2019 ATB

For each electricity generation technology in the ATB, this website provides:

- Capital expenditures (CAPEX): the definition of CAPEX used in the ATB and the historical trends, current estimates, and future projections of CAPEX used in the ATB

- Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs: the definition of O&M and the current estimates and future projections of O&M used in the ATB

- Capacity factor (CF): the definition of CF and the historical trends, current estimates, and future projections of CF used in the ATB

- Future cost and performance methods: an outline of the methodology used to make the projections of future cost and performance in the ATB for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases

- Levelized cost of energy (LCOE): metric that combines CAPEX, O&M, CF, and projections for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases for illustration of the combined effect of the primary cost and performance components and discussion of technology advances that yield future projections

- Financing assumptions: development of technology-specific interest rate on debt, return on equity, and debt-to-equity ratios and their impact on LCOE are documented in each technology section, where applicable, and summarized here.

Electricity generation technologies are selected on the left side of the screen, and the topics highlighted above can be selected using the drop-down menu at the top right of the screen.

Guidelines for using and interpreting ATB content and comparisons to other literature are provided. LCOE accounts for many variables important to determining the competitiveness of building and operating a specific technology (e.g., upfront capital costs, capacity factor, and cost of financing); however, it does not necessarily demonstrate which technology in a given place and time would provide the lowest cost option for the electricity grid. Such analysis is performed using electric sector models such as the Regional Energy Deployment Systems (ReEDS) model and corresponding analysis results such as the NREL Standard Scenarios.

The NREL Standard Scenarios, a companion product to the ATB, provides a suite of electric sector scenarios and associated assumptions, including technology cost and performance assumptions from the ATB.

ATB data sources and references are also provided for each technology. All dollar values are presented in 2017 U.S. dollars, unless noted otherwise.

Additional information is available here: About the 2019 ATB.

Land-Based Wind

The 2019 ATB characterization for land-based wind updates the Base Year and future wind technology cost and performance estimates from years past to align with current expectations for wind energy costs over the coming decades. This year's ATB characterization for land-based wind relies on a new bottoms-up engineering approach for 2030 turbine and plant technology that is used to inform cost and performance characterizations through 2030. This new approach was developed based on persistent feedback since the release of the Wind Vision report (DOE & NREL, 2015) and the System Management of Atmospheric Resource through Technology (SMART) strategies wind plant analysis (Dykes et al., 2017) , from the wind industry original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and stakeholder community that noted the wind ATB mid case assumptions to be overly conservative. Based on this feedback and observations of substantial technology gains in recently commercialized turbine offerings an array of industry experts now anticipate wind energy LCOEs of 2-2.5 cent/kWh by the mid-2020s, depending on specific financing terms and conditions. In terms of technology gains, the most noteworthy has been the substantial and rapid scaling of wind turbines from the 2-MW to 4-MW with increases in rotor size from approximately 100 m to 150 m. These gains in scale are allowing modern technology to capture turbine level economies of scale and balance of plant efficiencies while placing the turbine in better resource regimes at greater heights above ground level.

To better align with the OEM and industry stakeholder cost reduction expectations NREL redefined the methodology used for estimating future energy costs. Specifically, for this year's ATB NREL used expert input to define one of many potential turbine technology pathways for a Mid and Low scenario in 2030. Bottom-up engineering cost and performance analysis were then executed to obtain the future cost reduction trajectories (Stehly, Beiter, Heimiller, & Scott, 2020) . Although this method has resulted in a cost reduction pathway that maintains and could even accelerate recent significant cost reduction gains, these results are believed to be more in line with wind industry analyst and OEM expectations. There is substantial focus throughout the global wind industry on driving down costs and increasing performance due to fierce competition from within as well as among several power generation technologies including solar PV and natural gas-fired generation.

Representative Technology

Representative technologies for land-based wind for the base year (2017) and 2030 assume a 50-MW to 100-MW facility, consistent with current project sizes (Wiser & Bolinger, 2018) . Our base year characterization is extracted from wind turbines installed in the United States in 2017 which were, on average, 2.3-MW turbines with rotor diameters of 113 m and hub heights of 86 m (Wiser & Bolinger, 2018) . Our 2030 representative technology assumes a 4.5-MW turbine with a rotor diameter of 167 m and a hub height of 110 m. Notably turbines that are nearly of this scale (i.e., 4-MW, 150 m rotor and 80-m to 110-m hub height are commercially available today and expected to be installed in facilities in the U.S. in the early 2020s.

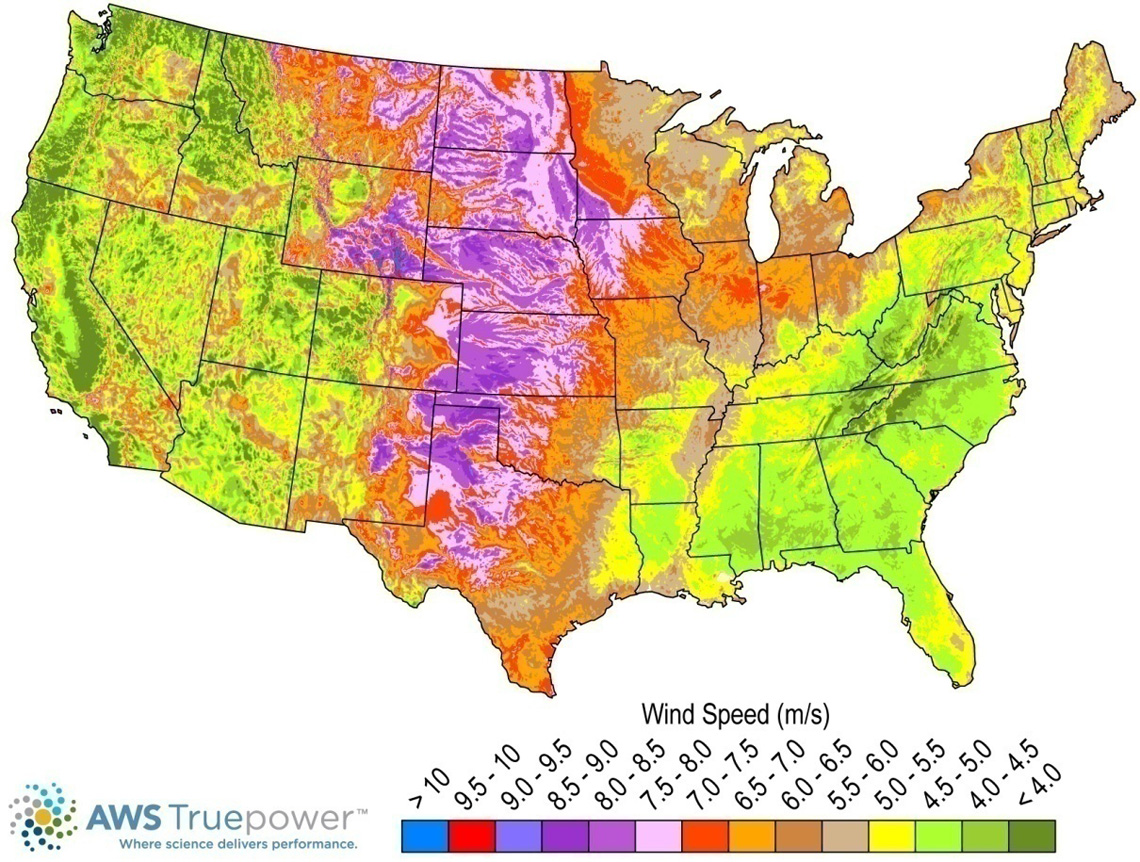

Resource Potential

Wind resource is prevalent throughout the United States but is concentrated in the central states. Total land-based wind technical potential exceeds 10,000 GW (almost tenfold current total U.S. electricity generation capacity), which would use the wind resource on 3.5 million km2 of land area but would disrupt or exclude other uses from a fraction of that area. This technical potential does not include standard exclusions-lands such as federally protected areas, urban areas, and water. Resource potential has been expanded from approximately 6,000 GW (DOE & NREL, 2015) by including locations with lower wind speeds to provide more comprehensive coverage of U.S. land areas where future technology may improve economic potential.

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012) , represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential, including resource, technical, economic, and market potential (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

The resource potential is calculated by using more than 130,000 distinct areas for wind plant deployment that cover more than 3.5 million km2. The potential capacity is estimated to total more than 10,000 GW if a power density of 3 MW/km2 is assumed.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

For each of the 130,000 distinct areas, an LCOE is estimated taking into consideration site-specific hourly wind profiles. Representative wind turbines derived from annual installation statistics are associated with a range of average annual wind speed based on actual historical wind plant installations. This method is described by Moné (2017) and summarized below:

- Capital expenditures (CAPEX) associated with wind plants installed in the interior of the country are used to characterize CAPEX for hypothetical wind plants with average annual wind speeds that correspond with the median conditions for recently installed wind facilities.

- Capacity factor is determined for each unique location using the site-specific hourly wind profile and a power curve that corresponds with the representative wind turbine defined to represent the annual average wind speed for each site.

- Average annual operations and maintenance (O&M) costs are assumed to be equivalent at all geographic locations.

- LCOE is calculated for each area based on the CAPEX and capacity factor estimated for each area.

For representation in the ATB, the full resource potential, reflecting the 130,000 individual areas, was divided into 10 techno-resource groups (TRGs). The capacity-weighted average CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor for each group is presented in the ATB. ATB Base Year costs for land-based wind are calibrated to NREL's 2017 Cost of Wind Energy Review (Stehly, Beiter, Heimiller, & Scott, 2018).

Focusing on future costs, this year's ATB characterization represents an update relative to years past in order to realign with current expectations for costs over the next decade. Three different projections were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: 2030 cost estimates for the Mid scenario are estimated (1) using NREL's Cost and Scaling Model (CSM) and inputs from analyst-predicted turbine and plant technology in 2030 specific to the Mid case (Stehly et al., 2020) and (2) applying technology-specific cost adjustments for factors such as construction contingencies and transportation. Beyond 2030, costs and performance were derived from an estimated change in LCOE from 2030 to 2050 based on historical land-based wind LCOE and single-factor learning rates ranging from 10.5% to 18.6%, meaning LCOE declines by this amount for each doubling of global cumulative wind capacity (Wiser et al., 2016) . NREL's Cost and Scaling applies component level scaling relationships (e.g., for the blades, hub, generator, and tower) that reflect the component-specific and often nonlinear relationship between size and cost (Christopher Moné et al., 2017) .

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: 2030 cost estimates for the Low scenario are estimated using NREL's CSM and inputs from the analyst-predicted turbine technology in 2030 specific to the Low case (Stehly et al., 2020) and applying technology-specific cost adjustments; beyond 2030, the costs were derived using the same learning rate methodology as for the Mid case but assuming an increase in global cumulative capacity.

In last year's ATB, the mid case cost projections were informed by the expert survey that reported expected LCOE changes in percentage terms relative to 2014 baseline values (Wiser et al., 2016) . Prior mid case projections were estimated using the entire sample size from the survey work (163 experts) which included strategic, system-level thought leaders with wind technology, costs, and/or market expertise. However, the survey also identified a smaller group – deemed "leading experts" through a deliberative process by a core group of International Energy Agency (IEA) Wind Task 26 members. This leading experts group (22 leading experts) generally expected more aggressive wind energy cost reductions. Recent wind industry data focused on price points more than 3-5 years into the future indicate that costs are falling more quickly than the full sample predicted and more in line with the leading Experts predictions. This year's ATB mid case is informed both by this leading group of experts' predictions as well as the expert input and bottom-up engineering pathways analysis referenced previously.

The Low case is primarily informed by the wind program's Atmosphere to Electrons (A2e) applied research initiative that advances the fundamental science necessary to drive innovation and the realization of the SMART wind power plant of the future (Dykes et al., 2017) . This research in addition to ongoing Wind Energy Technologies Office (WETO) projects including Big Adaptive Rotors (DOE, 2018) , Lightweight Drivetrains (DOE EERE, 2019) , and Tall Towers (2019 Wind Energy Technologies Office Funding Opportunity Announcement, 2019) support the wind industry's ongoing scaling activities and manufacturing improvements and were combined to assess additional potential pathways and related projected cost impacts for each LCOE component.

As done in the expert survey work (Wiser et al., 2016) historical LCOE estimates were compared to the LCOE projections of the Mid and Low scenarios. The LCOE projections were found to require continued sizable cost reductions consistent with and potentially somewhat greater than the historical LCOE trends. Possible justifications for maintaining recent rates of high cost reduction and potentially even going beyond long-term historical LCOE learning include stiff competition from around the globe as well as a highly capitalized industry with annual expenditures on the order of $100 billion. Accordingly, the revised Mid scenario is now considered representative of the reference case for land-based wind. The Low cost scenario projections are derived from the same methodology as the Mid case but applying additional cost reduction potentials from a collection of intelligent and novel technologies that comprise next-generation wind turbine and plant technology and characterized as System Management of Atmospheric Resource through Technology, or SMART strategies (Dykes et al., 2017) . In both scenarios, the overall LCOE reductions resulting from these analyses were used as the basis for the ATB projections. Accordingly, all three cost elements – CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor – should be considered together; individual cost element projections are derived.

