Offshore Wind

Representative Technology

In 2016, the first offshore wind plant (30 MW) commenced commercial operation in the United States near Block Island (Rhode Island). In 2018, Vineyard Wind LLC and Massachusetts electric distribution companies submitted a 20-year power purchase agreement (PPA) for 800 MW of offshore wind generation and renewable energy certificates to the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities for review and approval. In the ATB, cost and performance estimates are made for commercial-scale projects with 600 MW in capacity. The ATB Base Year offshore wind plant technology reflects a machine rating of 6 MW with a rotor diameter of 155 m and hub height of 100 m, which is typical of European projects installed in 2016 and 2017 and the turbine rating installed at the Block Island Wind Farm (GE Haliade 150-6MW).

Resource Potential

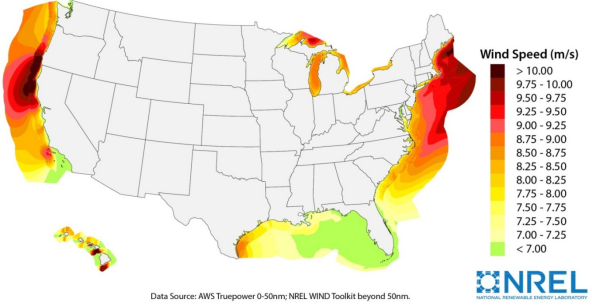

Wind resource is prevalent throughout major U.S. coastal areas, including the Great Lakes. The resource potential exceeds 2,000 GW, excluding Alaska, based on domain boundaries from 50 nautical miles (nm) to 200 nm, turbine hub heights of 100 m (previously 90 m), and a capacity array power density of 3 MW/km2(Walt Musial et al. 2016). A range of technology exclusions were applied based on maximum water depth for deployment, minimum wind speed, and limits to floating technology in freshwater surface ice. Resource potential was represented by more than 7,000 areas for offshore wind plant deployment after accounting for competing use and environmental exclusions, such as marine protected areas, shipping lanes, pipelines, and others.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

Based on a resource assessment (Walt Musial et al. 2016), LCOE was estimated at more than 7,000 areas (with a total capacity of approximately 2,000 GW). Using an updated version of NREL's Offshore Regional Cost Analyzer (ORCA) (Beiter et al. 2016), a variety of spatial parameters were considered, such as wind speeds, water depth, distance from shore, distance to ports, and wave height. CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor are calculated for each geographic location using engineering models, hourly wind resource profiles, and representative sea states. ORCA was calibrated to the latest cost and technology trends observed in the U.S. and European offshore wind markets, including:

- Turbine CAPEX: $1,300/kW were assumed for the Base Year to account for decreases in Turbine CAPEX that were observed in global offshore wind markets.

- Turbine Rating: A turbine technology trend of 6 MW (Base Year), 8 MW (2022 commercial operation date [COD]), 10 MW (2027 COD), and 10 MW (2032 COD) was assumed to correspond to recent technology trends. While higher turbine ratings may be commercially available during this period (e.g., up to 15-MW turbine ratings are expected to be commercially available by the early 2030s), the selected turbine ratings are intended to reflect the average turbine rating of the operating U.S. offshore wind fleet.

- Export System Cable Costs: A reduction of 25% in comparison to an earlier version of ORCA (Beiter et al. 2016) was assumed for the Base Year to account for increased competition within the supply chain in recent years and for changes in material use and commodity prices.

- Cost Reduction Trajectory: Recent literature was surveyed to identify the most up-to-date cost reduction trends expected for U.S. and European offshore wind projects; the version of ORCA used to estimate cost reduction trajectories are derived from Valpy et al. (2017)(fixed bottom) and Hundleby et al. (2017)(floating).

- Contingency Levels: A markup of 25% above of European contingency levels was assumed to account for the higher risk of installing and operating early offshore wind farms in the United States.

- Lease Area Price: This cost to projects was included to account for the recent increase in the tendered U.S. lease area prices.

The spatial LCOE assessment served as the basis for estimating the ATB baseline LCOE in the Base Year 2017, weighted by the available capacity, for fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind technology. Only sites that exceed a distance to cable landfall of 20 kilometers (km) and a water depth of 10 meters (m) were included in the spatial assessment for the ATB to represent those sites only that are likely to be developed in the near-to-medium term. Long-term average hourly wind profiles are assumed and estimated LCOE reflects the least-cost choice among four substructure types (Beiter et al. 2016):

- Monopile (fixed-bottom)

- Jacket (fixed-bottom)

- Semi-submersible (floating)

- Spar (floating).

The representative offshore wind plant size is assumed to be 600 MW (Beiter et al. 2016). For illustration in the ATB, the full resource potential, represented by 7,000 areas, was divided into 15 techno-resource groups (TRGs), of which TRGs 1-5 are representative of fixed-bottom wind technology and TRGs 6-15 are representative of floating offshore wind technology. The capacity-weighted average CAPEX, O&M, grid connection costs, and capacity factor for each group are presented in the ATB.

For illustration in the ATB, all potential offshore wind plant areas were represented in 15 TRGs with TRGs 1-5 representing fixed-bottom offshore technology and TRGs 6-15 representing floating offshore wind technology. These were defined by resource potential (GW) and have higher resolution on the least-cost TRGs, as these are the most likely sites to be deployed, based on their economics. The following table summarizes the capacity-weighted average water depth, distance to cable landfall, and cost and performance parameters for each TRG. The table includes the relative resource potential. Typical offshore wind installations in 2017 that have spatial and economic conditions that may lend themselves well to near-term deployment are associated with TRG 3.

TRG Definitions for Offshore Wind

| TRG | Weighted Water Depth (m) | Weighted Distance Site to Cable Landfall (km) | Weighted Average CAPEX ($/kW) | Weighted Average OPEX ($/kW/yr) | Weighted Average Net CF (%) | Potential Wind Plant Capacity of Fixed-Bottom/Floating Total (%) | |

| Fixed-Bottom | TRG 1 | 18 | 27 | 3,361 | 105 | 45 | 2 |

| TRG 2 | 22 | 29 | 3,475 | 106 | 44 | 3 | |

| TRG 3 | 24 | 33 | 3,660 | 109 | 44 | 7 | |

| TRG 4 | 29 | 57 | 4,001 | 112 | 41 | 44 | |

| TRG 5 | 31 | 65 | 4,633 | 107 | 30 | 44 | |

| Floating | TRG 6 | 144 | 38 | 4,602 | 77 | 52 | 1 |

| TRG 7 | 159 | 45 | 4,661 | 78 | 51 | 2 | |

| TRG 8 | 157 | 46 | 4,710 | 78 | 49 | 4 | |

| TRG 9 | 148 | 64 | 4,936 | 84 | 49 | 8 | |

| TRG 10 | 107 | 101 | 5,209 | 91 | 47 | 15 | |

| TRG 11 | 375 | 116 | 5,320 | 98 | 43 | 15 | |

| TRG 12 | 467 | 116 | 5,331 | 97 | 36 | 15 | |

| TRG 13 | 663 | 166 | 5,785 | 92 | 34 | 15 | |

| TRG 14 | 432 | 147 | 6,145 | 87 | 30 | 15 | |

| TRG 15 | 468 | 133 | 6,599 | 83 | 28 | 11 | |

Future year projections for CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor in the "Mid Technology Cost" Scenario are derived from the estimated cost reduction potential for offshore wind technologies based on assessments by BVG Associates ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) for 2017-2032. Based on the modeled data between 2017-2032, an (exponential) trend fit is derived for CAPEX, O&M in the "Mid Technology Cost" Scenario, and capacity factor to extrapolate ATB data for years 2033-2050. The specific scenarios are:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB.

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE percentage reduction estimated from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) from the Base Year, which is intended to correspond to a 50% probability of exceedance.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE deviation from the Mid Technology Cost Scenario in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050 informed by analysts' bottom-up technology and cost modeling. This scenario is intended to correspond to a 10%-30% probability of exceedance.

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

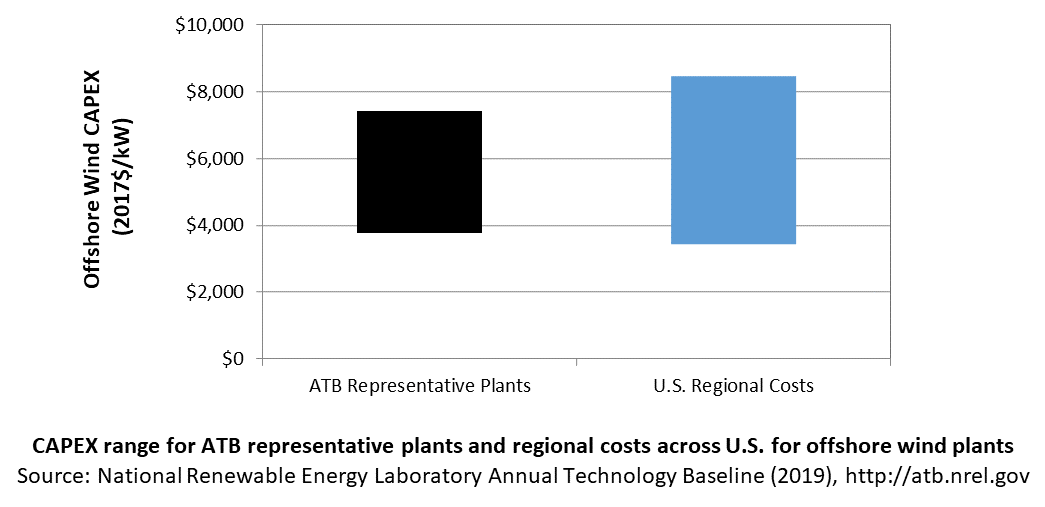

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the wind turbine, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with spatial site parameters in the contiguous United States.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

Based on Moné at al. (2015) and Beiter et al. (2016), the System Cost Breakdown Structure of the ATB for the wind plant envelope is defined to include:

- Wind turbine supply

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Turbine installation, substructure supply and installation

- Site preparation, port and staging area support for delivery, storage, handling, and installation of underground utilities

- Electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting turbines to each other (array cable system costs) and to the cable landfall (export cable system costs)

- Development and project management

- Financial costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Interest during construction estimated based on three-year duration accumulated 40%/40%/20% at half-year intervals and an 8% interest rate (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor). Because transmission infrastructure between an offshore wind plant and the point at which a grid connection is made onshore is a significant component of the offshore wind plant cost, an offshore spur line cost (OffSpurCost) for each TRG is included in the CAPEX estimate. The offshore spur line cost reflects a capacity-weighted average of all potential wind plant areas within a TRG, similar to OCC.

In the ATB, CAPEX represents the capacity-weighted average values of all potential wind plant areas within a TRG and varies with water depth and distance from shore. Regional cost effects associated with labor rates, material costs, and other regional effects as defined by DOE and NREL (2015) expand the range of CAPEX. Unique land-based spur line costs for each of the 7,000 areas based on distance and transmission line costs expand the range of CAPEX even further. The following figure illustrates the ATB representative plants relative to the range of CAPEX including regional costs across the contiguous United States. The ATB representative plants are associated with a regional multiplier of 1.0.

