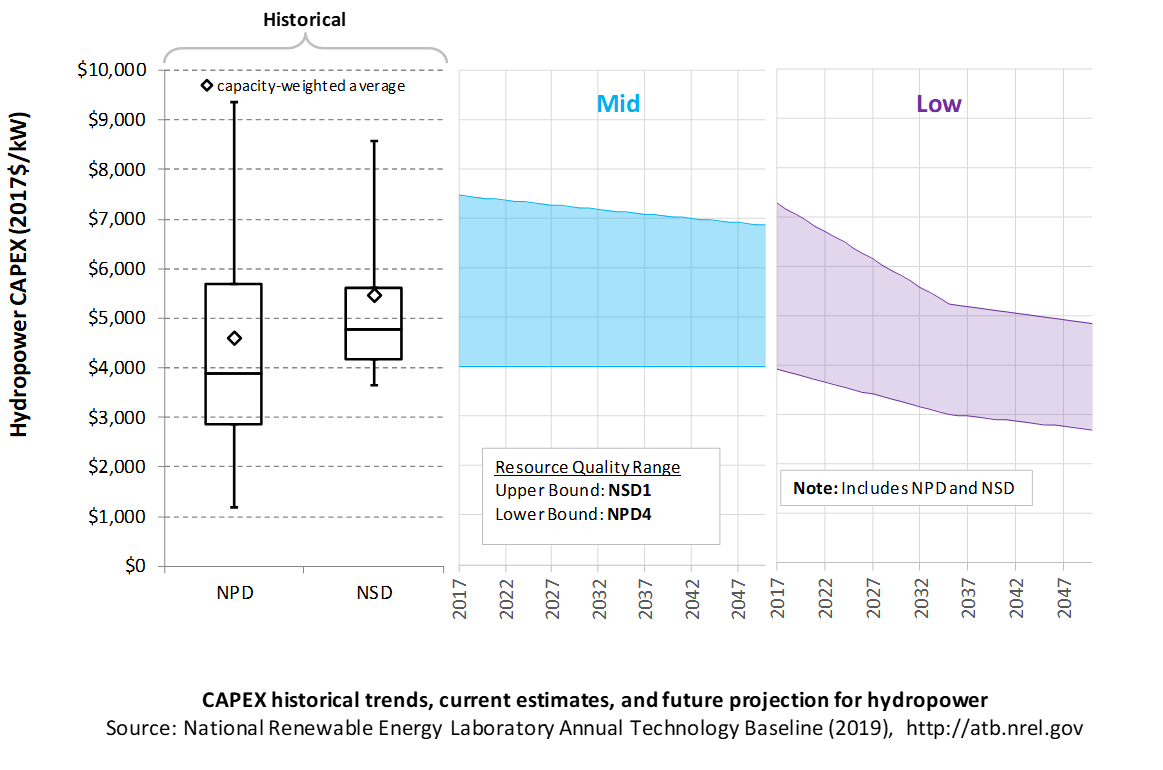

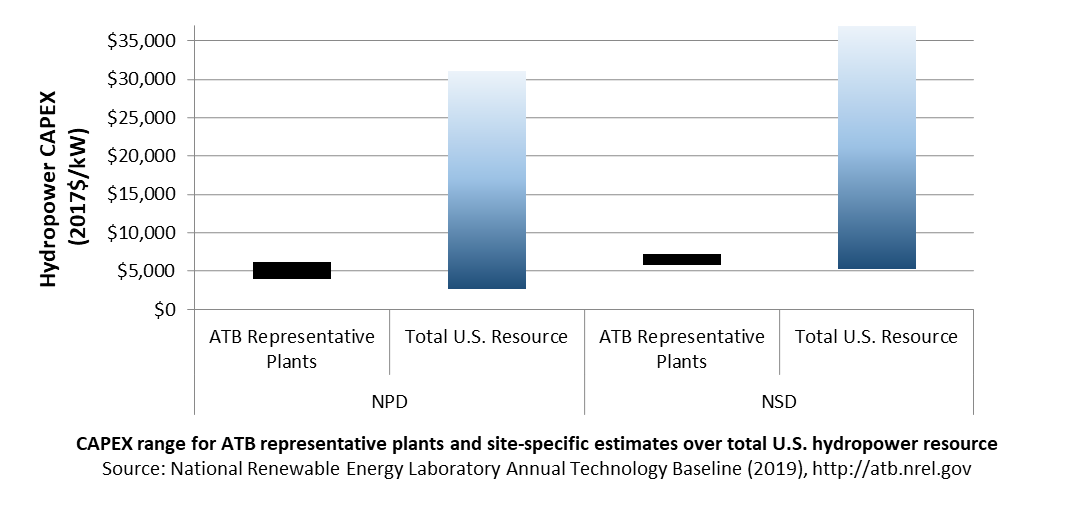

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the hydropower generation plant, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses regional CAPEX adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with resource in the contiguous United States.

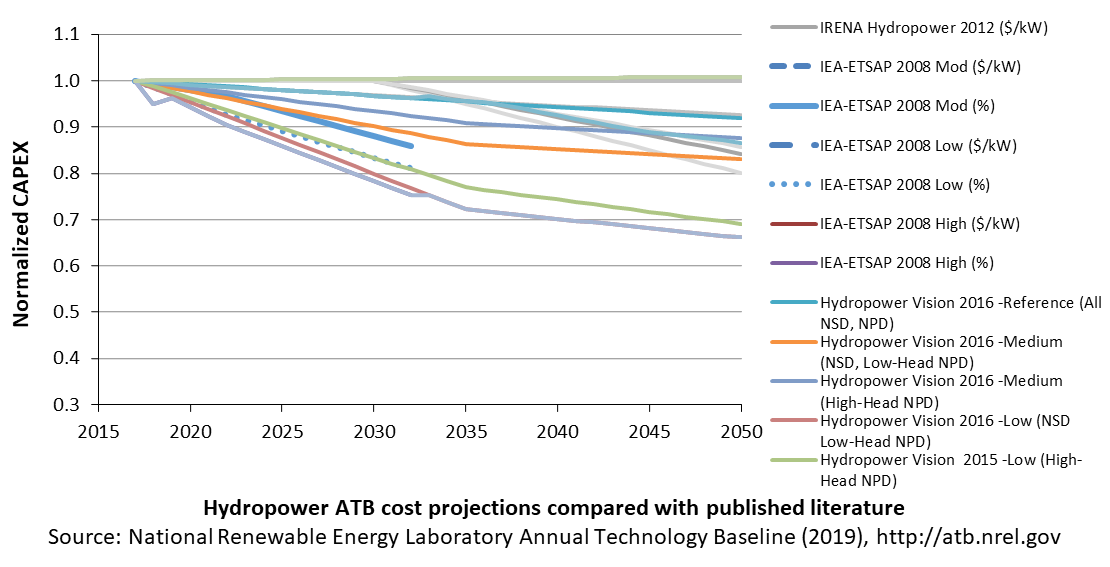

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs. Mid and Low technology cost scenarios are shown. Historical data from actual and proposed non-powered dam (NPD) and new stream-reach development (NSD) plants installed in the United States from 1981 to 2014 are shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Recent Trends

Actual and proposed NPD and NSD CAPEX from 1981 to 2014

The higher-cost ATB sites generally reflect small-capacity, low head sites that are not comparable to the historical data sample's generally larger-capacity and higher head facilities. These characteristics lead to higher ATB Base Year CAPEX estimates than past data suggest. For example, the NSD projects that became commercially operational in this period are dominated by a few high head projects in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest or Alaska.

The Base Year estimates of CAPEX for NPDs in the ATB range from $3,800/kW to $6,000/kW. These estimates reflect facilities with 3 feet of head to more than 60 feet of head and from 0.5 MW to more than 30 MW of capacity. In general, the higher-cost sites reflect much smaller-capacity (< 10 MW), lower head (< 30 ft.) sites that have fewer analogues in the historical data, but these characteristics result in higher CAPEX.