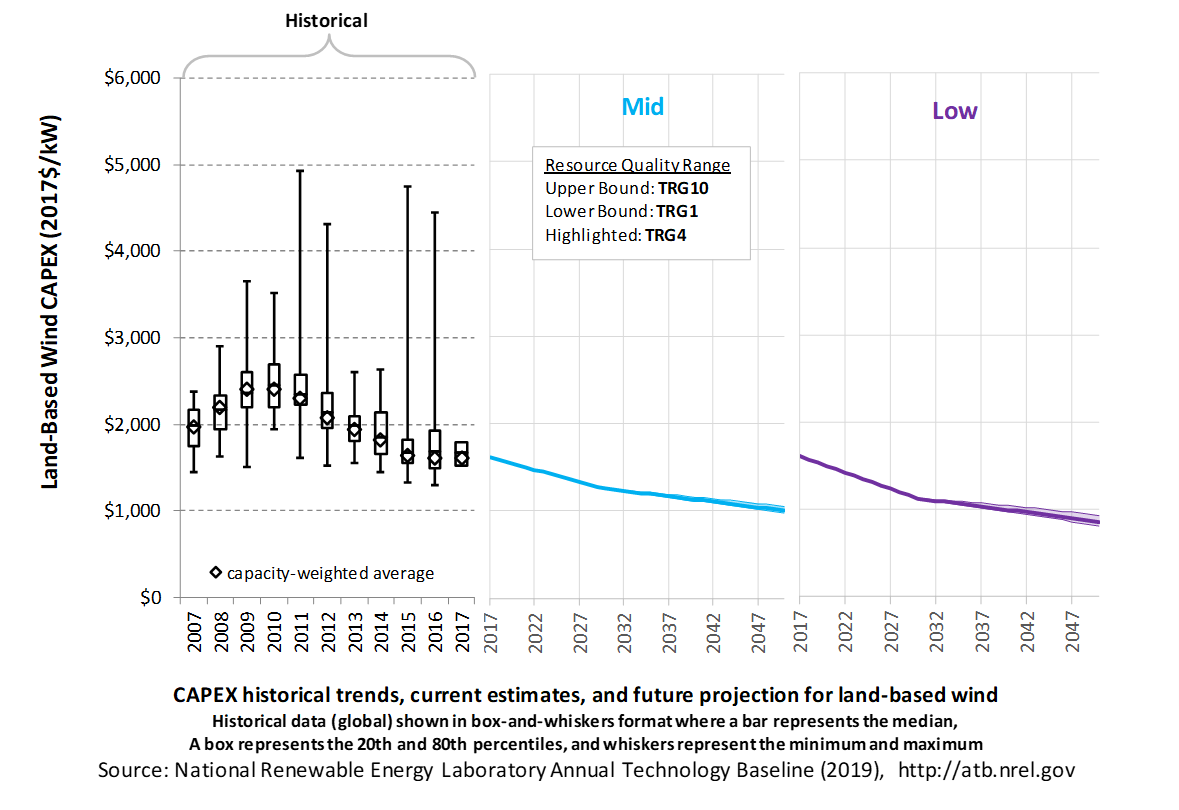

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the wind turbine, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with wind resource in the contiguous United States.

The CAPEX improvements for future land-based wind projects may be realized through many technology pathways to achieve LCOE reductions. It is also important to note that CAPEX improvements are not the only pathway to LCOE reductions as LCOE is also influenced by capacity factor, financing, O&M, and project life. For the purpose of reducing the vast combinations of future pathways NREL analysts defined a single future turbine configuration in 2030 to conduct the bottom-up cost analysis for the Mid and Low scenarios. The specific 2030 turbine configuration for the Mid scenario assumes a nameplate capacity of 4.5 MW with a rotor diameter of 167 m placed on a 110 m tower. Additional turbine configurations explored that resulted in LCOEs that were within 10% (or less) of the current Mid scenario included turbines with nameplate capacity ratings of 3-MW and 4-MW, rotor diameters down to 150 m, and hub heights up to 140 m. The relatively low sensitivity of LCOE to these changes in turbine configuration is indicative of the array potential pathways and solutions to the LCOE values estimated in this year's ATB.

The defined turbine characteristics were then used to estimate the total system CAPEX of a theoretical commercial scale (e.g., 100-MW) project. Although the relatively low observed sensitivity to significantly different turbine configurations for a single reference site indicate some uncertainty need for and value of wind turbine tailoring for varied site conditions, it is generally expected that over the long-term wind turbine designs will be optimized for a specific plant's site conditions. In this year's ATB, this site-specific design optimization process which is often reflected in different CAPEX values across TRGs was not included. Instead we assumed the single turbine configuration across all 10 TRGs. This simplification was applied due to limited resources and lack of necessary data to robustly characterize CAPEX variation across the 10 TRGs. Nevertheless, the ability to assess and tailor turbine configurations and CAPEX estimates for each TRG is expected to be reimplemented in future iterations of the ATB.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

For the ATB, and based on a capital cost estimates report from EIA (2016) and the System Cost Breakdown Structure defined by Moné et al. (2015), the wind plant envelope is defined to include:

- Wind turbine supply

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Turbine installation, substructure supply, and installation

- Site preparation, installation of underground utilities, access roads, and buildings for operations and maintenance

- Electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting turbines to each other and to the control center

- Project-related indirect costs, including engineering, distributable labor and materials, construction management start up and commissioning, and contractor overhead costs, fees, and profit.

- Financial costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Onsite electrical equipment (e.g., switchyard), a nominal-distance spur line (< 1 mile), and necessary upgrades at a transmission substation; distance-based spur line cost (GCC) not included in the ATB

- Interest during construction estimated based on three-year duration accumulated 10%/10%/80% at half-year intervals and an 8% interest rate (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., but the ReEDS model does include 134 regional multipliers (EIA, 2016).

The ReEDS model determines the land-based spur line (GCC) uniquely for each of the 130,000 areas based on distance and transmission line cost.

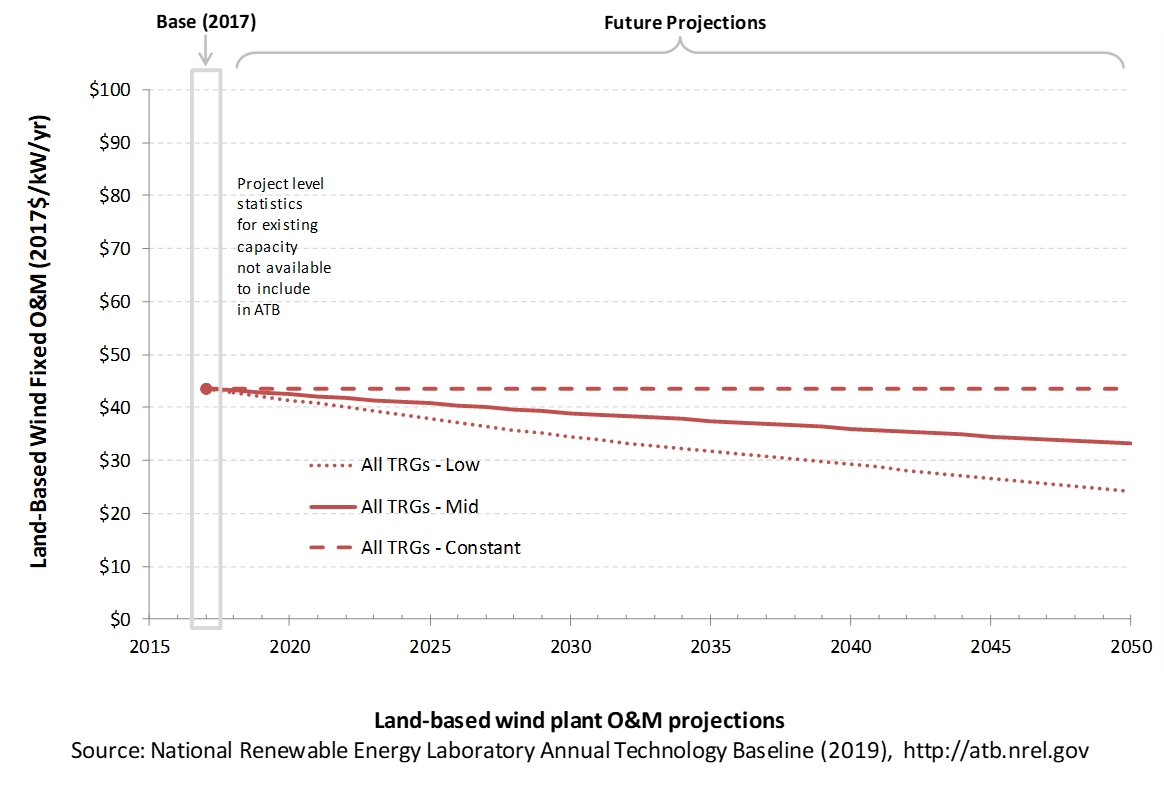

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs depend on capacity and represent the annual fixed expenditures required to operate and maintain a wind plant, including:

- Insurance, taxes, land lease payments, and other fixed costs

- Present value and annualized large component replacement costs over technical life (e.g., blades, gearboxes, and generators)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of wind plant components, including turbines and transformers, over the technical lifetime of the plant.

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed O&M (FOM) costs. Three cost scenarios are represented. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

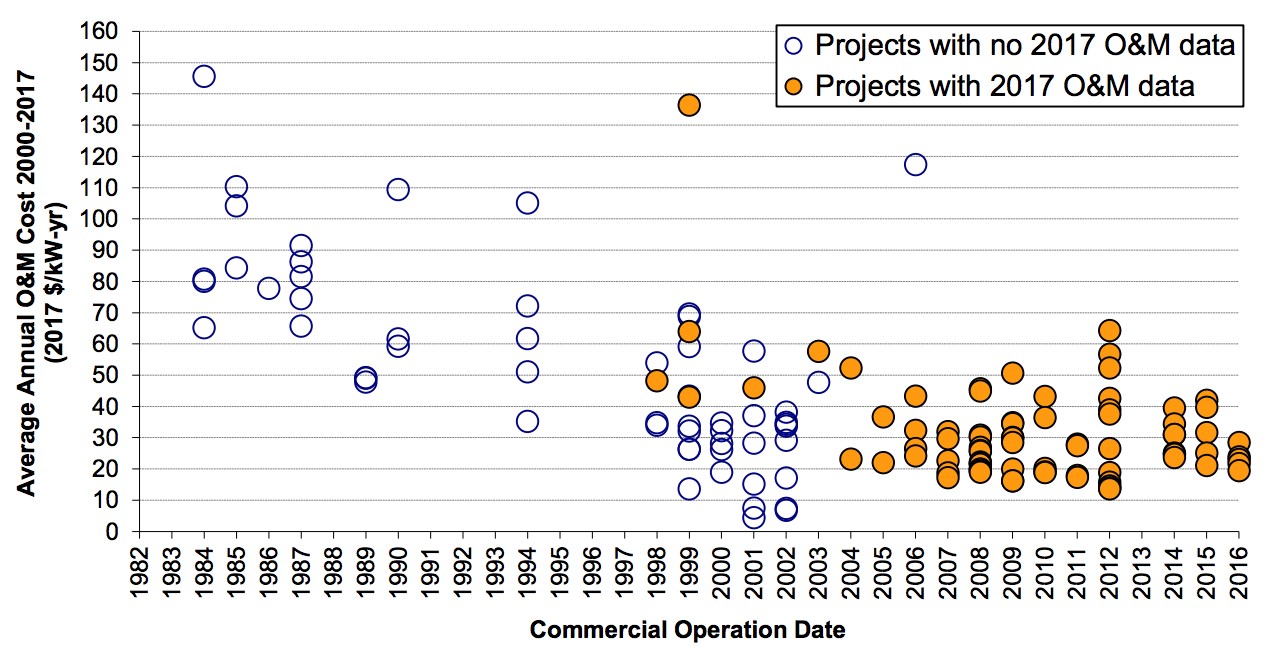

Base Year Estimates

The FOM of $44/kW-yr in the Base Year was estimated in the 2017 Cost of Wind Energy Review (Stehly, Beiter, Heimiller, & Scott, 2018); no variation of FOM with TRG (or wind speed) was assumed. The following chart shows sample historical data for reference.

Future Year Projections

Future FOM is assumed to decline by approximately 25% by 2050 in the Mid case and 45% in the Low case. These values are informed by recent work benchmarking work for wind power operating costs in the United States (Wiser, Bolinger, & Lantz, 2019).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

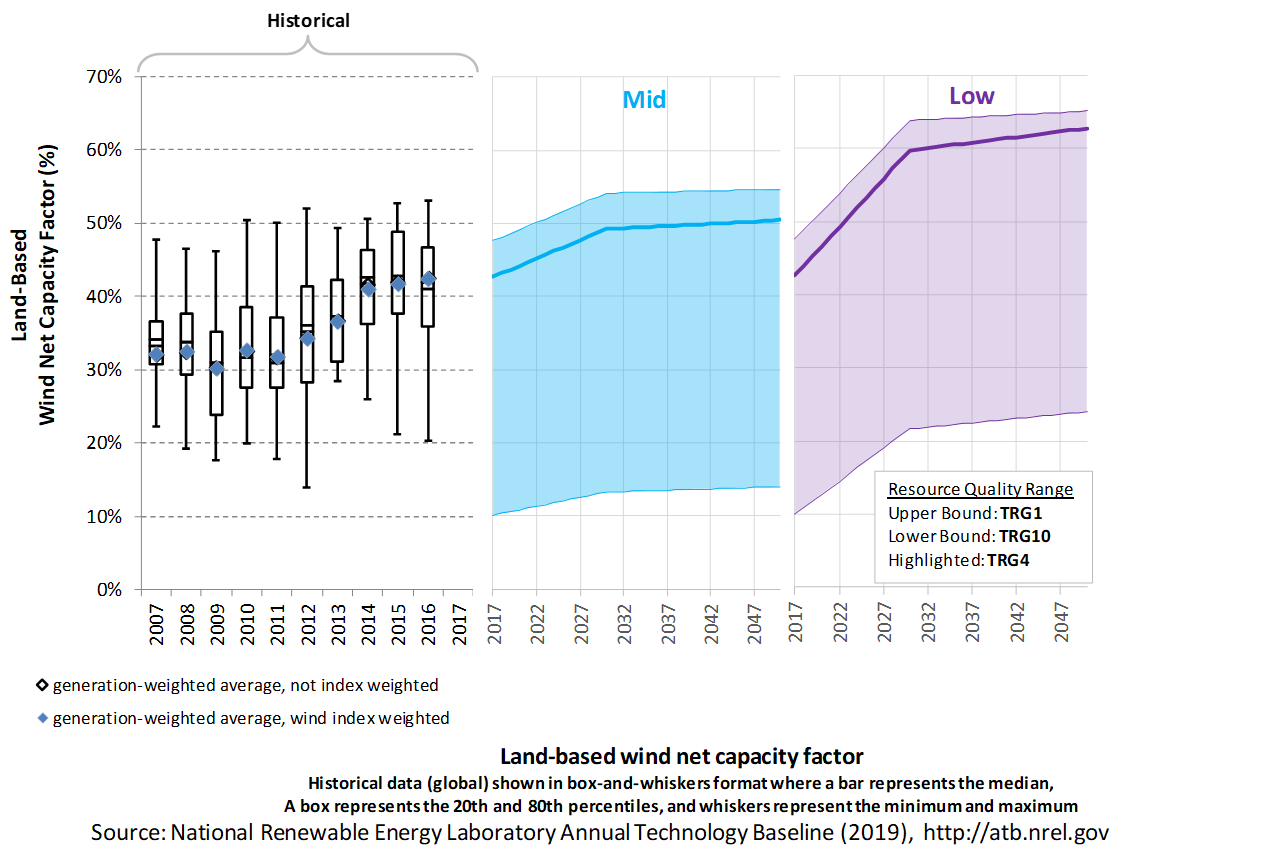

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

The capacity factor is influenced by hourly wind profile, expected downtime, and energy losses within the wind plant. The specific power (ratio of machine rating to rotor swept area) and hub height are design choices that influence the capacity factor.