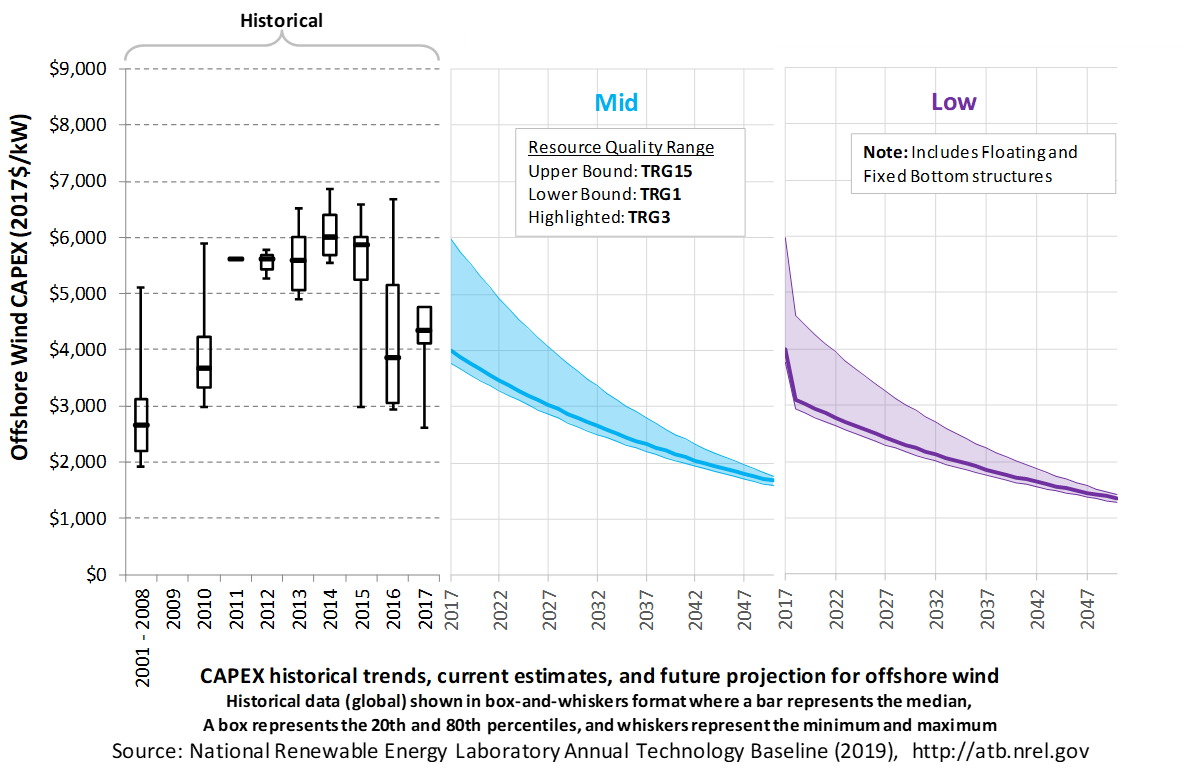

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs. Mid and Low technology cost scenarios are shown. Historical data from offshore wind plants installed globally are shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Recent Trends

Actual global offshore wind plant CAPEX is shown in box-and-whiskers format for comparison to the ATB current CAPEX estimates and future projections. CAPEX estimates for 2017 correspond well with market data for plants installed in 2017. Projections reflect a continuation of the downward trend observed in the recent past and are anticipated to continue based on preliminary data for 2017 projects.

Base Year Estimates

Base Year estimates for CAPEX were derived using an updated version of NREL's Offshore Regional Cost Analyzer (ORCA) (Beiter et al. 2016). A variety of spatial parameters were considered, such as water depth, distance from shore, distance to ports, and wave height to estimate CAPEX. CAPEX estimates were calibrated to correspond to the latest cost and technology trends observed in the U.S. and European offshore wind markets, including:

- Turbine CAPEX: $1,300/kW were assumed for the Base Year to account for decreases in Turbine CAPEX that were observed in global offshore wind markets.

- Turbine Rating: A turbine technology trend of 6 MW (Base Year), 8 MW (2022 commercial operation date [COD]), 10 MW (2027 COD), and 10 MW (2032 COD) was assumed to correspond to recent technology trends. While higher turbine ratings may be commercially available during this period (e.g., up to 15-MW turbine ratings are expected to be commercially available by the early 2030s), the selected turbine ratings are intended to reflect the average turbine rating of the operating U.S. offshore wind fleet.

- Export System Cable Costs: A reduction of 25% in comparison to an earlier version of ORCA (Beiter et al. 2016) was assumed for the Base Year to account for increased competition within the supply chain in recent years and for changes in material use and commodity prices.

- Cost Reduction Trajectory: Recent literature was surveyed to identify the most up-to-date cost reduction trends expected for U.S. and European offshore wind projects; the version of ORCA used to estimate cost reduction trajectories are derived from Valpy et al. (2017)(fixed bottom) and Hundleby et al. (2017) (floating).

- Contingency Levels: A markup of 25% on top of European contingency levels was assumed to account for the higher risk of installing and operating early offshore wind farms in the United States.

- Lease Area Price: This cost to projects was included to account for the recent increase in the tendered U.S. lease area prices.

Future Year Projections

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX percentage reduction estimated from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017) for fixed-bottom and (Hundleby et al. 2017)) from the Base Year, which is intended to correspond to a 50% probability of exceedance.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: CAPEX deviation from the Mid Technology Cost Scenario in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050 informed by analysts' bottom-up technology and cost modeling. This scenario is intended to correspond to a 10%-30% probability of exceedance.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., but the ReEDS model does include 134 regional multipliers (EIA 2013).

The ReEDS model determines offshore spur line and land-based spur line (GCC) uniquely for each of the 7,000 areas based on distance and transmission line cost.

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent the annual fixed expenditures required to operate and maintain a wind plant over its lifetime, including:

- Insurance, taxes, land lease payments and other fixed costs (e.g., project management and administration, weather forecasting, and condition monitoring)

- Present value and annualized large component replacement costs over technical life (e.g., blades, gearboxes, and generators)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of wind plant components, including turbines and transformers, over the technical lifetime of the plant.

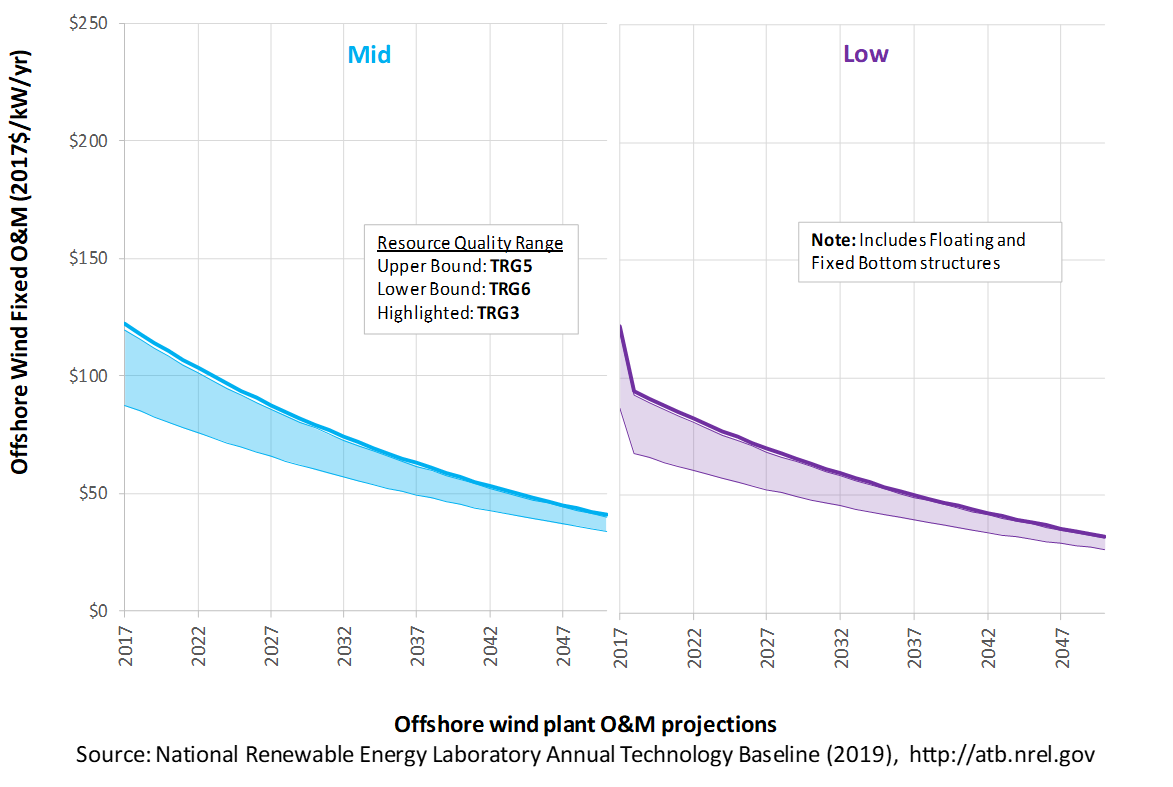

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed and floating O&M (FOM) costs. Mid and Low technology cost scenarios are shown. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year. The range of Base Year O&M estimates reflect the variation in spatial parameters such as distance from shore and metocean conditions.

Base Year Estimates

FOM costs vary by distance from shore and metocean conditions. As a result, O&M costs in the "Mid Technology Cost Scenario" vary from $87/kW-year (TRG 6) to $127/kW-year (TRG 4) in 2017. The average in the ATB "Mid Technology Cost Scenario" for fixed-bottom offshore technology (TRGs 1-5) is $121/kW-year; the corresponding value for floating offshore wind technology (TRGs 6-15) is $97/kW-year.

Future Year Projections

Future fixed-bottom offshore wind technology O&M is estimated to decline 66% by 2050 in the Mid cost case.