The Base Year estimates of CAPEX for NSD range from $5,500/kW to $7,900/kW. The estimates reflect potential sites with 3 feet of head to more than 60 feet head and from 1 MW to more than 30 MW of capacity. In general, NSD potential represents smaller-capacity facilities with lower head than most historical data represent. These characteristics lead to higher CAPEX estimates than past data suggest, as many of the larger, higher head sites in the United States have been previously developed.

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, all potential NPD and NSD sites were first binned by both head and capacity. Analysis of these bins provided groupings that represent the most realistic conditions for future hydropower deployment. The design values of these four reference NPD and four reference NSD plants are shown below. The full range of resource and design characteristics is summarized in the ATB data spreadsheet.

Representative Hydropower Plants

| Resource Characteristics Ranges | Weighted Average Values | Calculated Plant Values | |||||

| Plants | Head (feet) | Capacity (MW) | Head (feet) | Capacity (MW) | Capacity Factor | ICC (2014$/kW) | O&M (2014$/kW) |

| NPD 1 | 3-30 | 0.5-10 | 15.4 | 4.8 | 0.62 | 5,969.33 | 111.73 |

| NPD 2 | 3-30 | 10+ | 15.9 | 82.2 | 0.64 | 5,433.24 | 30.74 |

| NPD 3 | 30+ | 0.5-10 | 89.6 | 4.2 | 0.60 | 3,997.79 | 118.67 |

| NPD 4 | 30+ | 10+ | 81.3 | 44.7 | 0.60 | 3,769.22 | 40.54 |

| NSD 1 | 3-30 | 1-10 | 15.7 | 3.7 | 0.66 | 7,034.81 | 125.01 |

| NSD 2 | 3-30 | 10+ | 19.6 | 44.1 | 0.66 | 6,280.15 | 40.76 |

| NSD 3 | 30+ | 1-10 | 46.8 | 4.3 | 0.62 | 6,151.05 | 117.61 |

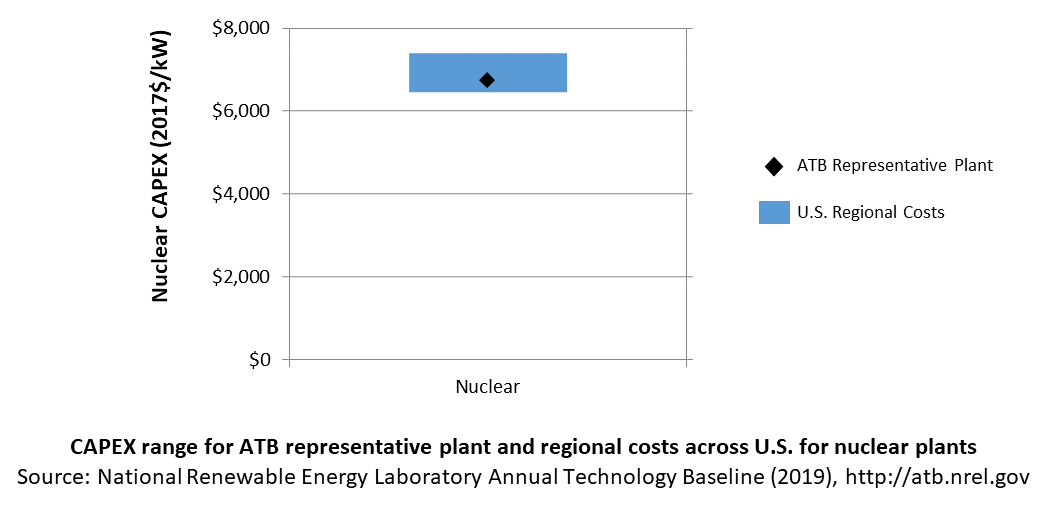

| NSD 4 | 30+ | 10+ | 45.3 | 94.0 | 0.66 | 5,537.34 | 28.93 |