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in the resource for wind plants in the contiguous United States. Historical data from wind plants operating in the United States in 2015, according to the year in which plants were installed, is shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The range of Base Year estimates illustrate the effect of locating a wind plant in sites with high wind speeds (TRG 1) or low wind speeds (TRG 10). Future projections are shown for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios.

Recent Trends

Actual energy production from about 90% of wind plants operating in the United States since 2007 is shown in box-and-whiskers format for comparison with the ATB current estimates and future projections. The historical data illustrate capacity factor for projects operating in 2017, shown by year of commercial online date. As reported in the 2017 DOE Wind Technologies Market Report (Wiser & Bolinger, 2018).

Base Year Estimates

Most installed U.S. wind plants generally align with ATB estimates for performance in TRGs 5-7. High wind resource sites associated with TRGs 1 and 2 as well as very low wind resource sites associated with TRGs 8-10 are not as common in the historical data, but the range of observed data encompasses ATB estimates.

To calculate the Base Year capacity factors the 2017 turbine characteristics (Wiser & Bolinger, 2018) are input into the System Advisor Model, or SAM and run for each of the weighted average wind speeds in each TRG.

The capacity factor is referenced to an 80-m, above-ground-level, long-term average hourly wind resource data from AWS Truepower (2012).

Future Year Projections

Projections for capacity factors implicitly reflect technology innovations such as larger rotors and taller towers that will increase energy capture at the same location (without specifying precise tower height or rotor diameter changes). Improvements in plant performance through lower losses and increased availability are also included implicitly. In practice future turbine designs will be optimized for a specific site with attempts to maximize capacity factor. This optimization is not captured in this analysis since one turbine configuration is defined for each of the TRGs. Analysts hope to enhance the ability to define site-specific turbine configurations for each TRG in future iteration of the ATB.

- Mid: The projected capacity factors in 2030 are calculated in SAM using the inputs of the predicted turbine technology in 2030 that are specific to the Mid scenario (Stehly et al., 2020) for each of the TRGs; additional wind plant performance and availability are also applied through technology innovations assessed in the SMART wind power plant of the future work (Dykes et al., 2017); beyond 2030, analysts predict generally modest improvements in wind plant performance through 2050 for the resource-rich site (i.e., TRGs 1 and 2) and increasing slightly for the less favorable resource sites (i.e., TRGs 8-10).

- Low: The projected capacity factors in 2030 are calculated in SAM using the inputs of the predicted turbine technology in 2030 that are specific to the Low scenario (Stehly et al., 2020) for each of the TRGs; additional wind plant performance and availability are also applied through technology innovations assessed in the SMART wind power plant of the future work (Dykes et al., 2017), but they assume further reduction in losses than in the Mid case; beyond 2030, analysts predict slightly higher improvements in wind plant performance than in the Mid case through 2050 for the resource-rich site (i.e., TRGs 1 and 2) and increasing slightly for the less favorable resource sites (i.e., TRGs 8-10).

Increased energy capture through turbine scaling and wind plant optimization are the two primary factors influencing wind plant capacity factor. The introduction of novel control mechanisms will continue to increase energy capture with more-precise control of the flow through the entire wind plant. These technology advancements are expected to increase capacity factor for all TRGs, with a more rapid rate of increases in capacity factor through 2030 and a slower rate of increase through 2050. This analysis is illustrative of one of many capacity factor improvement pathways for LCOE reduction. Of course, as was the case for CAPEX there are many different pathways to a given capacity factor. Turbine rotor diameter, specific power, and hub height can each be traded off to achieve a given capacity factor, depending on site conditions and relative costs for pursuing one approach or the other; plant layout and operational strategies that impact losses are additional levers that may be used to achieve a given capacity factor.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model output capacity factors for wind and solar PV can be lower than input capacity factors due to endogenously estimated curtailments determined by scenario constraints.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

ATB projections were derived from two different sources for the Mid and Low cases:

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: 2030 cost estimates for the Mid scenario are estimated (1) using CSM and inputs from analyst-predicted turbine technology in 2030 that are specific to the Mid case (Stehly et al., 2020) and (2) applying technology-specific cost adjustments; beyond 2030, the costs are derived from estimated change in LCOE from 2030 to 2050 based on historical land-based wind LCOE and single-factor learning rates ranging from 10.5% to 18.6%, meaning LCOE declines by this amount for each doubling of global cumulative wind capacity (Wiser et al., 2016). Future FOM is assumed to decline by approximately 25% by 2050 in the Mid case. These values are informed by recent work benchmarking work for wind power operating costs in the United States (Wiser et al., 2019). The projected capacity factors in 2030 are calculated in SAM using the inputs of the predicted turbine technology in 2030 that are specific to the Mid case (Stehly et al., 2020) for each of the TRGs; additional wind plant performance and availability are also applied through technology innovations assessed in the SMART wind power plant of the future work (Dykes et al., 2017); beyond 2030, analysts predict generally modest improvements in wind plant performance through 2050 for the resource-rich site (i.e., TRGs 1 and 2) and increasing slightly for the less favorable resource sites (i.e., TRGs 8-10).

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: 2030 cost estimates for the Low scenario are estimated (1) using NREL's CSM and inputs from the analyst-predicted turbine technology in 2030 that are specific to the Low case (Stehly et al., 2020) and (2) applying technology-specific cost adjustments; beyond 2030, the costs are derived using the same learning rate methodology as for the Mid case but assuming an increase in global cumulative capacity. Future FOM is assumed to decline by approximately 45% in the Low case. These values are informed by recent work benchmarking work for wind power operating costs in the United States (Wiser et al., forthcoming). The projected capacity factors in 2030 are calculated in SAM using the inputs of the predicted turbine technology in 2030 that are specific to the Low case (Stehly et al., 2020) for each of the TRGs; additional wind plant performance and availability are also applied through technology innovations assessed in the SMART wind power plant of the future work (Dykes et al., 2017), but they assume further reduction in losses than in the Mid case; beyond 2030, analysts predict slightly higher improvements in wind plant performance than in the Mid case through 2050 for the resource-rich site (i.e., TRGs 1 and 2) and increasing slightly for the less favorable resource sites (i.e., TRGs 8-10).

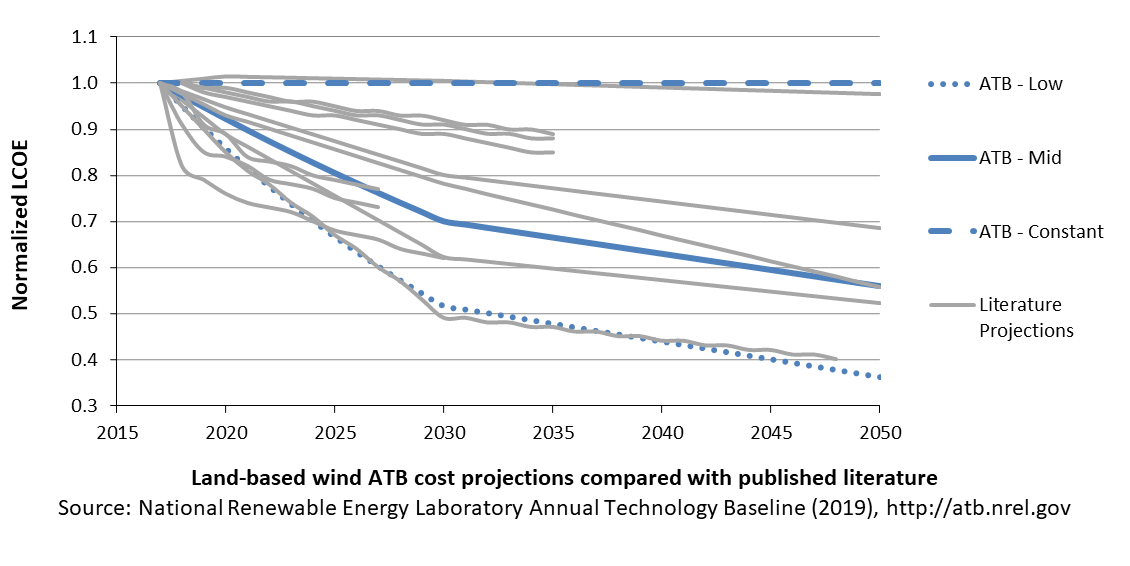

Projections of the cost of wind energy from the literature provide context for the ATB Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost projections. The ATB Mid cost projection results in LCOE reductions that are higher than other scenarios that are in median range of the literature ((Shreve, 2018), (BNEF, 2018)), and lower than ((Kost, Shammugam, Julch, Huyen-Tran, & Schlegl, 2018), (Wiser et al., 2016)). The ATB Low cost projection, which corresponds to the NREL bottom-up cost analysis, is relatively in line with the leading experts prediction (Wiser et al., 2016).

- Mid case projection institutions: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Wood Mackenzie, Global Wind Energy Council.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a summary metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

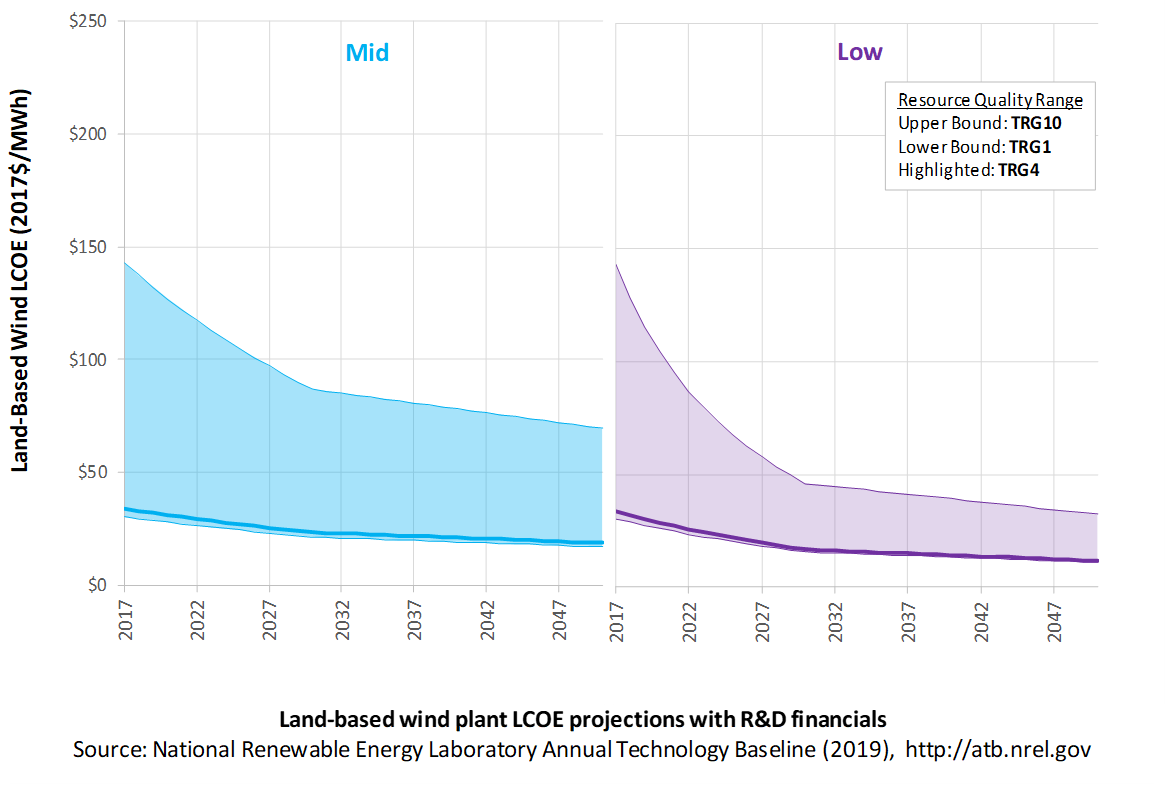

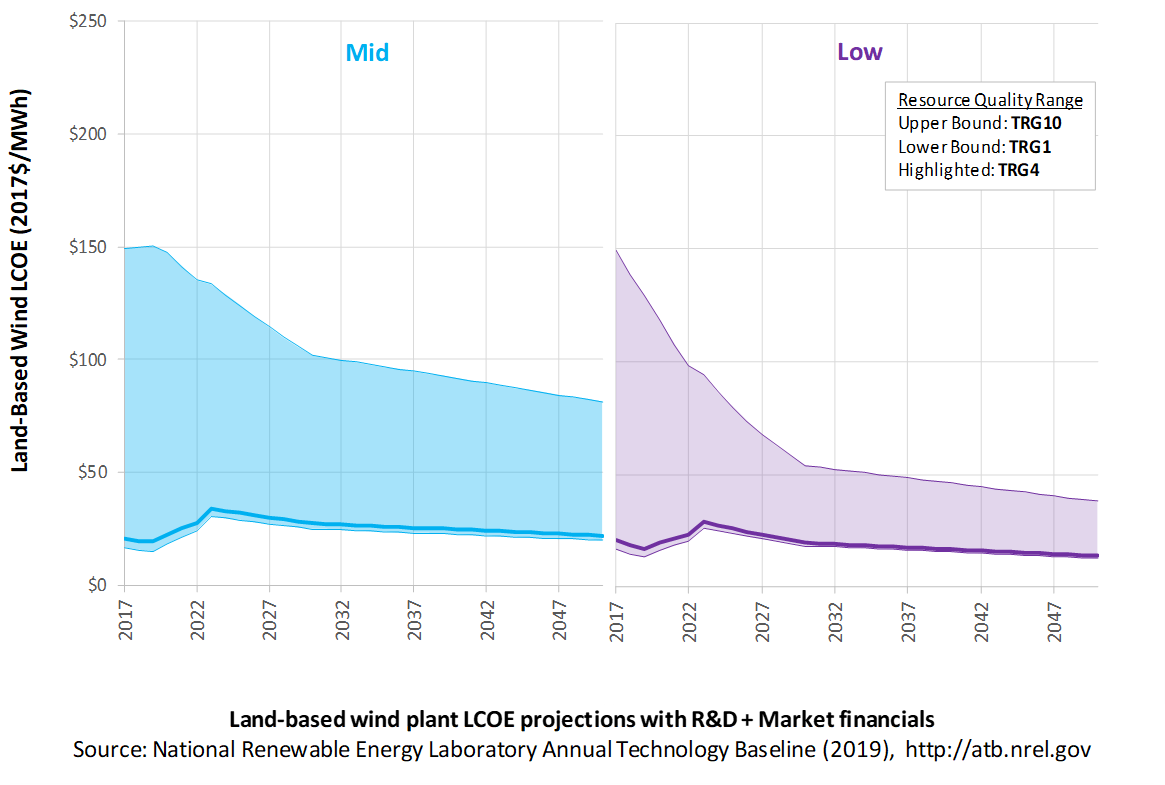

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for land-based wind across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs but not in the upfront capital costs (e.g., developer fees and contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside the United States, due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g., offshore wind in Europe) or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform and tax credits. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term land-based wind plants are associated with TRG 4. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA, 2019) and excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2019 (EIA, 2019) as well as effects of tax reform and tax credits. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE.