Future floating offshore wind technology O&M is estimated to decline 61% by 2050 in the Mid cost case.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

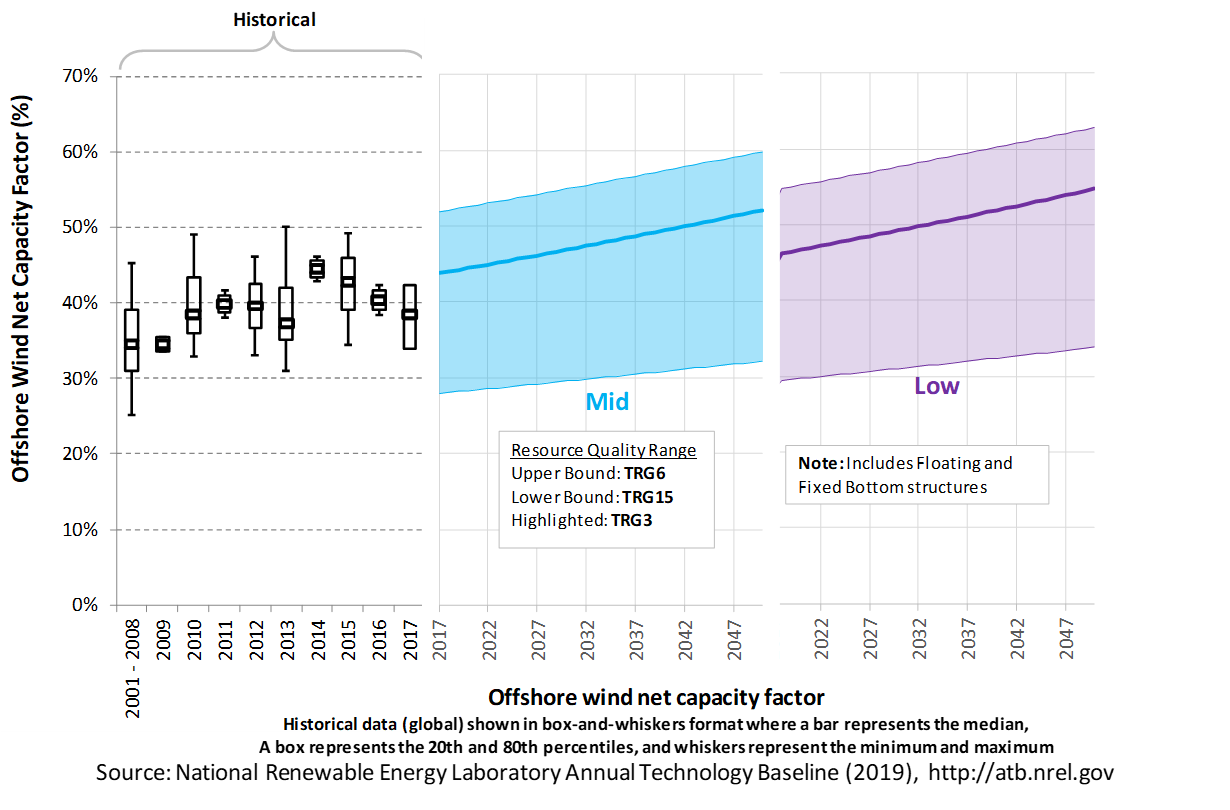

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

The capacity factor is influenced by the rotor swept area/generator capacity, hub height, hourly wind profile, expected downtime, and energy losses within the wind plant. It is referenced to 100-m above-water-surface, long-term average hourly wind resource data from Musial et al. (2016).

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in the wind resource for offshore wind plants in the contiguous United States. Preconstruction estimates for offshore wind plants operating globally in 2015, according to the year in which plants were installed, is shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The range of Base Year estimates illustrates the effect of locating an offshore wind plant in a variety of wind resource (TRGs 1-5 are fixed-bottom offshore wind plants and TRGs 6-15 are floating offshore wind plants). Future projections are shown for Mid and Low technology cost scenarios.

Recent Trends

Preconstruction annual energy estimates from publicly available global operating wind capacity in 2017 (Walter Musial et al. forthcoming) are shown in a box-and-whiskers format for comparison with the ATB current estimates and future projections. The historical data illustrate preconstruction estimated capacity factors for projects by year of commercial online date. The figure shows the comparison between the range of capacity factors defined by the ATB TRGs and the reported capacity factors for projects installed in 2017.

Base Year Estimates

The capacity factor is determined using a representative power curve for a generic NREL-modeled 6-MW offshore wind turbine (Beiter et al. 2016) and includes geospatial estimates of gross capacity factors for the entire resource area (Walt Musial et al. 2016). The net capacity factor considers spatial variation in wake losses, electrical losses, turbine availability, and other system losses. For illustration in the ATB, all 7,000 wind plant areas are represented in 15 TRGs.

Future Year Projections

Projections of capacity factors for plants installed in future years were determined based on estimates obtained from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) for both fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind technologies. Projections for capacity factors implicitly reflect technology innovations such as larger rotors and taller towers that will increase energy capture at the same geographic location without explicitly specifying tower height and rotor diameter changes.

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model output capacity factors for offshore wind can be lower than input capacity factors due to endogenously estimated curtailments determined by scenario constraints.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

ATB projections between the Base Year and 2032 (COD) were derived from an expert elicitation conducted by BVG Associates ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)). The expert elicitation assesses the impact of more than 50 technology innovations on various cost components of European offshore wind farms up to 2032 (COD). The cost impact from technology innovations was assessed by soliciting industry experts about the maximum cost impact from a technology innovation in combination with an assessment of an innovation's commercial readiness and market share in a given year.

For the ATB, three different technology cost scenarios were adapted from the expert survey results for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2015 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB.

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE percentage reduction estimated from BVG ((Valpy et al. 2017), (Hundleby et al. 2017)) from the Base Year, intended to correspond to a 50% probability of exceedance.

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: LCOE deviation from the Mid Technology Cost Scenario in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050 informed by analysts' bottom-up technology and cost modeling. This scenario is intended to correspond to a 10%-30% probability of exceedance.

Expert survey estimates from BVG Associates were normalized to the ATB Base Year starting point and applied to overnight capital costs (OCC), FOM, and annual energy production in 2022 (COD), 2027 (COD), and 2032 (COD). These serve as the ATB Mid projection between 2017-2032 (COD). The ATB Mid scenario is intended to represent a cluster of technology innovations that change the manufacturing, installation, operation, and performance of a wind farm consistent with historical cost reduction rates. The ATB Low scenario is intended to represent a cluster of technology innovations that fundamentally change the manufacturing, installation, operation and performance of a wind farm resulting in considerably higher cost reductions than the ATB Mid scenario. The ATB Low scenario is represented by cost reductions that are twice the rate achieved in the ATB Mid scenario. The percentage reduction in LCOE was applied equally across all TRGs. The cost reductions for ATB Mid and ATB Low scenarios between 2032 and 2050 were extrapolated (i.e., exponentially fit) based on the estimated trend between 2017 and 2032 (COD).

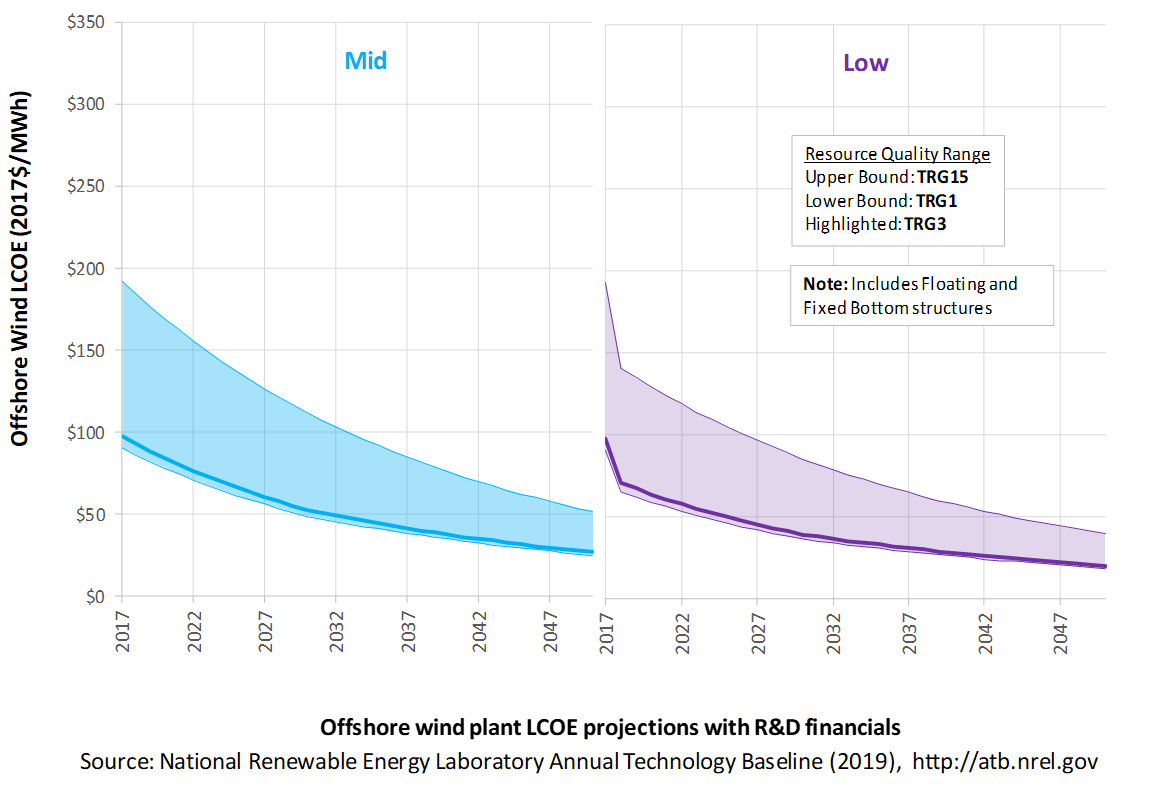

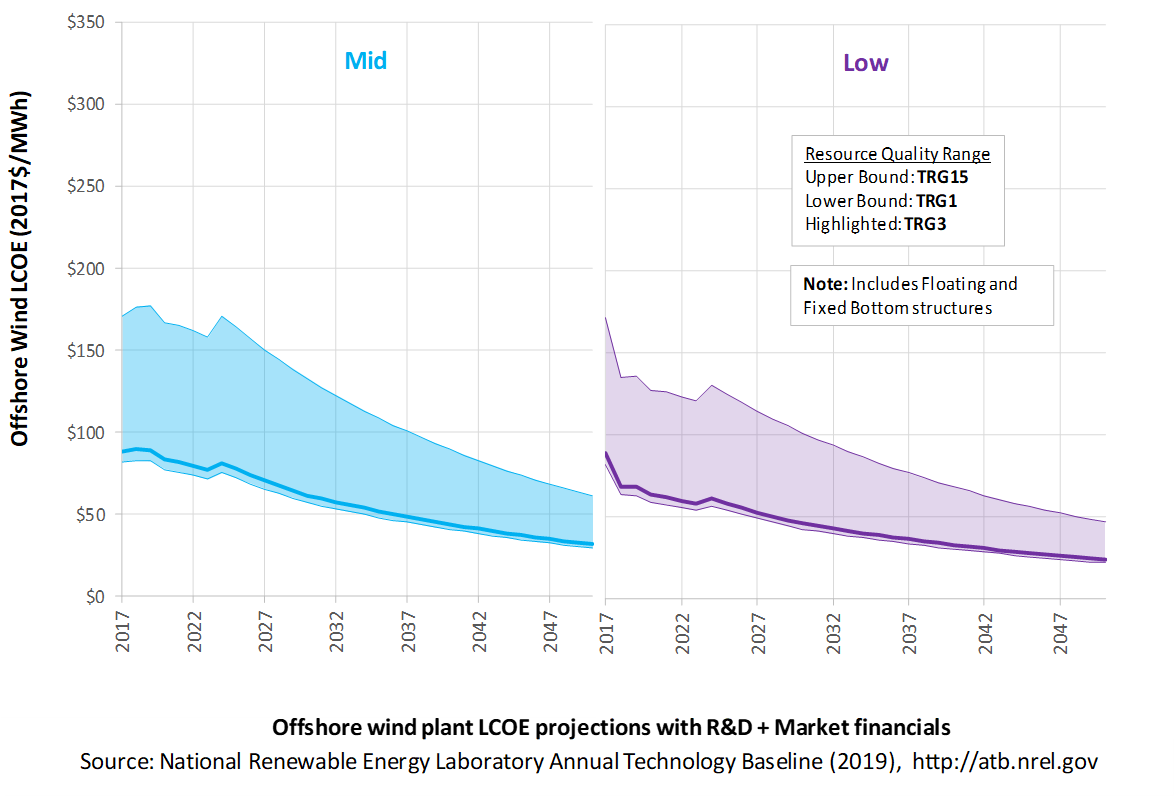

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a summary metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for offshore wind across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform and tax credits. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term offshore wind plants are associated with TRG 3. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA 2019) and excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2019 (EIA 2019) as well as effects of tax reform and tax credits. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE.