A constant cost recovery period – or period over which the initial capital investment is recovered – of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and it can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below.

- Continued turbine scaling to larger-megawatt turbines with larger rotors such that the swept area/megawatt capacity decreases, resulting in higher capacity factors for a given location

- Continued diversification of turbine technology whereby the largest rotor diameter turbines tend to be located in lower wind speed sites, but the number of turbine options for higher wind speed sites increases

- Taller towers that result in higher capacity factors for a given site due to the wind speed increase with elevation above ground level

- Improved plant siting and operation to reduce plant-level energy losses, resulting in higher capacity factors

- Wind turbine technology and plants that are increasingly tailored to and optimized for local site-specific conditions

- More efficient O&M procedures combined with more reliable components to reduce annual average FOM costs

- Continued manufacturing and design efficiencies such that capital cost/kilowatt decreases with larger turbine components

- Adoption of a wide range of innovative control, design, and material concepts that facilitate the above high-level trends.

Utility-Scale PV

Representative Technology

Utility-scale PV systems in the ATB are representative of one-axis tracking systems with performance and pricing characteristics in line with a 1.3 DC-to-AC ratio-or inverter loading ratio (ILR) (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018). PV system performance characteristics in previous ATB versions were designed in the ReEDS model at a time when PV system ILRs were lower than they are in current system designs; performance and pricing in the 2019 ATB incorporates more up-to-date system designs and therefore assumes a higher ILR.

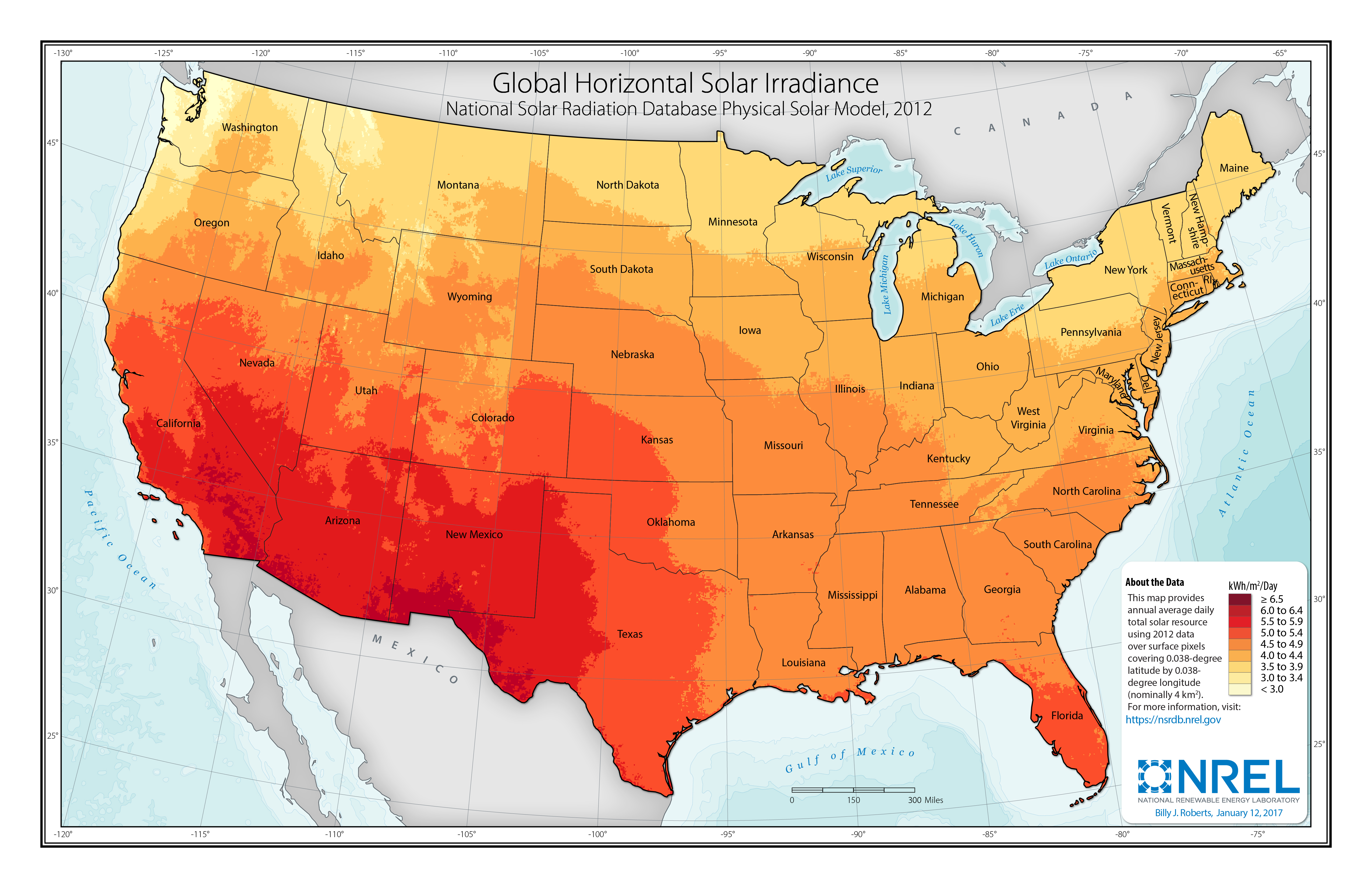

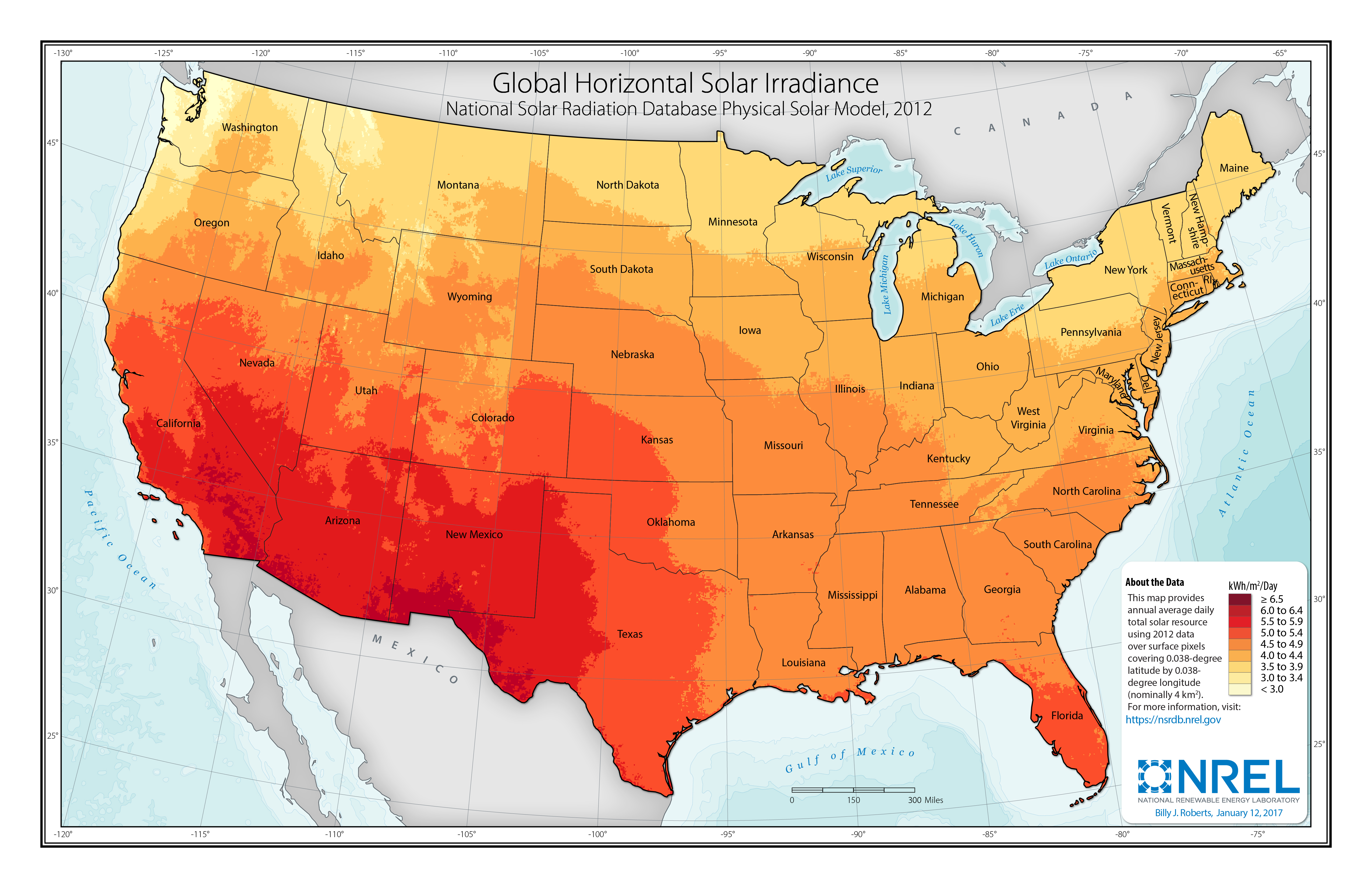

Resource Potential

Solar resources across the United States are mostly good to excellent at about 1,000-2,500 kWh/m2/year. The Southwest is at the top of this range, while Alaska and part of Washington are at the low end. The range for the contiguous United States is about 1,350-2,500 kWh/m2/year. Nationwide, solar resource levels vary by about a factor of two.

The total U.S. land area suitable for PV is significant and will not limit PV deployment. One estimate (Denholm and Margolis 2008) suggests the land area required to supply all end-use electricity in the United States using PV is about 5,500,000 hectares (ha) (13,600,000 acres), which is equivalent to 0.6% of the country's land area or about 22% of the "urban area" footprint (this calculation is based on deployment/land in all 50 states).

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012), represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential – resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

The Base Year estimates rely on modeled CAPEX and O&M estimates benchmarked with industry and historical data. Capacity factor is estimated based on hours of sunlight at latitude for five representative geographic locations in the United States. The ATB presents capacity factor estimates that encompass a range associated with Low, Mid, and Constant technology cost scenarios across the United States.

Future year projections are derived from analysis of published projections of PV CAPEX and bottom-up engineering analysis of O&M costs. Three different projections were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: based on the median of literature projections of future CAPEX; O&M technology pathway analysis

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: based on the low bound of literature projections of future CAPEX and O&M technology pathway analysis.

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

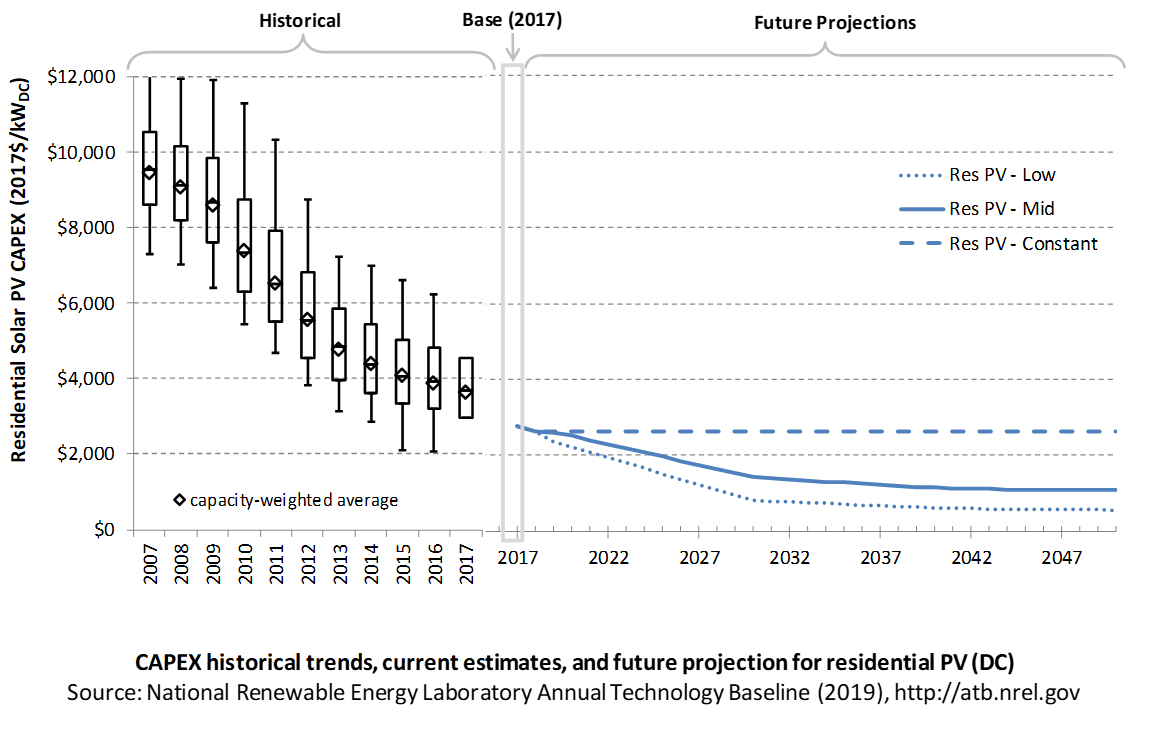

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the hardware, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with resource in the contiguous United States.