A constant cost recovery period-over which the initial capital investment is recovered-of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below:

- The financing conditions assumed for the ATB are applicable to commercial-scale offshore wind projects only. Commercial-scale fixed-bottom offshore wind projects are expected to be installed starting in the early 2020s (Walter Musial et al. forthcoming). Offshore wind projects using floating technology are in a pre-commercial phase currently (i.e., multi-turbine arrays between 12-50 MW in size) for which the ATB financial assumptions are likely too favorable. Once floating technology is deployed at commercial scale, the ATB financial assumptions are expected to appropriately reflect the terms of financing. The use of floating technology for commercial-scale projects is expected by the mid-2020s. Continued turbine scaling to larger-megawatt turbines with larger rotors such that swept area/megawatt capacity decreases resulting in higher capacity factors for a given location

- Greater market competition in the production of primary components (e.g., turbines, support structure), and installation services

- Economy-of-scale and productivity improvements in manufacturing, including mass production of substructure component and optimized installation strategies

- Improved plant siting and operation to reduce plant-level energy losses, resulting in higher capacity factors

- More efficient O&M procedures combined with more reliable components to reduce annual average FOM costs

- Adoption of a wide range of innovative control, design, and material concepts that facilitate the high-level trends described above.

Utility-Scale PV

Representative Technology

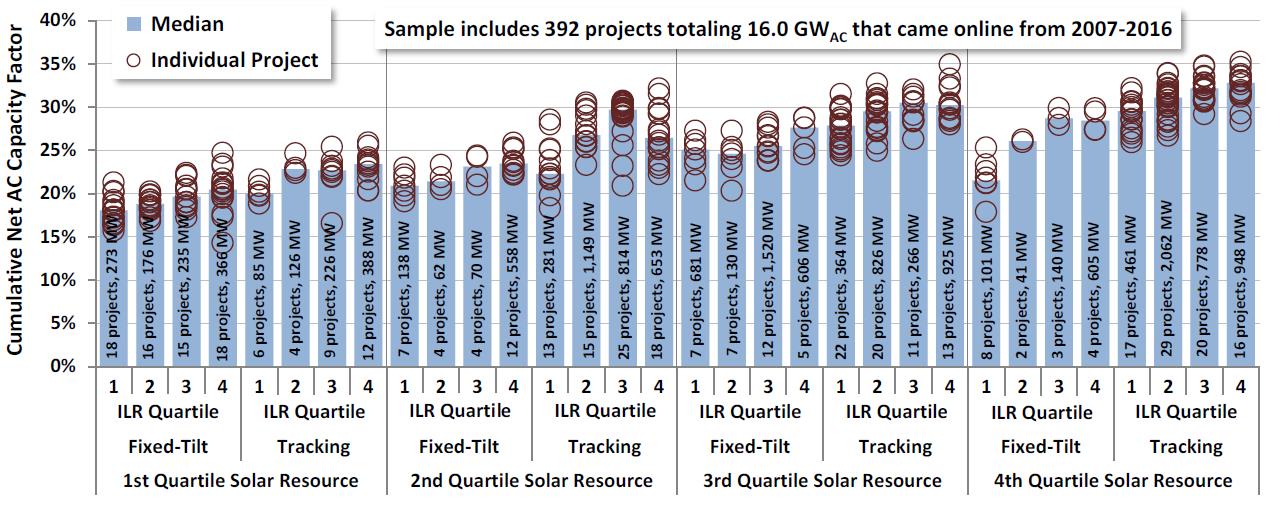

Utility-scale PV systems in the ATB are representative of one-axis tracking systems with performance and pricing characteristics in line with a 1.3 DC-to-AC ratio-or inverter loading ratio (ILR) (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018). PV system performance characteristics in previous ATB versions were designed in the ReEDS model at a time when PV system ILRs were lower than they are in current system designs; performance and pricing in the 2019 ATB incorporates more up-to-date system designs and therefore assumes a higher ILR.

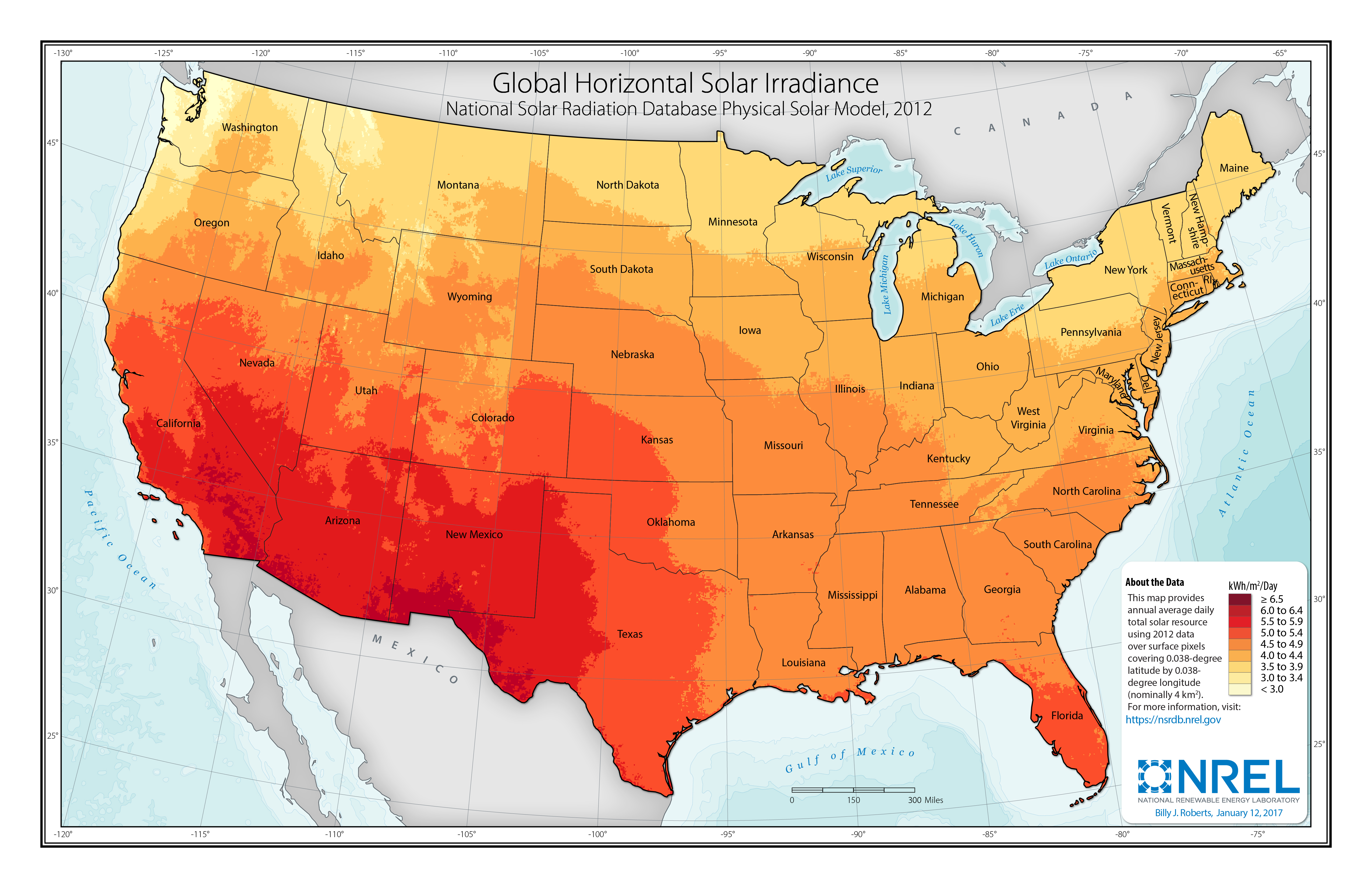

Resource Potential

Solar resources across the United States are mostly good to excellent at about 1,000-2,500 kWh/m2/year. The Southwest is at the top of this range, while Alaska and part of Washington are at the low end. The range for the contiguous United States is about 1,350-2,500 kWh/m2/year. Nationwide, solar resource levels vary by about a factor of two.

The total U.S. land area suitable for PV is significant and will not limit PV deployment. One estimate (Denholm and Margolis 2008) suggests the land area required to supply all end-use electricity in the United States using PV is about 5,500,000 hectares (ha) (13,600,000 acres), which is equivalent to 0.6% of the country's land area or about 22% of the "urban area" footprint (this calculation is based on deployment/land in all 50 states).

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012), represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential – resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

The Base Year estimates rely on modeled CAPEX and O&M estimates benchmarked with industry and historical data. Capacity factor is estimated based on hours of sunlight at latitude for five representative geographic locations in the United States. The ATB presents capacity factor estimates that encompass a range associated with Low, Mid, and Constant technology cost scenarios across the United States.

Future year projections are derived from analysis of published projections of PV CAPEX and bottom-up engineering analysis of O&M costs. Three different projections were developed for scenario modeling as bounding levels:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no change in CAPEX, O&M, or capacity factor from 2017 to 2050; consistent across all renewable energy technologies in the ATB

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: based on the median of literature projections of future CAPEX; O&M technology pathway analysis

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: based on the low bound of literature projections of future CAPEX and O&M technology pathway analysis.

Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year. These expenditures include the hardware, the balance of system (e.g., site preparation, installation, and electrical infrastructure), and financial costs (e.g., development costs, onsite electrical equipment, and interest during construction) and are detailed in CAPEX Definition. In the ATB, CAPEX reflects typical plants and does not include differences in regional costs associated with labor, materials, taxes, or system requirements. The related Standard Scenarios product uses Regional CAPEX Adjustments. The range of CAPEX demonstrates variation with resource in the contiguous United States.

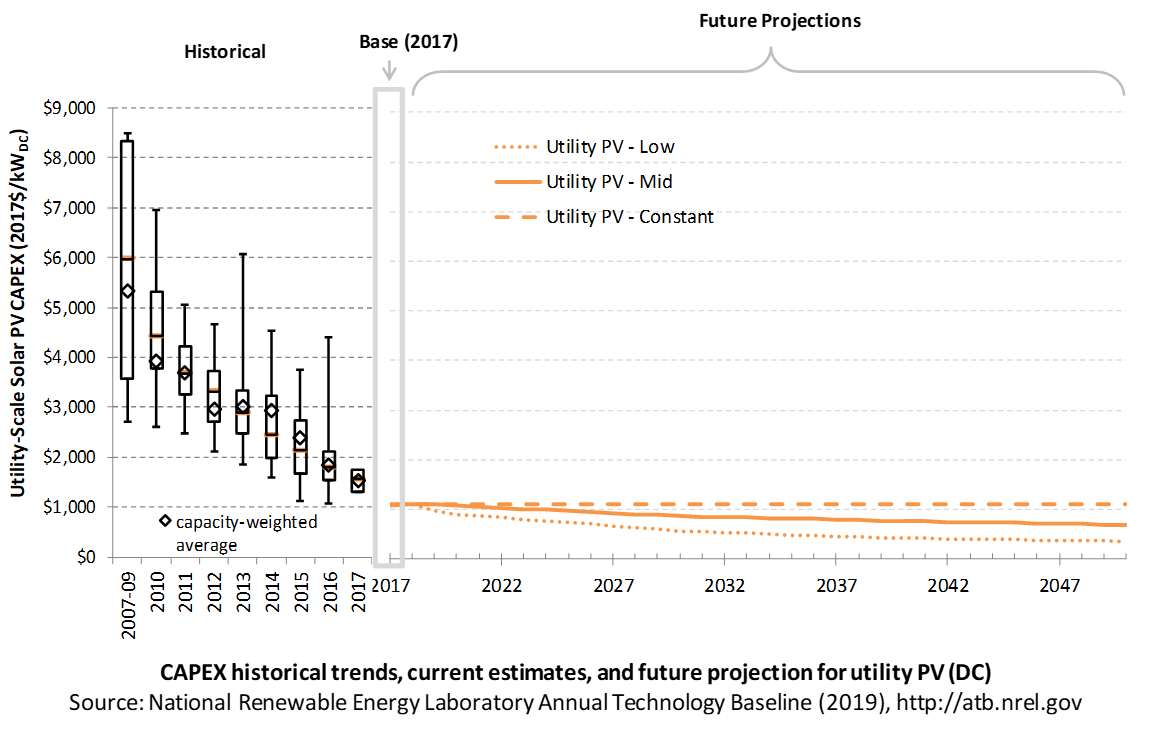

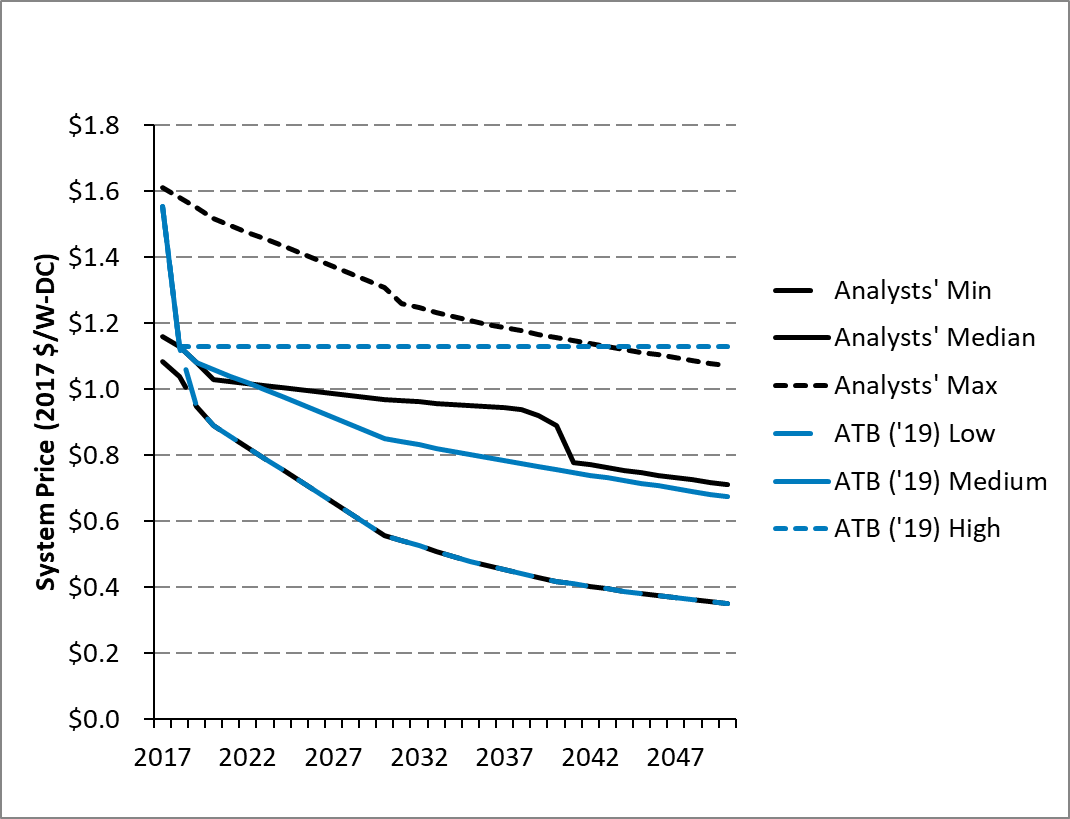

The following figures show the Base Year estimate and future year projections for CAPEX costs in terms of $/kWDC or $/kWAC. Three cost scenarios are represented: Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost. Historical data from utility-scale PV plants installed in the United States are shown for comparison to the ATB Base Year estimates. The estimate for a given year represents CAPEX of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

The PV industry typically refers to PV CAPEX in terms of $/kWDC based on the aggregated module capacity. The electric utility industry typically refers to PV CAPEX in terms of $/kWAC based on the aggregated inverter capacity. See Solar PV AC-DC Translation for details. The figures illustrate the CAPEX historical trends, current estimates, and future projections in terms of $/kWDC or $/kWAC; current estimates and future projections assume an inverter loading ratio of 1.3 while historical numbers represent reported values.

Recent Trends

Reported historical utility-scale PV plant CAPEX (Bolinger and Seel 2018) is shown in box-and-whiskers format for comparison to the historical benchmarked utility-scale PV plant overnight capital cost (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018) and future CAPEX projections. Bolinger and Seel (2018) provide statistical representation of CAPEX for 88% of all utility-scale PV capacity.

The difference in each year's price between the market and benchmark data reflects differences in methodologies. There are a variety of reasons reported and benchmark prices can differ, as enumerated by Barbose and Dargouth (2018) and Bolinger and Seel (2018) , including:

- Timing-related issues: For instance, the time between PPA contract completion date and project placed in service may vary, and a system can be reported as installed in separate sections over time or when an entire complex is complete. For example, in 2014, the reported capacity-weighted average system price was higher than 80% of system prices in 2014 due to very large systems, with multiyear construction schedules, installed in that year. Developers of these large systems negotiated contracts and installed portions of their systems when module and other costs were higher.

- Variations over time in the size, technology, installer margin, and design of systems installed in a given year

- Which cost categories are included in CAPEX (e.g., financing costs and initial O&M expenses).

Due to the investment tax credit, projects are encouraged to include as many costs incurred in the upfront CAPEX to receive a higher tax credit, which may have otherwise been reported as operating costs. The bottom-up benchmarks are more reflective of an overnight capital cost, which is in line with the ATB methodology of inputting overnight capital cost and calculating construction financing to derive CAPEX.

PV pricing and capacities are quoted in kWDC (i.e., module rated capacity) unlike other generation technologies, which are quoted in kWAC. For PV, this would correspond to the combined rated capacity of all inverters. This is done because kWDC is the unit that most of the PV industry uses. Although costs are reported in kWDC, the total CAPEX includes the cost of the inverter, which has a capacity measured in kWAC.

CAPEX estimates for 2019 reflect continued rapid decline supported by analysis of recent power purchase agreement pricing (Bolinger and Seel 2018) for projects that will become operational in 2019 and beyond.

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, a representative utility-scale PV plant is shown. Although the PV technologies vary, typical plant costs are represented with a single estimate because the CAPEX does not vary with solar resource.

Although the technology market share may shift over time with new developments, the typical plant cost is represented with the projections above.

A system price of $1.10/WDC in 2017 is based on modeled pricing for a 100-MWDC, one-axis tracking systems quoted in Q1 2018 as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018) , adjusted for inflation. The $1.10/WDC price in 2018 is based on modeled pricing for a 100-MWDC, one-axis tracking systems quoted in Q1 2018 as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018) , adjusted for inflation. The 2017 and 2018 bottom-up benchmarks are reflective of an overnight capital cost, which is in line with the ATB methodology of inputting overnight capital cost and calculating construction financing to derive CAPEX. We focus on larger systems for the 2017 and 2018 values to better align with the current trends in utility-scale installations. EIA (2019) reported that 94 PV installations totaling 4.3 GWAC were placed in service in 2018 in the United States. While this represents an average of approximately 46 MWAC, 78% of the installed capacity in 2018 came from systems greater than 50 MWAC, and 38% from systems greater than 100 MWAC. Regardless, both 2017 and 2018 figures are in line with other estimated system prices reported by Feldman and Margolis (2018) .

Future Year Projections

Projections of future utility-scale PV plant CAPEX are based on 11 system price projections from 9 separate institutions. Projections include:

- Short-term projections made in the past two years: (Avista 2017), (BNEF 2018), (E3 2017), (GTM Research 2018), and (IEA 2018)

- Long-term projections made in the last three years: (ABB 2017), (BNEF 2017), (EIA 2019b), (EIA 2018), (IEA 2018c), (IRENA 2016), and (Lam, Branstetter, and Azevedo 2018) .

We adjusted the "min," "median," and "max" projections in a few

different ways. All 2017 and 2018 pricing are based on the bottom-up

benchmark analysis reported in U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System

Cost Benchmark Q1 2018

We adjusted the Mid and Low projections for 2019-2050 to remove distortions caused by the combination of forecasts with different time horizons and based on internal judgment of price trends. Without such adjustments, the Mid and Low projections would have increased over time in certain years, or they would have decreased dramatically due to the end of a projection's timeline. The Constant cost scenario is kept constant at the 2018 CAPEX value and assumes no improvements beyond 2018.

The largest annual reductions in CAPEX for the Low projection occur from 2018 to 2019, dropping 14%, which is on par with the average reduction in reported price of 14% between 2010 and 2017 (Bolinger and Seel 2018) . Initial reported pricing for utility-scale power purchase agreements (PPAs) placed in service in 2018 fell to approximately $42/MWh (Real $2018), which is consistent in price with PPAs executed in 2015 and 2016, representing a two- to three-year lag from execution to installation. Looking forward, the capacity average executed PPA price for a provisional set of U.S. projects in 2018 was approximately $23/MWh (Real $2018). If PPAs executed in 2018 follow a similar two-year lag, we would expect those systems to be installed in 2020-2021; therefore, we could see the capacity-weighted average PPA price for systems installed in the year fall from $42/MWh in 2018 to $23/MWh in 2020, or 46% less. The capacity average executed PPA price in 2017 was 15% lower than the capacity-weighted average PPA price for a system installed in 2017. PPA pricing and CAPEX are not perfectly correlated-annual reductions of PPA and CAPEX only have a correlation coefficient of 0.17 from 2010 to 2017; however, the correlation coefficient for reduction over a four-year period in PPA and CAPEX during that time (i.e., PPA or CAPEX reduction from 2010 to 2014, 2011 to 2015, 2012 to 2016, and 2013 to 2017) was 0.95 – from 2010 to 2017, the capacity-weighted average PPA price and CAPEX for systems installed in that year fell 69% and 61% respectively (Bolinger and Seel 2018) .