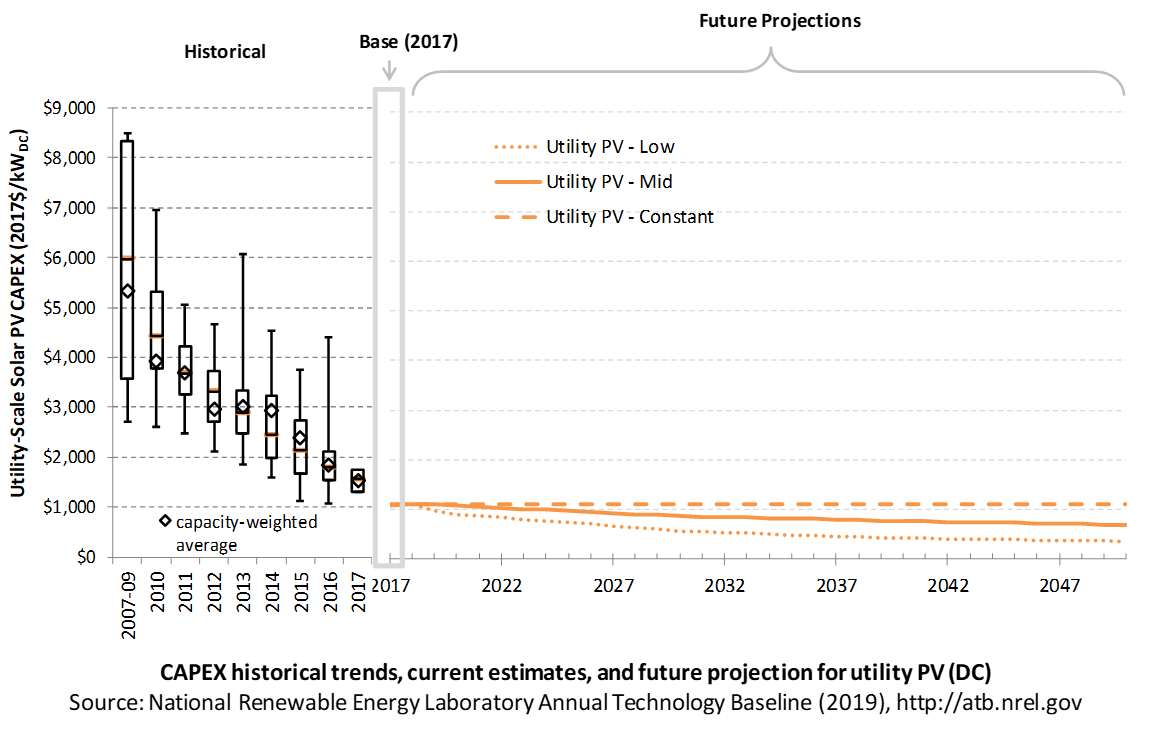

The following figures show the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs in terms of $/kWDC or $/kWAC. Three cost scenarios are represented: Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost. Historical data from utility-scale PV plants installed in the United States are shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

The PV industry typically refers to PV CAPEX in terms of $/kWDC based on the aggregated module capacity. The electric utility industry typically refers to PV CAPEX in terms of $/kWAC based on the aggregated inverter capacity. See Solar PV AC-DC Translation for details. The figures illustrate the CAPEX historical trends, current estimates, and future projections in terms of $/kWDC or $/kWAC; current estimates and future projections assume an inverter loading ratio of 1.3 while historical numbers represent reported values.

Recent Trends

Reported historical utility-scale PV plant CAPEX (Bolinger and Seel 2018) is shown in box-and-whiskers format for comparison to the historical benchmarked utility-scale PV plant overnight capital cost (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018) and future CAPEX projections. Bolinger and Seel (2018) provide statistical representation of CAPEX for 88% of all utility-scale PV capacity.

The difference in each year's price between the market and benchmark data reflects differences in methodologies. There are a variety of reasons reported and benchmark prices can differ, as enumerated by Barbose and Dargouth (2018) and Bolinger and Seel (2018) , including:

- Timing-related issues: For instance, the time between PPA contract completion date and project placed in service may vary, and a system can be reported as installed in separate sections over time or when an entire complex is complete. For example, in 2014, the reported capacity-weighted average system price was higher than 80% of system prices in 2014 due to very large systems, with multiyear construction schedules, installed in that year. Developers of these large systems negotiated contracts and installed portions of their systems when module and other costs were higher.

- Variations over time in the size, technology, installer margin, and design of systems installed in a given year

- Which cost categories are included in CAPEX (e.g., financing costs and initial O&M expenses).

Due to the investment tax credit, projects are encouraged to include as many costs incurred in the upfront CAPEX to receive a higher tax credit, which may have otherwise been reported as operating costs. The bottom-up benchmarks are more reflective of an overnight capital cost, which is in line with the ATB methodology of inputting overnight capital cost and calculating construction financing to derive CAPEX.

PV pricing and capacities are quoted in kWDC (i.e., module rated capacity) unlike other generation technologies, which are quoted in kWAC. For PV, this would correspond to the combined rated capacity of all inverters. This is done because kWDC is the unit that most of the PV industry uses. Although costs are reported in kWDC, the total CAPEX includes the cost of the inverter, which has a capacity measured in kWAC.

CAPEX estimates for 2019 reflect continued rapid decline supported by analysis of recent power purchase agreement pricing (Bolinger and Seel 2018) for projects that will become operational in 2019 and beyond.

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, a representative utility-scale PV plant is shown. Although the PV technologies vary, typical plant costs are represented with a single estimate because the CAPEX does not vary with solar resource.

Although the technology market share may shift over time with new developments, the typical plant cost is represented with the projections above.

A system price of $1.10/WDC in 2017 is based on modeled pricing for a 100-MWDC, one-axis tracking systems quoted in Q1 2018 as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018) , adjusted for inflation. The $1.10/WDC price in 2018 is based on modeled pricing for a 100-MWDC, one-axis tracking systems quoted in Q1 2018 as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018) , adjusted for inflation. The 2017 and 2018 bottom-up benchmarks are reflective of an overnight capital cost, which is in line with the ATB methodology of inputting overnight capital cost and calculating construction financing to derive CAPEX. We focus on larger systems for the 2017 and 2018 values to better align with the current trends in utility-scale installations. EIA (2019) reported that 94 PV installations totaling 4.3 GWAC were placed in service in 2018 in the United States. While this represents an average of approximately 46 MWAC, 78% of the installed capacity in 2018 came from systems greater than 50 MWAC, and 38% from systems greater than 100 MWAC. Regardless, both 2017 and 2018 figures are in line with other estimated system prices reported by Feldman and Margolis (2018) .

Future Year Projections

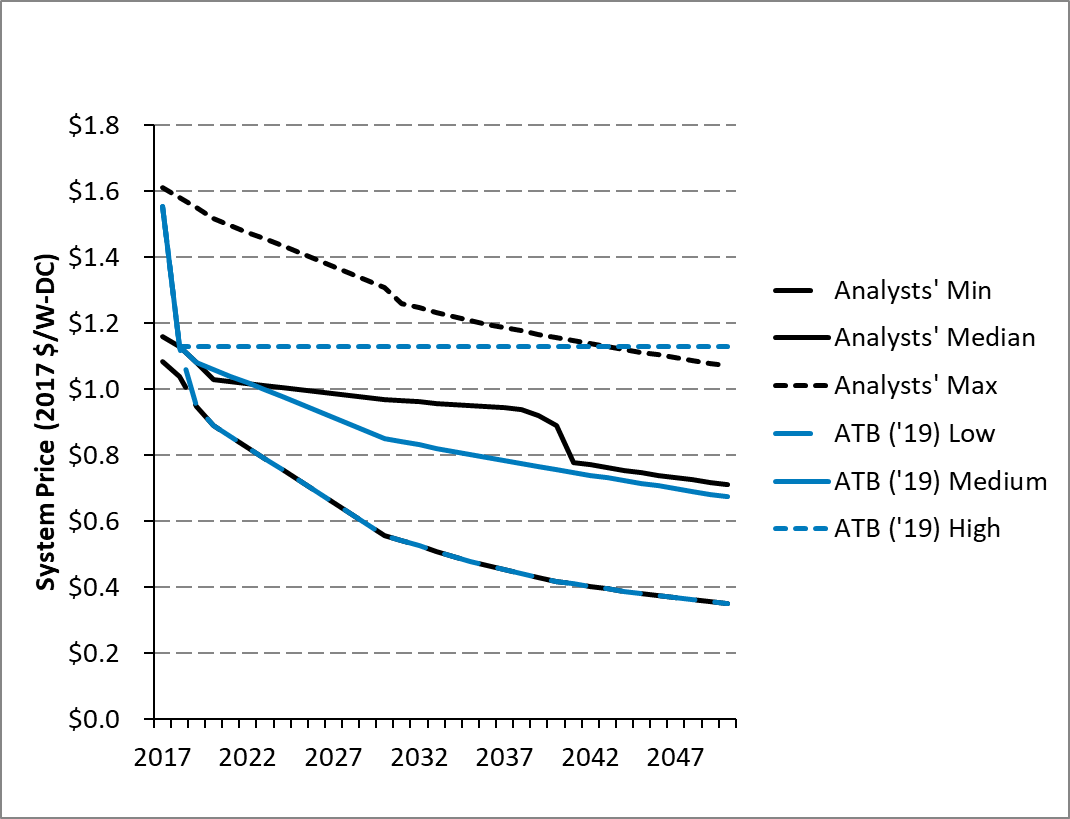

Projections of future utility-scale PV plant CAPEX are based on 11 system price projections from 9 separate institutions. Projections include:

- Short-term projections made in the past two years: (Avista 2017), (BNEF 2018), (E3 2017), (GTM Research 2018), and (IEA 2018)

- Long-term projections made in the last three years: (ABB 2017), (BNEF 2017), (EIA 2019b), (EIA 2018), (IEA 2018c), (IRENA 2016), and (Lam, Branstetter, and Azevedo 2018) .

We adjusted the "min," "median," and "max" projections in a few

different ways. All 2017 and 2018 pricing are based on the bottom-up

benchmark analysis reported in U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System

Cost Benchmark Q1 2018

We adjusted the Mid and Low projections for 2019-2050 to remove distortions caused by the combination of forecasts with different time horizons and based on internal judgment of price trends. Without such adjustments, the Mid and Low projections would have increased over time in certain years, or they would have decreased dramatically due to the end of a projection's timeline. The Constant cost scenario is kept constant at the 2018 CAPEX value and assumes no improvements beyond 2018.

The largest annual reductions in CAPEX for the Low projection occur from 2018 to 2019, dropping 14%, which is on par with the average reduction in reported price of 14% between 2010 and 2017 (Bolinger and Seel 2018) . Initial reported pricing for utility-scale power purchase agreements (PPAs) placed in service in 2018 fell to approximately $42/MWh (Real $2018), which is consistent in price with PPAs executed in 2015 and 2016, representing a two- to three-year lag from execution to installation. Looking forward, the capacity average executed PPA price for a provisional set of U.S. projects in 2018 was approximately $23/MWh (Real $2018). If PPAs executed in 2018 follow a similar two-year lag, we would expect those systems to be installed in 2020-2021; therefore, we could see the capacity-weighted average PPA price for systems installed in the year fall from $42/MWh in 2018 to $23/MWh in 2020, or 46% less. The capacity average executed PPA price in 2017 was 15% lower than the capacity-weighted average PPA price for a system installed in 2017. PPA pricing and CAPEX are not perfectly correlated-annual reductions of PPA and CAPEX only have a correlation coefficient of 0.17 from 2010 to 2017; however, the correlation coefficient for reduction over a four-year period in PPA and CAPEX during that time (i.e., PPA or CAPEX reduction from 2010 to 2014, 2011 to 2015, 2012 to 2016, and 2013 to 2017) was 0.95 – from 2010 to 2017, the capacity-weighted average PPA price and CAPEX for systems installed in that year fell 69% and 61% respectively (Bolinger and Seel 2018) .

Looking to 2030 and beyond, various technical, market, and business improvements could significantly reduce PV system costs further, in line with the low and mid CAPEX projections. Many manufacturers have near-term road maps that will greatly exceed the 18.1% module efficiency assumed in the 2018 utility-scale overnight capital cost benchmark; for example, Canadian Solar reported that its mass produced cells will increase 20%-22% in 2018 (depending on cell line) to 22%-24% by 2021 (Canadian Solar 2019) . However, greater efficiencies can still be achieved if the industry can translate gains in the laboratory to mass production, as the current monocrystalline cell efficiency record in a laboratory is 26.1% (EIA 2016a) and (NREL: "Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart"). Additionally, the industry also has the potential to significantly increase cell efficiencies by using double junction cell technology; for example, perovskite on top of c-Si has a theoretical maximum efficiency of 44% (Fuscher and Bruno 2016) .

Other factors are also expected to significantly decrease PV system

prices. For example, at the end of 2018, the global module price was

approximately $0.22/W

(Feldman and Margolis 2018)

compared to the 2018 utility-scale CAPEX benchmark, which assumes a

module price of $0.47/W

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future CAPEX costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

For the ATB, and based on EIA (2016a) and the NREL Solar PV Cost Model (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018), the utility-scale solar PV plant envelope is defined to include:

- Hardware

- Module supply

- Power electronics, including inverters

- Racking

- Foundation

- AC and DC wiring materials and installation

- Electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting modules to each other and to the control center

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Land acquisition, site preparation, installation of underground utilities, access roads, fencing, and buildings for operations and maintenance

- Project indirect costs, including costs related to engineering, distributable labor and materials, construction management start up and commissioning, and contractor overhead costs, fees, and profit

- Financial Costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Electrical interconnection, including onsite electrical equipment (e.g., switchyard), a nominal-distance spur line (< 1 mile), and necessary upgrades at a transmission substation; distance-based spur line cost (GCC) not included in the ATB

- Interest during construction estimated based on six-month duration accumulated 100% at half-year intervals and an 8% interest rate (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