Looking to 2030 and beyond, various technical, market, and business improvements could significantly reduce PV system costs further, in line with the low and mid CAPEX projections. Many manufacturers have near-term road maps that will greatly exceed the 18.1% module efficiency assumed in the 2018 utility-scale overnight capital cost benchmark; for example, Canadian Solar reported that its mass produced cells will increase 20%-22% in 2018 (depending on cell line) to 22%-24% by 2021 (Canadian Solar 2019) . However, greater efficiencies can still be achieved if the industry can translate gains in the laboratory to mass production, as the current monocrystalline cell efficiency record in a laboratory is 26.1% (EIA 2016a) and (NREL: "Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart"). Additionally, the industry also has the potential to significantly increase cell efficiencies by using double junction cell technology; for example, perovskite on top of c-Si has a theoretical maximum efficiency of 44% (Fuscher and Bruno 2016) .

Other factors are also expected to significantly decrease PV system

prices. For example, at the end of 2018, the global module price was

approximately $0.22/W

(Feldman and Margolis 2018)

compared to the 2018 utility-scale CAPEX benchmark, which assumes a

module price of $0.47/W

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future CAPEX costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

For the ATB, and based on EIA (2016a) and the NREL Solar PV Cost Model (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018), the utility-scale solar PV plant envelope is defined to include:

- Hardware

- Module supply

- Power electronics, including inverters

- Racking

- Foundation

- AC and DC wiring materials and installation

- Electrical infrastructure, such as transformers, switchgear, and electrical system connecting modules to each other and to the control center

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Land acquisition, site preparation, installation of underground utilities, access roads, fencing, and buildings for operations and maintenance

- Project indirect costs, including costs related to engineering, distributable labor and materials, construction management start up and commissioning, and contractor overhead costs, fees, and profit

- Financial Costs

- Owners' costs, such as development costs, preliminary feasibility and engineering studies, environmental studies and permitting, legal fees, insurance costs, and property taxes during construction

- Electrical interconnection, including onsite electrical equipment (e.g., switchyard), a nominal-distance spur line (< 1 mile), and necessary upgrades at a transmission substation; distance-based spur line cost (GCC) not included in the ATB

- Interest during construction estimated based on six-month duration accumulated 100% at half-year intervals and an 8% interest rate (ConFinFactor).

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

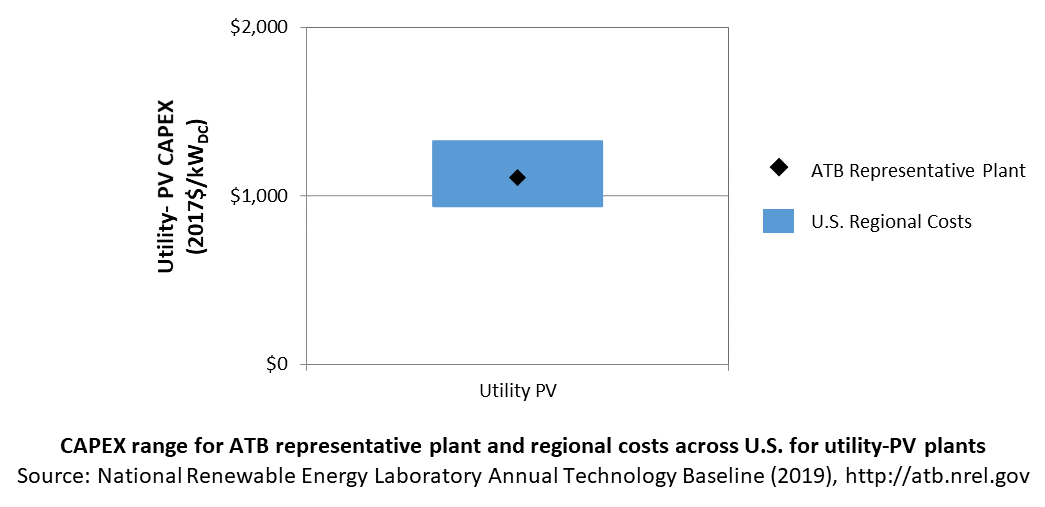

In the ATB, CAPEX represents a typical one-axis utility-scale PV plant and does not vary with resource. The difference in cost between tracking and non-tracking systems has been reduced greatly in the United States. Regional cost effects associated with labor rates, material costs, and other regional effects as defined by EIA (2016b) expand the range of CAPEX. Unique land-based spur line costs based on distance and transmission line costs for potential utility-PV plant locations expand the range of CAPEX even further. The following figure illustrates the ATB representative plant relative to the range of CAPEX including regional costs across the contiguous United States. The ATB representative plants are associated with a regional multiplier of 1.0.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

CAPEX in the ATB does not represent regional variants (CapRegMult) associated with labor rates, material costs, etc., but the ReEDS model does include 134 regional multipliers (EIA 2016b).

CAPEX in the ATB does not include a geographically determined spur line (GCC) from plant to transmission grid, but the ReEDS model calculates a unique value for each potential PV plant.

Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent the annual fixed expenditures required to operate and maintain a solar PV plant over its lifetime, including:

- Insurance, property taxes, site security, legal and administrative fees, and other fixed costs

- Present value and annualized large component replacement costs over technical life (e.g., inverters at 15 years)

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of solar PV plants, transformers, etc. over the technical lifetime of the plant (e.g., general maintenance, including cleaning and vegetation removal).

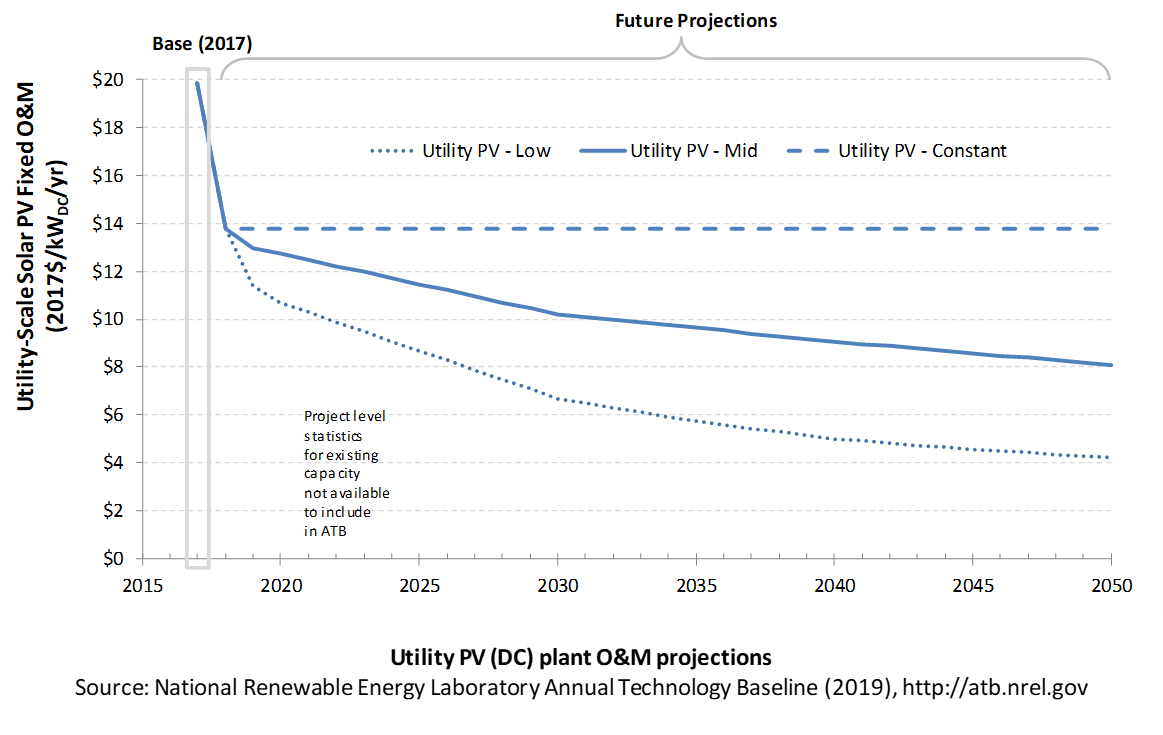

The following figure shows the Base Year estimate and future year projections for fixed O&M (FOM) costs. Three cost scenarios are represented. The estimate for a given year represents annual average FOM costs expected over the technical lifetime of a new plant that reaches commercial operation in that year.

Base Year Estimates

FOM of $20/kWDC - yr is based on modeled pricing for a 100-MWDC, one-axis tracking systems quoted in Q1 2017 as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018), adjusted for inflation. The values in this report (ATB 2019) are higher than those from ATB 2018 because they better align with the benchmarks reported in Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018); the previous edition relied solely on an O&M-to-CAPEX ratio, derived from multiple reports. A wide range in reported prices exists in the market, in part depending on the maintenance practices that exist for a particular system. These cost categories include asset management (including compliance and reporting for incentive payments), different insurance products, site security, cleaning, vegetation removal, and failure of components. Not all these practices are performed for each system; additionally, some factors depend on the quality of the parts and construction. NREL analysts estimate O&M costs can range from $0 to $40/kWDC - yr.

Future Year Projections

FOM for 2018 is also based on pricing reported in Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018), adjusted for inflation. From 2019-2050, FOM is based on the historical average ratio of O&M costs ($/kW-yr) to CAPEX costs ($/kW), 1.2:100, as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018). This ratio is higher than the ratio of O&M costs to historically reported CAPEX costs of 0.7:100, which are derived from 2011 to 2017 historical data reported by Bolinger and Seel (2018), as well as the ratio of O&M costs to CAPEX costs of 1.0:100, which is derived from (IEA 2016) and (Lazard 2018). Historically reported data suggest O&M and CAPEX cost reductions are correlated; from 2011 to 2017, fleetwide average O&M and CAPEX costs fell 50% and 58% respectively, as reported by Bolinger and Seel (2018).

A detailed description of the methodology for developing future year projections is found in Projections Methodology.

Technology innovations that could impact future O&M costs are summarized in LCOE Projections.

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

The capacity factor represents the expected annual average energy production divided by the annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. It is intended to represent a long-term average over the lifetime of the plant. It does not represent interannual variation in energy production. Future year estimates represent the estimated annual average capacity factor over the technical lifetime of a new plant installed in a given year.

Other technologies' capacity factors are represented in exclusively AC units; however, because PV pricing in this ATB documentation is represented in $/kWDC, PV system capacity is a DC rating. The PV capacity factor is the ratio of annual average energy production (kWhAC) to annual energy production assuming the plant operates at rated DC capacity for every hour of the year. For more information, see Solar PV AC-DC Translation.

The capacity factor is influenced by the hourly solar profile, technology (e.g., thin-film versus crystalline silicon), axis type (e.g., none, one, or two), expected downtime, and inverter losses to transform from DC to AC power. The DC-to-AC ratio is a design choice that influences the capacity factor. PV plant capacity factor incorporates an assumed degradation rate of 0.75%/year (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018)in the annual average calculation. R&D could lower degradation rates of PV plant capacity factor; future projections for Mid and Low cost scenarios reduce degradation rates by 2050, using a straight-line basis, to 0.5%/year and 0.2%/year respectively.