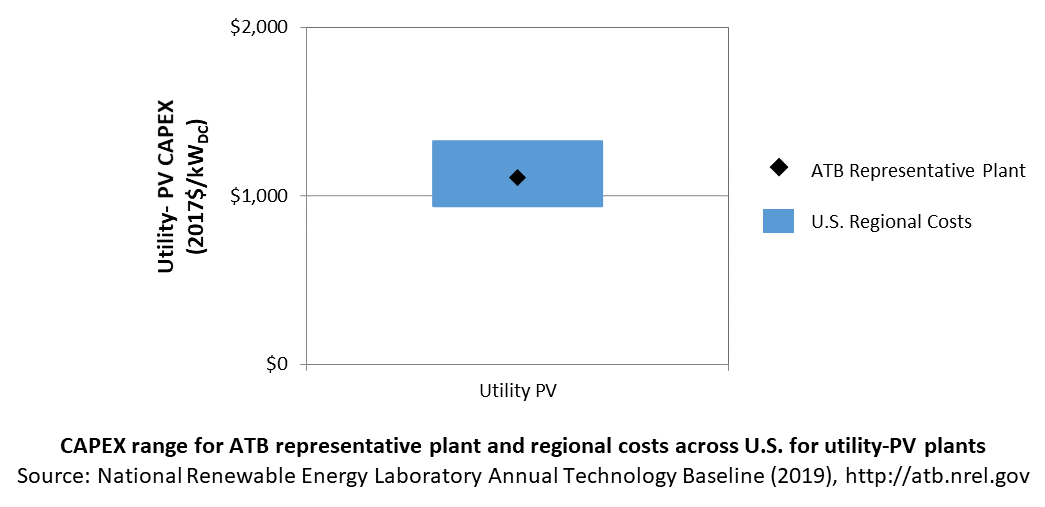

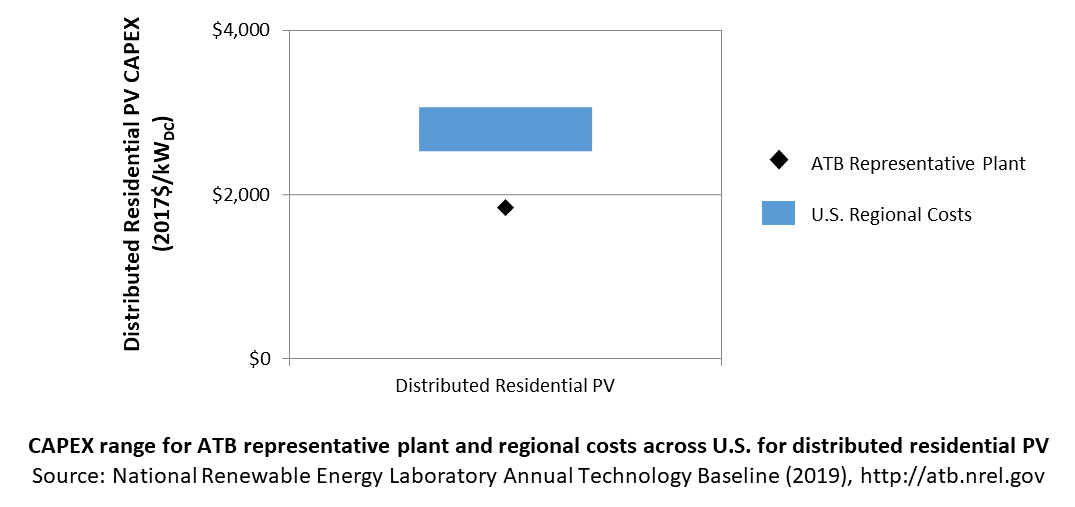

In the ATB, CAPEX represents a typical one-axis utility-scale PV plant and does not vary with resource. The difference in cost between tracking and non-tracking systems has been reduced greatly in the United States. Regional cost effects associated with labor rates, material costs, and other regional effects as defined by EIA (2016b) expand the range of CAPEX. Unique land-based spur line costs based on distance and transmission line costs for potential utility-PV plant locations expand the range of CAPEX even further. The following figure illustrates the ATB representative plant relative to the range of CAPEX including regional costs across the contiguous United States. The ATB representative plants are associated with a regional multiplier of 1.0.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., but the ReEDS model does include 134 regional multipliers (EIA 2016b).

CAPEX in the ATB does not include a geographically determined spur line (GCC) from plant to transmission grid, but the ReEDS model calculates a unique value for each potential PV plant.

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent the annual fixed expenditures required to operate and maintain a solar PV plant over its lifetime, including:

- Insurance, property taxes, site security, legal and administrative fees, and other fixed costs

- Present value and annualized large component replacement costs over technical life (e.g., inverters at 15 years)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of solar PV plants, transformers, etc. over the technical lifetime of the plant (e.g., general maintenance, including cleaning and vegetation removal).

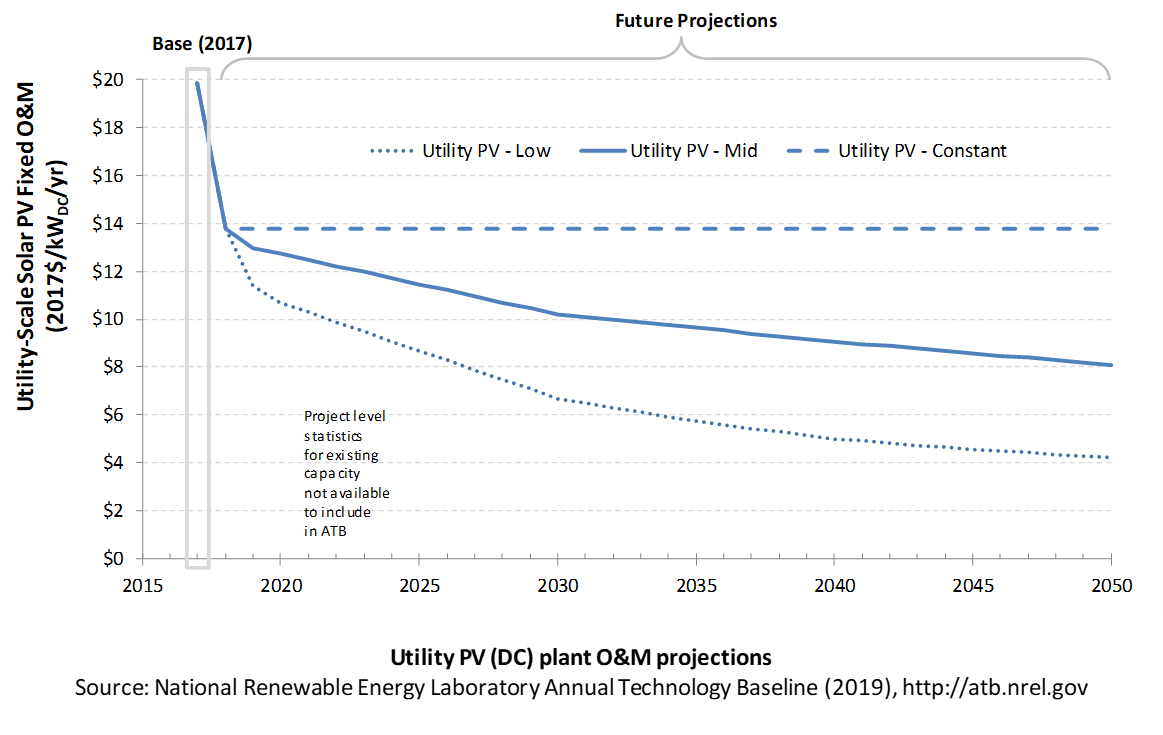

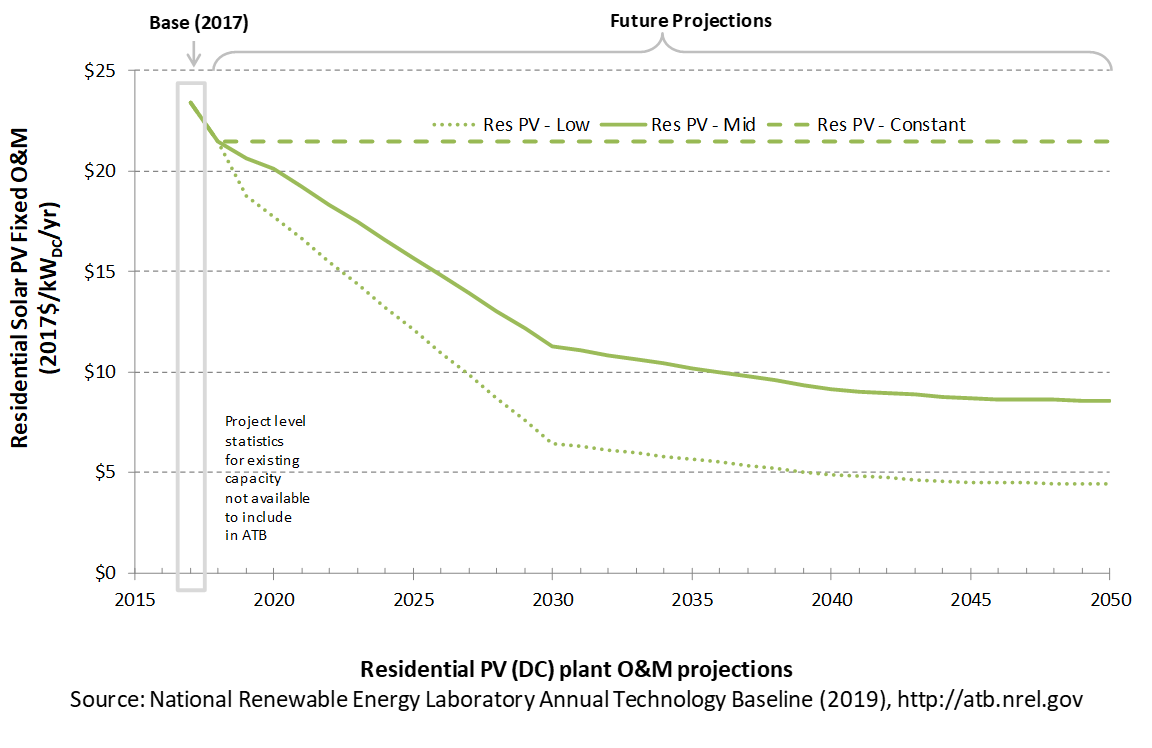

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed O&M (FOM) costs. Three cost scenarios are represented. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

FOM of $20/kWDC - yr is based on modeled pricing for a 100-MWDC, one-axis tracking systems quoted in Q1 2017 as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018), adjusted for inflation. The values in this report (ATB 2019) are higher than those from ATB 2018 because they better align with the benchmarks reported in Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018); the previous edition relied solely on an O&M-to-CAPEX ratio, derived from multiple reports. A wide range in reported prices exists in the market, in part depending on the maintenance practices that exist for a particular system. These cost categories include asset management (including compliance and reporting for incentive payments), different insurance products, site security, cleaning, vegetation removal, and failure of components. Not all these practices are performed for each system; additionally, some factors depend on the quality of the parts and construction. NREL analysts estimate O&M costs can range from $0 to $40/kWDC - yr.

Future Year Projections

FOM for 2018 is also based on pricing reported in Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018), adjusted for inflation. From 2019-2050, FOM is based on the historical average ratio of O&M costs ($/kW-yr) to CAPEX costs ($/kW), 1.2:100, as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018). This ratio is higher than the ratio of O&M costs to historically reported CAPEX costs of 0.7:100, which are derived from 2011 to 2017 historical data reported by Bolinger and Seel (2018), as well as the ratio of O&M costs to CAPEX costs of 1.0:100, which is derived from (IEA 2016) and (Lazard 2018). Historically reported data suggest O&M and CAPEX cost reductions are correlated; from 2011 to 2017, fleetwide average O&M and CAPEX costs fell 50% and 58% respectively, as reported by Bolinger and Seel (2018).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