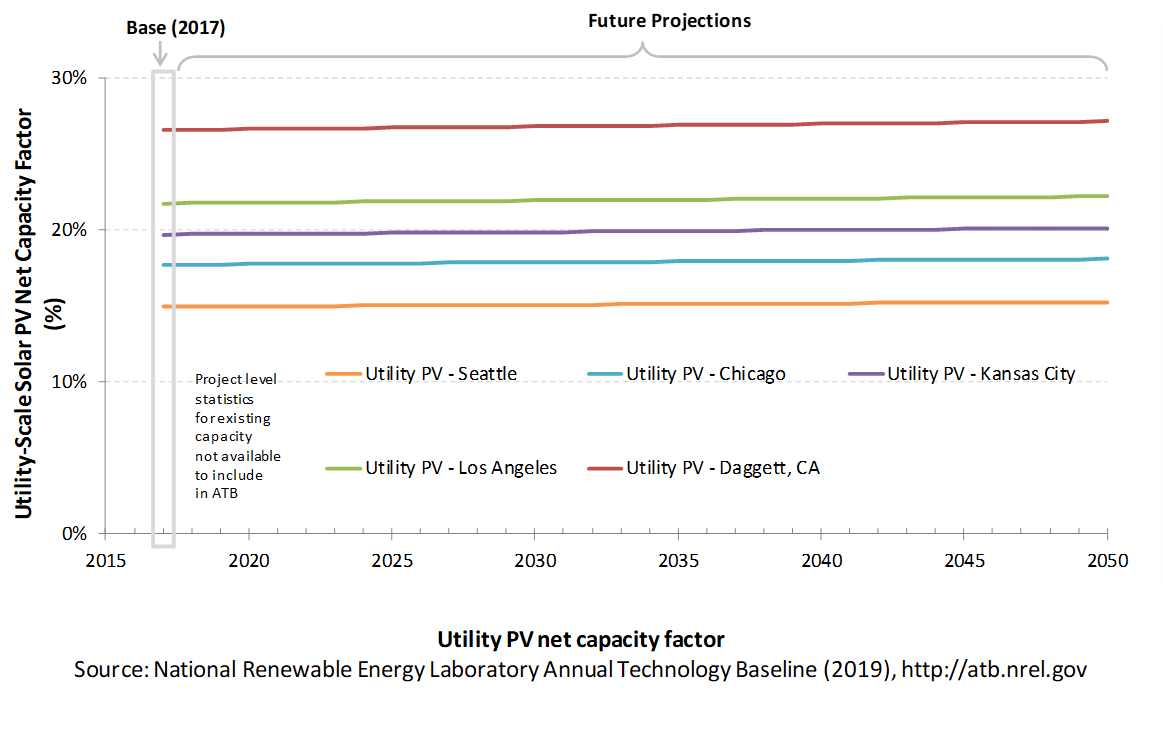

The following figure shows a range of capacity factors based on variation in solar resource in the contiguous United States. The range of the Base Year estimates illustrate the effect of locating a utility-scale PV plant in places with lower or higher solar irradiance. These five values use specific locations as examples of high (Daggett, California), high-mid (Los Angeles, California), mid (Kansas City, Missouri), low-mid (Chicago, Illinois), and low (Seattle, Washington) resource areas in the United States as implemented in the System Advisor Model using PV system characteristics from Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (2018).

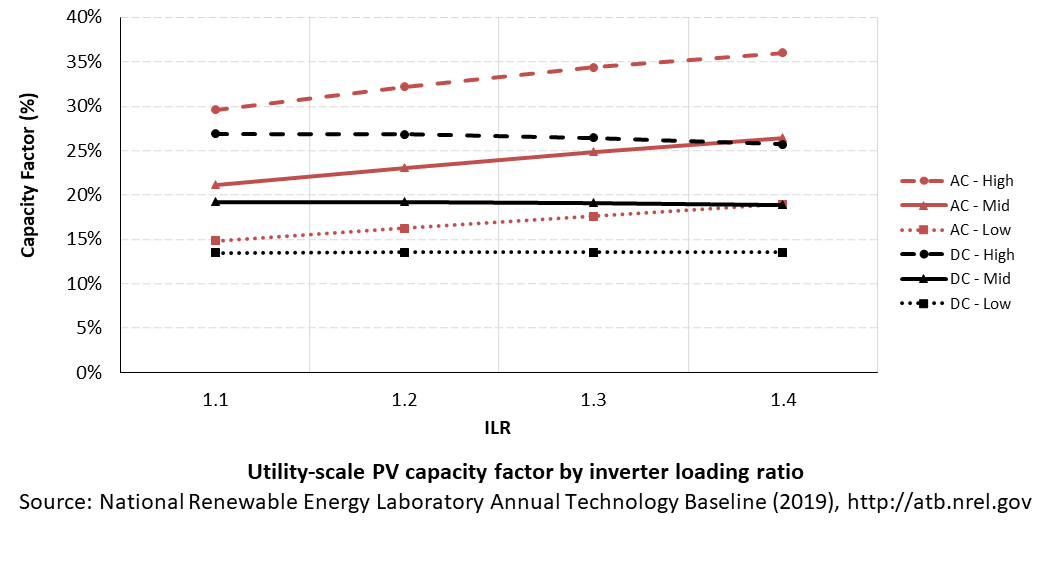

PV system inverters, which convert DC energy/power to AC energy/power, have AC capacity ratings; therefore, the capacity of a PV system is rated in MWAC, or the aggregation of all inverters' rated capacities, or MWDC, or the aggregation of all modules' rated capacities. The capacity factor calculation uses a system's rated capacity, and therefore, capacity factor can be represented using exclusively AC units or using AC units for electricity (the numerator) and DC units for capacity (the denominator). Both capacity factors will result in the same LCOE as long as the other variables use the same capacity rating (e.g., CAPEX in terms of $/kWDC). PV systems' DC ratings are typically higher than their AC ratings; therefore, the capacity factor calculated using a DC capacity rating has a higher denominator. In the ATB, we use capacity factors of 15.9%, 18.9%, 21.0%, 23.2%, and 28.3% for the first year of a PV project and adjust the values to reflect an average capacity factor for the lifetime of a project, calculated with MWDC, assuming 0.75% module capacity degradation per year in the Base Year and declining to 0.5% and 0.2% module capacity degradation per year by 2050 for the Mid and Low cost scenarios. The adjusted average capacity factor values used in the ATB Base Year are 14.9%, 17.7%, 19.7%, 21.7%, and 26.6%. These numbers would change to approximately 19.4%, 23.0%, 25.6%, 29.3%, and 34.5% if the ATB used MWAC. The following figure illustrates capacity factor – both DC and AC – for a range of inverter loading ratios for the Base Year. The ATB capacity factor assumptions are based on ILR = 1.3.

Recent Trends

At the end of 2017, the capacity-weighted average AC capacity factor for all U.S. projects installed at the time was 26.0% (including fixed-tilt systems), but individual project-level capacity factors exhibited a wide range (14.3%-35.2%).

The capacity-weighted average capacity factor was more closely in line with the higher end of the range because 55% of installed capacity from the data set was placed in service in the past two years of when the data were collected (and therefore have not degraded substantially), and 67% of the installed capacity was in the southwestern United States or California, where the average capacity factor was 29.8% for one-axis systems and 25.2% for fixed-tilt systems (Bolinger and Seel 2018).

Base Year Estimates

For illustration in the ATB, a range of capacity factors associated with the range of latitude in the contiguous United States is shown.

Over time, PV plant output is reduced. This degradation (at 0.75%) is accounted for in ATB estimates of capacity factor. The ATB capacity factor estimates represent estimated annual average energy production over a 30-year lifetime.

These DC capacity factors are for a one-axis tracking system with a DC-to-AC ratio of 1.3.

Future Year Projections

Projections of capacity factors for plants installed in future years are unchanged from the Base Year for the Constant cost scenario. Capacity factors for Mid and Low cost scenarios are projected to increase over time, caused by a straight-line reduction in PV plant capacity degradation rates from 0.75%, reaching 0.5%/year and 0.2%/year by 2050 for the Mid and Low cost scenarios respectively. The following table summarizes the difference in average capacity factor in 2050 caused by different degradation rates in the Constant, Mid, and Low cost scenarios.

| Seattle, WA | Chicago, IL | Kansas City, MO | Los Angeles, CA | Daggett, CA | |

| Low Cost (0.30% degradation rate) | 15.5% | 18.4% | 20.5% | 22.6% | 27.6% |

| Mid Cost (0.50% degradation rate) | 15.2% | 18.1% | 20.1% | 22.2% | 27.1% |

| Constant Cost (0.75% degradation rate) | 14.9% | 17.7% | 19.7% | 21.7% | 26.6% |

Solar PV plants have very little downtime, inverter efficiency is already optimized, and tracking is already assumed. That said, there is potential for future increases in capacity factors through technological improvements beyond lower degradation rates, such as less panel reflectivity and improved performance in low-light conditions.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

The ReEDS model output capacity factors for wind and solar PV can be lower than input capacity factors due to endogenously estimated curtailments determined by system operation.

Plant Cost and Performance Projections Methodology

Currently, CAPEX – not LCOE – is the most common metric for PV cost. Due to differing assumptions in long-term incentives, system location and production characteristics, and cost of capital, LCOE can be confusing and often incomparable between differing estimates. While CAPEX also has many assumptions and interpretations, it involves fewer variables to manage. Therefore, PV projections in the ATB are driven primarily by CAPEX cost improvements, along with minor improvements in operational cost and cost of capital.

The Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost cases explore the range of possible outcomes of future PV cost improvements:

- Constant Technology Cost Scenario: no improvements made beyond today

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: current expectations of price reductions in a "business-as-usual" scenario

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: expectations of potential cost reductions given improved R&D funding, favorable financing, and more aggressive global deployment targets.

While CAPEX is one of the drivers to lower costs, R&D efforts continue to focus on other areas to lower the cost of energy from utility-scale PV, such as longer system lifetime and improved performance.

Projections of future utility-scale PV plant CAPEX are based on 11 system price projections from 9 separate institutions. The short-term forecasts were primarily provided by market analysis firms with expertise in the PV industry, through a subscription service with NREL. The long-term forecasts primarily represent the collection of publicly available, unique forecasts with either a long-term perspective of solar trends or through capacity expansion models with assumed learning by doing. Short-term U.S. price forecasts made in the past two years include: (Avista 2017), (BNEF 2018), (E3 2017), (GTM Research 2018), and (IEA 2018b). Long-term projections made in the past three years include (ABB 2017), (BNEF 2017), (EIA 2019b), (IEA 2018a), (IRENA 2016), and (Lam, Branstetter, and Azevedo 2018).

- Short-Term Forecast Institutions: Avista, Bloomberg New Energy Finance, CAISO, GTM Research, International Energy Agency

- Long-Term Forecast Institutions: ABB; Bloomberg New Energy Finance; International Energy Agency; IRENA; Lam, Branstetter, and Azevedo (2018); U.S. Energy Information Administration.