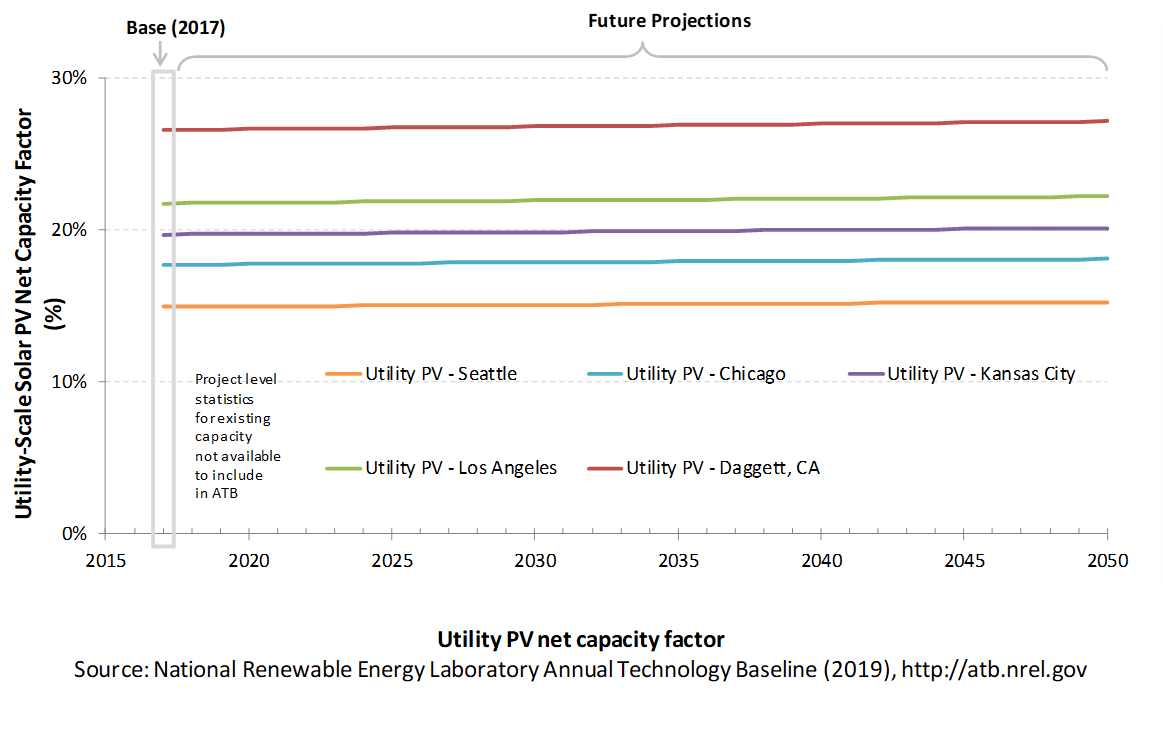

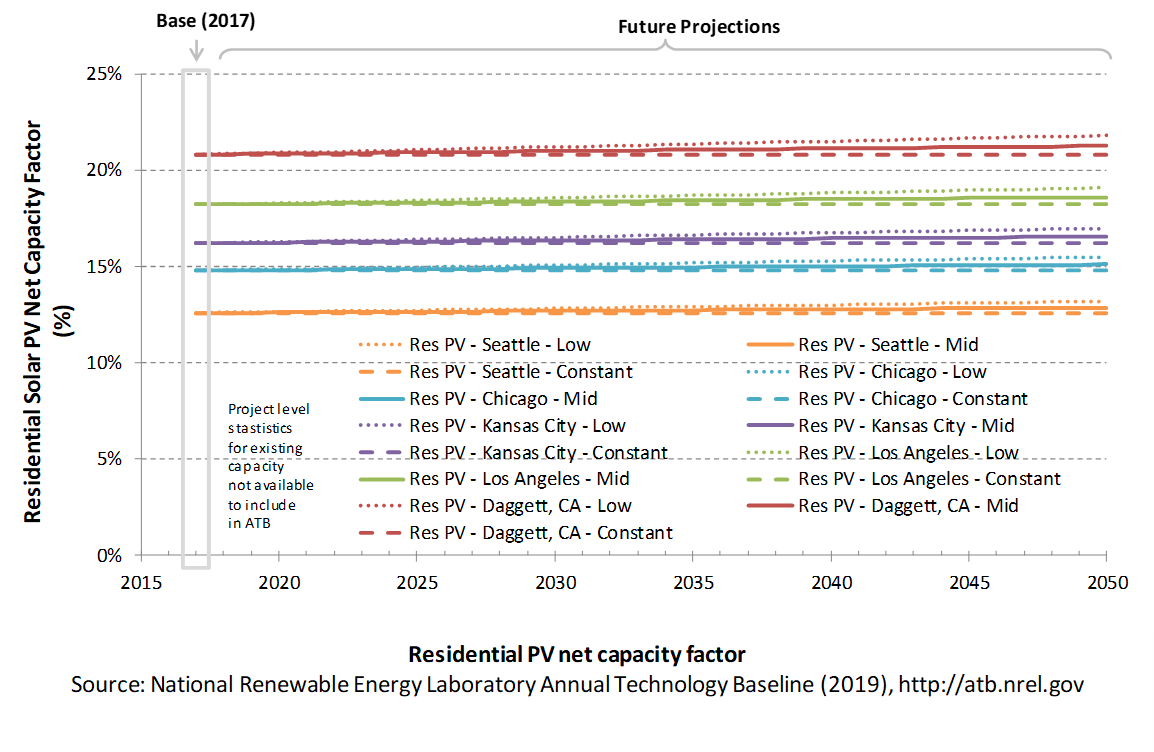

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

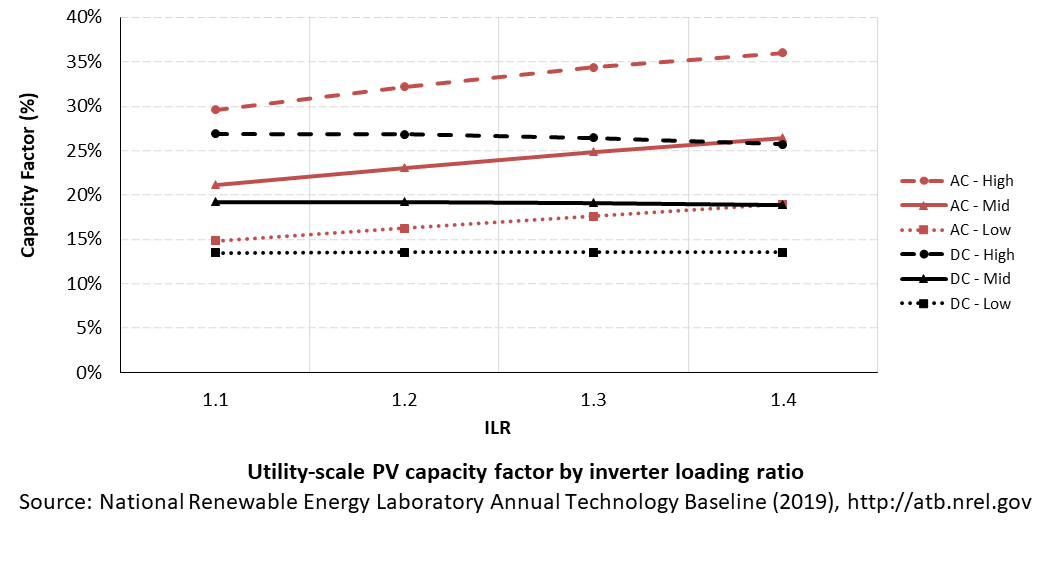

Other technologies' capacity factors are represented in exclusively AC units; however, because PV pricing in this ATB documentation is represented in $/kWDC, PV system capacity is a DC rating. The PV capacity factor is the ratio of annual average energy production (kWhAC) to annual energy production assuming the plant operates at rated DC capacity for every hour of the year. For more information, see Solar PV AC-DC Translation.

The capacity factor is influenced by the hourly solar profile, technology (e.g., thin-film versus crystalline silicon), axis type (e.g., none, one, or two), expected downtime, and inverter losses to transform from DC to AC power. The DC-to-AC ratio is a design choice that influences the capacity factor. PV plant capacity factor incorporates an assumed degradation rate of 0.75%/year (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018)in the annual average calculation. R&D could lower degradation rates of PV plant capacity factor; future projections for Mid and Low cost scenarios reduce degradation rates by 2050, using a straight-line basis, to 0.5%/year and 0.2%/year respectively.

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in solar resource in the contiguous United States. The range of the Base Year estimates illustrate the effect of locating a utility-scale PV plant in places with lower or higher solar irradiance. These five values use specific locations as examples of high (Daggett, California), high-mid (Los Angeles, California), mid (Kansas City, Missouri), low-mid (Chicago, Illinois), and low (Seattle, Washington) resource areas in the United States as implemented in the System Advisor Model using PV system characteristics from Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018).

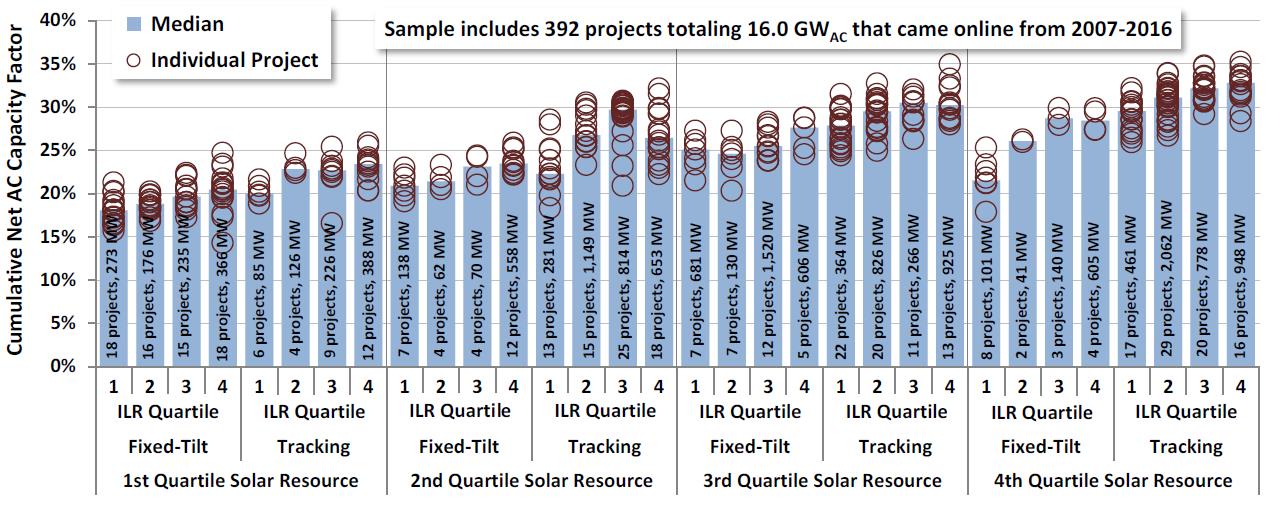

PV system inverters, which convert DC energy/power to AC energy/power, have AC capacity ratings; therefore, the capacity of a PV system is rated in MWAC, or the aggregation of all inverters' rated capacities, or MWDC, or the aggregation of all modules' rated capacities. The capacity factor calculation uses a system's rated capacity, and therefore, capacity factor can be represented using exclusively AC units or using AC units for electricity (the numerator) and DC units for capacity (the denominator). Both capacity factors will result in the same LCOE as long as the other variables use the same capacity rating (e.g., CAPEX in terms of $/kWDC). PV systems' DC ratings are typically higher than their AC ratings; therefore, the capacity factor calculated using a DC capacity rating has a higher denominator. In the ATB, we use capacity factors of 15.9%, 18.9%, 21.0%, 23.2%, and 28.3% for the first year of a PV project and adjust the values to reflect an average capacity factor for the lifetime of a project, calculated with MWDC, assuming 0.75% module capacity degradation per year in the Base Year and declining to 0.5% and 0.2% module capacity degradation per year by 2050 for the Mid and Low cost scenarios. The adjusted average capacity factor values used in the ATB Base Year are 14.9%, 17.7%, 19.7%, 21.7%, and 26.6%. These numbers would change to approximately 19.4%, 23.0%, 25.6%, 29.3%, and 34.5% if the ATB used MWAC. The following figure illustrates capacity factor – both DC and AC – for a range of inverter loading ratios for the Base Year. The ATB capacity factor assumptions are based on ILR = 1.3.

Recent Trends

At the end of 2017, the capacity-weighted average AC capacity factor for all U.S. projects installed at the time was 26.0% (including fixed-tilt systems), but individual project-level capacity factors exhibited a wide range (14.3%-35.2%).

The capacity-weighted average capacity factor was more closely in line with the higher end of the range because 55% of installed capacity from the data set was placed in service in the past two years of when the data were collected (and therefore have not degraded substantially), and 67% of the installed capacity was in the southwestern United States or California, where the average capacity factor was 29.8% for one-axis systems and 25.2% for fixed-tilt systems (Bolinger and Seel 2018).

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, a range of capacity factors associated with the range of latitude in the contiguous United States is shown.

Over time, PV plant output is reduced. This degradation (at 0.75%) is accounted for in ATB estimates of capacity factor. The ATB capacity factor estimates represent estimated annual average energy production over a 30-year lifetime.

These DC capacity factors are for a one-axis tracking system with a DC-to-AC ratio of 1.3.

Future Year Projections

Projections of capacity factors for plants installed in future years are unchanged from the Base Year for the Constant cost scenario. Capacity factors for Mid and Low cost scenarios are projected to increase over time, caused by a straight-line reduction in PV plant capacity degradation rates from 0.75%, reaching 0.5%/year and 0.2%/year by 2050 for the Mid and Low cost scenarios respectively. The following table summarizes the difference in average capacity factor in 2050 caused by different degradation rates in the Constant, Mid, and Low cost scenarios.

| Seattle, WA | Chicago, IL | Kansas City, MO | Los Angeles, CA | Daggett, CA | |

| Low Cost (0.30% degradation rate) | 15.5% | 18.4% | 20.5% | 22.6% | 27.6% |

| Mid Cost (0.50% degradation rate) | 15.2% | 18.1% | 20.1% | 22.2% | 27.1% |

| Constant Cost (0.75% degradation rate) | 14.9% | 17.7% | 19.7% | 21.7% | 26.6% |

Solar PV plants have very little downtime, inverter efficiency is already optimized, and tracking is already assumed. That said, there is potential for future increases in capacity factors through technological improvements beyond lower degradation rates, such as less panel reflectivity and improved performance in low-light conditions.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model output capacity factors for wind and solar PV can be lower than input capacity factors due to endogenously estimated curtailments determined by system operation.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

Currently, CAPEX – not LCOE – is the most common metric for PV cost. Due to differing assumptions in long-term incentives, system location and production characteristics, and cost of capital, LCOE can be confusing and often incomparable between differing estimates. While CAPEX also has many assumptions and interpretations, it involves fewer variables to manage. Therefore, PV projections in the ATB are driven primarily by CAPEX cost improvements, along with minor improvements in operational cost and cost of capital.

The Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases explore the range of possible outcomes of future PV cost improvements:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no improvements made beyond today

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: current expectations of price reductions in a "business-as-usual" scenario

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: expectations of potential cost reductions given improved R&D funding, favorable financing, and more aggressive global deployment targets.

While CAPEX is one of the drivers to lower costs, R&D efforts continue to focus on other areas to lower the cost of energy from utility-scale PV, such as longer system lifetime and improved performance.

Projections of future utility-scale PV plant CAPEX are based on 11 system price projections from 9 separate institutions. The short-term forecasts were primarily provided by market analysis firms with expertise in the PV industry, through a subscription service with NREL. The long-term forecasts primarily represent the collection of publicly available, unique forecasts with either a long-term perspective of solar trends or through capacity expansion models with assumed learning by doing. Short-term U.S. price forecasts made in the past two years include: (Avista 2017), (BNEF 2018), (E3 2017), (GTM Research 2018), and (IEA 2018b). Long-term projections made in the past three years include (ABB 2017), (BNEF 2017), (EIA 2019b), (IEA 2018a), (IRENA 2016), and (Lam, Branstetter, and Azevedo 2018).

- Short-Term Forecast Institutions: Avista, Bloomberg New Energy Finance, CAISO, GTM Research, International Energy Agency

- Long-Term Forecast Institutions: ABB; Bloomberg New Energy Finance; International Energy Agency; IRENA; Lam, Branstetter, and Azevedo (2018); U.S. Energy Information Administration.

To adjust all projections to the ATB's assumption of single-axis tracking systems, 7% was added to all price projections that assumed fixed-tilt tracking technology, and 3.5% was added for all price projections that did not list whether the technology was fixed-tilt or single-axis tracking. All price projections quoted in $/WAC were converted to $/WDC using a 1.3 ILR. In instances in which literature projections did not include all years, a straight-line change in price was assumed between any two projected values. To generate Mid and Low technology cost scenarios, we took the "median" and "min" of the data sets; however, we only included short-term U.S. forecasts until 2030 as they focus on near-term pricing trends within the industry. Starting in 2030, we include long-term global and U.S. forecasts in the data set, as they focus more on long-term trends within the industry. It is also assumed that after 2025, U.S. prices will be on par with global averages; the federal tax credit for solar assets reverts down to 10% for all projects placed in service after 2023, which has the potential to lower upfront financing costs and remove any distortions in reported pricing, compared to other global markets. Additionally, a larger portion of the United States will have a more mature PV market, which should result in a narrower price range. Changes in price for the Mid and Low technology cost scenarios between 2020 and 2030 are interpolated on a straight-line basis.

We adjusted the "median" and "min" projections in a few different ways. All 2017 and 2018 pricing are based on the bottom-up benchmark analysis reported in U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System Cost Benchmark Q1 2018 (adjusted for inflation)(Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018). These figures are in line with other estimated system prices reported in Q2/Q3 2018 Solar Industry Update (Feldman and Margolis 2018).

We adjusted the Mid and Low projections for 2019-2050 to remove distortions caused by the combination of forecasts with different time horizons and based on internal judgment of price trends. The Constant technology cost scenario is kept constant at the 2018 CAPEX value, assuming no improvements beyond 2018.

We derive future FOM based on the historical average ratio of O&M costs ($/kW-yr) to CAPEX costs ($/kW), 1.2:100, as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018). Historically reported data suggest O&M and CAPEX cost reductions are correlated; from 2011 to 2017 fleetwide average O&M and CAPEX costs fell 50% and 58% respectively, as reported by Bolinger and Seel (2018).

O&M cost reductions are likely to be achieved over the next decade by a transition from manual and reactive O&M to semi-automated and fully automated O&M where possible. While many of these tasks are very site and region specific, emerging technologies have the potential to reduce the total O&M costs across all systems. For example, automated processes of sensors, monitors, remote-controlled resets, and drones to perform operations have the potential to allow O&M on PV systems to operate more efficiently at lower cost. Not all tasks have a clear path of automation due to complexity, safety, and some policy. This is one reason some level of manual interventions will likely exist for quite some time. Also, as systems age, O&M tasks that rely strictly on manpower are likely to increase in cost over the system lifetime.

Projections of capacity factors for plants installed in future years are unchanged from 2018 for the Constant cost scenario. Capacity factors for Mid and Low cost scenarios are projected to increase over time, caused by a straight-line reduction in PV plant capacity degradation rates, reaching 0.5%/year and 0.2%/year by 2050 for the Mid and Low cost scenarios respectively.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

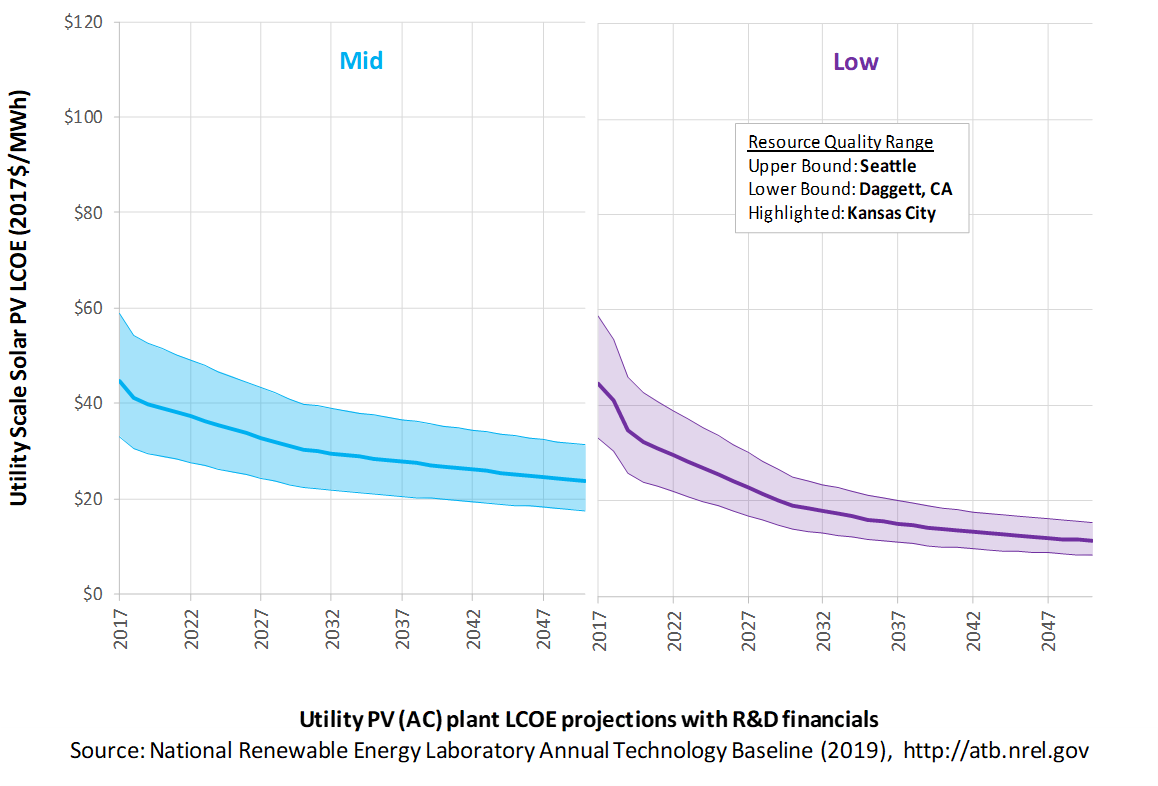

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a summary metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

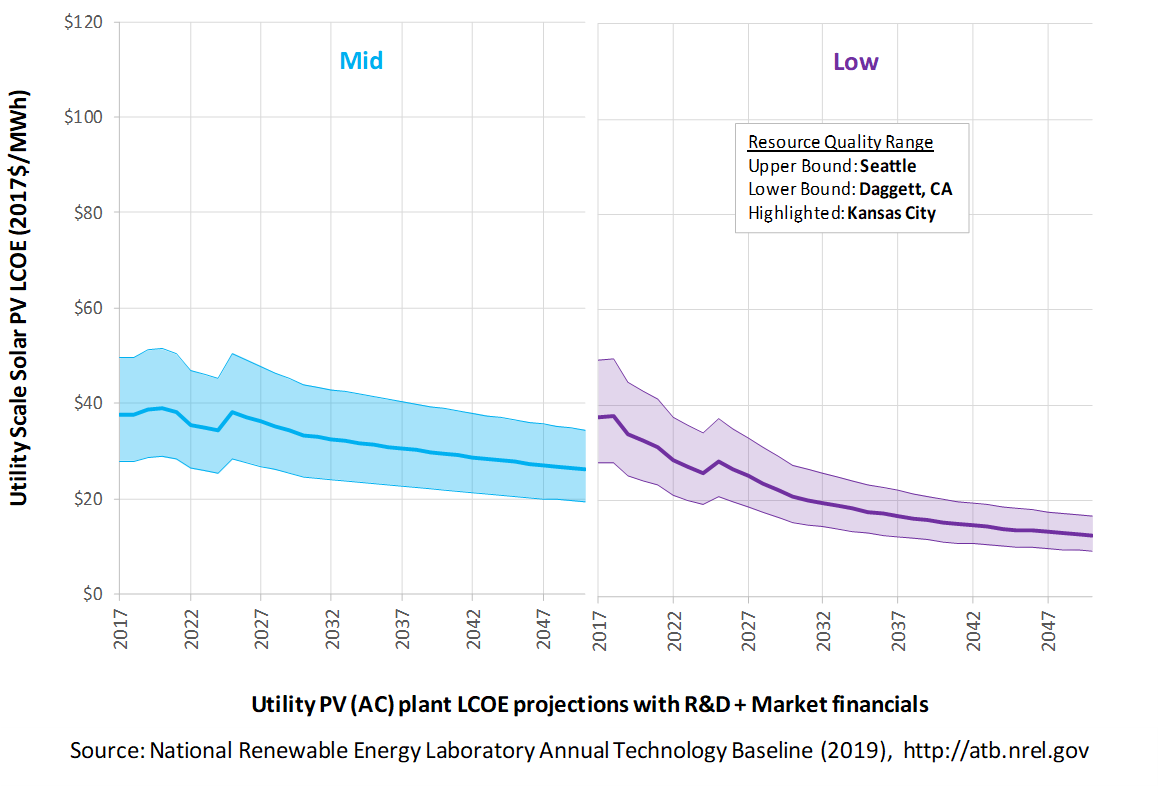

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for utility-scale PV across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs but not in the upfront capital costs (e.g., developer fees and contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside of the United States, due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g., offshore wind in Europe) or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform and tax credits. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term utility-scale PV plants are associated with Utility PV: Kansas City. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures. In the R&D + Market LCOE case, there is an increase in LCOE from 2018-2020, caused by an increase WACC, and an increase from 2023-2024, caused by the reduction in tax credits.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA 2019b)and excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2019 as well as effects of tax reform, and tax credits. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE.

A constant cost recovery period – over which the initial capital investment is recovered – of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below.

- Modules

- Increased module efficiencies and increased production-line throughput to decrease CAPEX; overhead costs on a per-kilowatt basis will go down if efficiency and throughput improvement are realized

- Reduced wafer thickness or the thickness of thin-film semiconductor layers

- Development of new semiconductor materials

- Development of larger manufacturing facilities in low-cost regions

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Increased module efficiency, reducing the size of the installation

- Development of racking systems that enhance energy production or require less robust engineering

- Integration of racking or mounting components in modules

- Reduction of supply chain complexity and cost

- Creation of standard packaged system design

- Improvement of supply chains for BOS components in modules

- Improved power electronics

- Improvement of inverter prices and performance, possibly by integrating microinverters

- Decreased installation costs and margins

- Reduction of supply chain margins (e.g., profit and overhead charged by suppliers, manufacturer, distributors, and retailers); this will likely occur naturally as the U.S. PV industry grows and matures

- Streamlining of installation practices through improved workforce development and training and developing standardized PV hardware

- Expansion of access to a range of innovative financing approaches and business models

- Development of best practices for permitting interconnection and PV installation such as subdivision regulations, new construction guidelines, and design requirements.

FOM cost reduction represents optimized O&M strategies, reduced component replacement costs, and lower frequency of component replacement.

Residential PV Systems

Representative Technology

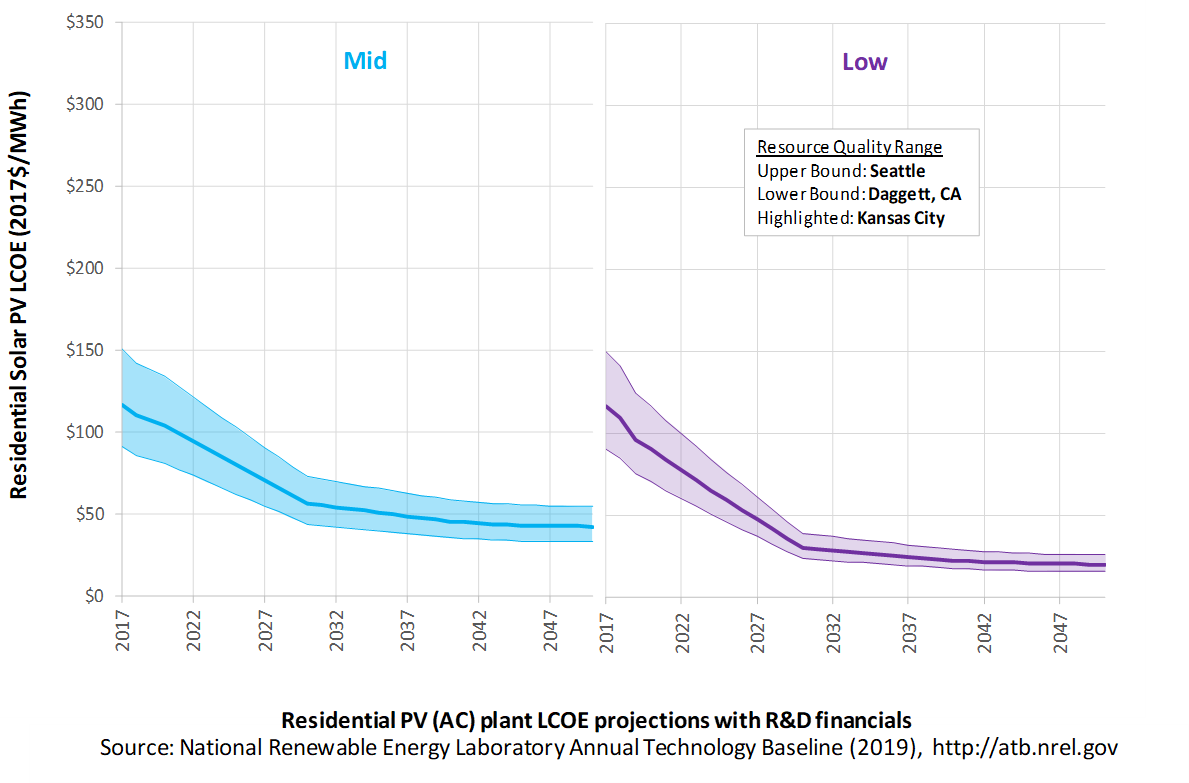

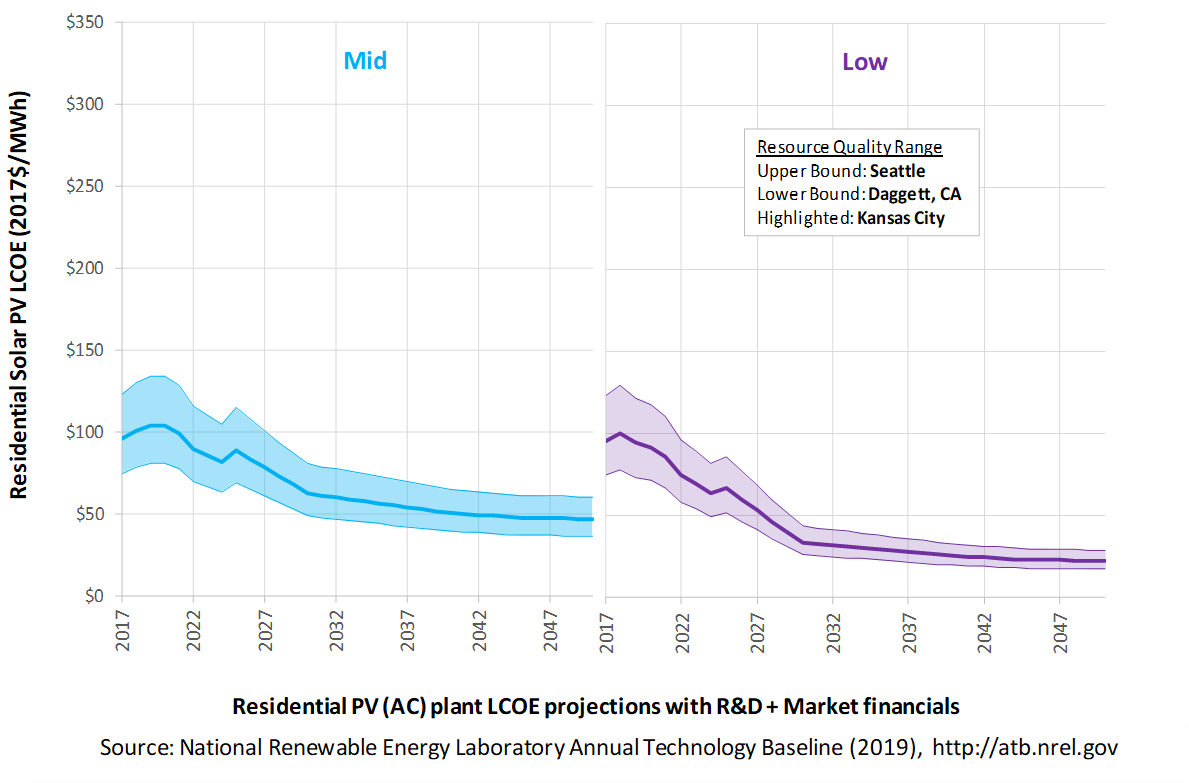

For the ATB, residential PV systems are modeled for a 5.0-kWDC fixed tilt (25°), roof-mounted system. Flat-plate PV can take advantage of direct and indirect insolation, so PV modules need not directly face and track incident radiation. This gives PV systems a broad geographical application, especially for residential PV systems.

Resource Potential