To adjust all projections to the ATB's assumption of single-axis tracking systems, 7% was added to all price projections that assumed fixed-tilt tracking technology, and 3.5% was added for all price projections that did not list whether the technology was fixed-tilt or single-axis tracking. All price projections quoted in $/WAC were converted to $/WDC using a 1.3 ILR. In instances in which literature projections did not include all years, a straight-line change in price was assumed between any two projected values. To generate Mid and Low technology cost scenarios, we took the "median" and "min" of the data sets; however, we only included short-term U.S. forecasts until 2030 as they focus on near-term pricing trends within the industry. Starting in 2030, we include long-term global and U.S. forecasts in the data set, as they focus more on long-term trends within the industry. It is also assumed that after 2025, U.S. prices will be on par with global averages; the federal tax credit for solar assets reverts down to 10% for all projects placed in service after 2023, which has the potential to lower upfront financing costs and remove any distortions in reported pricing, compared to other global markets. Additionally, a larger portion of the United States will have a more mature PV market, which should result in a narrower price range. Changes in price for the Mid and Low technology cost scenarios between 2020 and 2030 are interpolated on a straight-line basis.

We adjusted the "median" and "min" projections in a few different ways. All 2017 and 2018 pricing are based on the bottom-up benchmark analysis reported in U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System Cost Benchmark Q1 2018 (adjusted for inflation)(Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018). These figures are in line with other estimated system prices reported in Q2/Q3 2018 Solar Industry Update (Feldman and Margolis 2018).

We adjusted the Mid and Low projections for 2019-2050 to remove distortions caused by the combination of forecasts with different time horizons and based on internal judgment of price trends. The Constant technology cost scenario is kept constant at the 2018 CAPEX value, assuming no improvements beyond 2018.

We derive future FOM based on the historical average ratio of O&M costs ($/kW-yr) to CAPEX costs ($/kW), 1.2:100, as reported by Fu, Feldman, and Margolis (Fu, Feldman, and Margolis 2018). Historically reported data suggest O&M and CAPEX cost reductions are correlated; from 2011 to 2017 fleetwide average O&M and CAPEX costs fell 50% and 58% respectively, as reported by Bolinger and Seel (2018).

O&M cost reductions are likely to be achieved over the next decade by a transition from manual and reactive O&M to semi-automated and fully automated O&M where possible. While many of these tasks are very site and region specific, emerging technologies have the potential to reduce the total O&M costs across all systems. For example, automated processes of sensors, monitors, remote-controlled resets, and drones to perform operations have the potential to allow O&M on PV systems to operate more efficiently at lower cost. Not all tasks have a clear path of automation due to complexity, safety, and some policy. This is one reason some level of manual interventions will likely exist for quite some time. Also, as systems age, O&M tasks that rely strictly on manpower are likely to increase in cost over the system lifetime.

Projections of capacity factors for plants installed in future years are unchanged from 2018 for the Constant cost scenario. Capacity factors for Mid and Low cost scenarios are projected to increase over time, caused by a straight-line reduction in PV plant capacity degradation rates, reaching 0.5%/year and 0.2%/year by 2050 for the Mid and Low cost scenarios respectively.

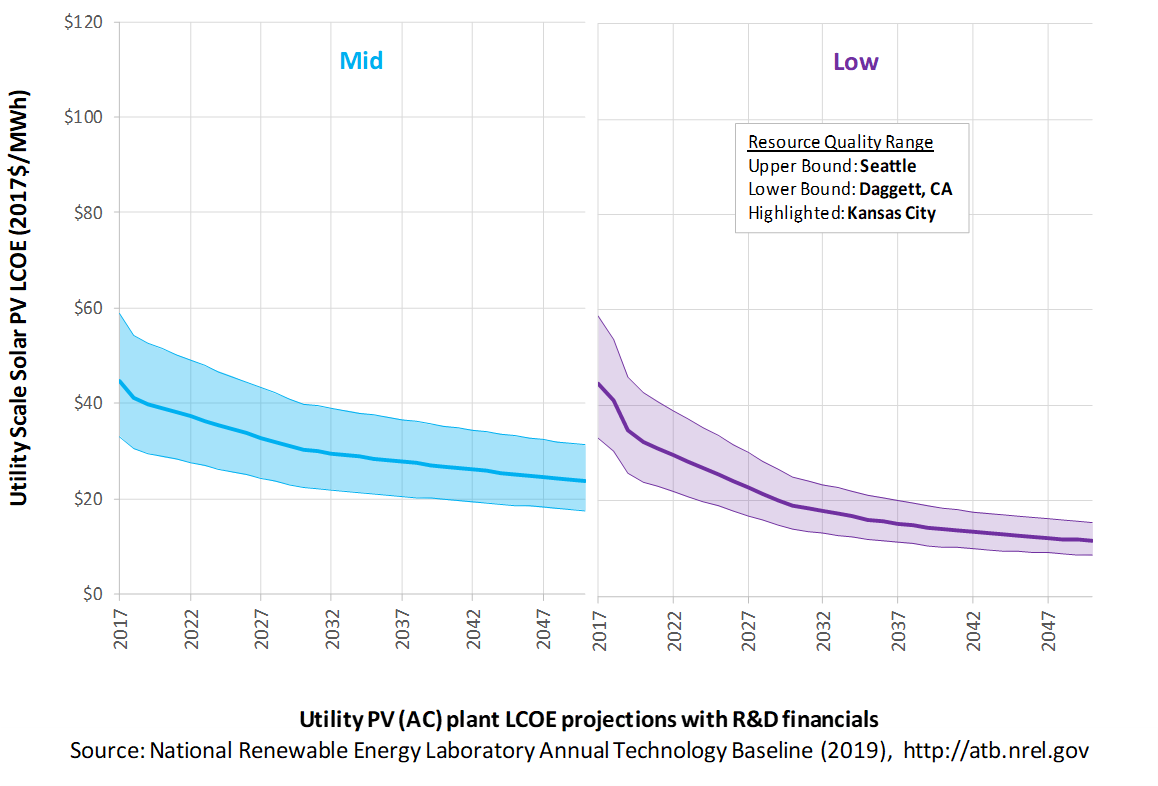

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a summary metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

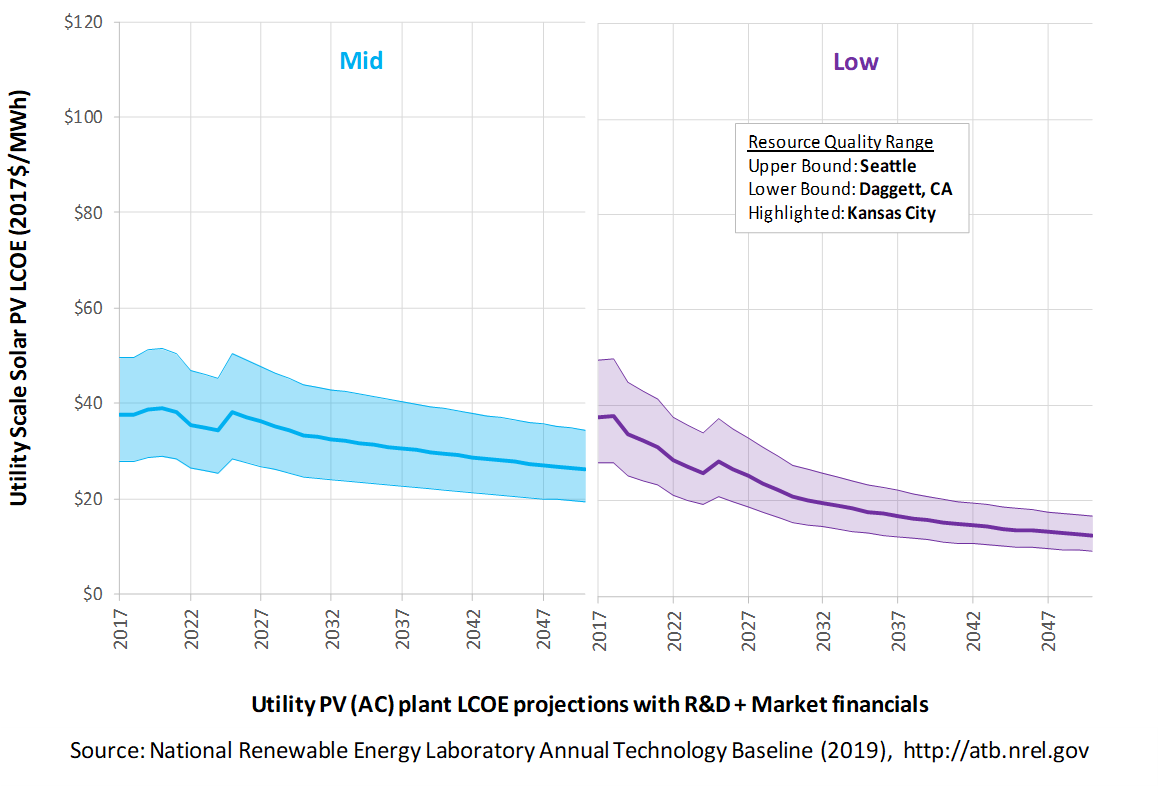

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for utility-scale PV across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs but not in the upfront capital costs (e.g., developer fees and contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside of the United States, due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g., offshore wind in Europe) or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these financial assumptions: (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform and tax credits. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term utility-scale PV plants are associated with Utility PV: Kansas City. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB Data spreadsheet; for simplicity, not all resource categories are shown in the figures. In the R&D + Market LCOE case, there is an increase in LCOE from 2018-2020, caused by an increase WACC, and an increase from 2023-2024, caused by the reduction in tax credits.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The methodology for representing the CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions behind each pathway is discussed in Projections Methodology. In general, the degree of adoption of technology innovation distinguishes the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios. These projections represent trends that reduce CAPEX and improve performance. Development of these scenarios involves technology-specific application of the following general definitions:

- Constant Technology: Base Year (or near-term estimates of projects under construction) equivalent through 2050 maintains current relative technology cost differences

- Mid Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances through continued industry growth, public and private R&D investments, and market conditions relative to current levels that may be characterized as "likely" or "not surprising"

- Low Technology Cost Scenario: Technology advances that may occur with breakthroughs, increased public and private R&D investments, and/or other market conditions that lead to cost and performance levels that may be characterized as the " limit of surprise" but not necessarily the absolute low bound.

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation projects are required, and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Two project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2017 values from AEO2019 (EIA 2019b)and excludes effects of tax reform and tax credits.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO2019 as well as effects of tax reform, and tax credits. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE.

A constant cost recovery period – over which the initial capital investment is recovered – of 30 years is assumed for all technologies throughout this website, and can be varied in the ATB data spreadsheet.

The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the Equations and Variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2019 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

In general, differences among the technology cost cases reflect different levels of adoption of innovations. Reductions in technology costs reflect the cost reduction opportunities that are listed below.

- Modules

- Increased module efficiencies and increased production-line throughput to decrease CAPEX; overhead costs on a per-kilowatt basis will go down if efficiency and throughput improvement are realized

- Reduced wafer thickness or the thickness of thin-film semiconductor layers

- Development of new semiconductor materials

- Development of larger manufacturing facilities in low-cost regions

- Balance of system (BOS)

- Increased module efficiency, reducing the size of the installation

- Development of racking systems that enhance energy production or require less robust engineering

- Integration of racking or mounting components in modules

- Reduction of supply chain complexity and cost

- Creation of standard packaged system design

- Improvement of supply chains for BOS components in modules

- Improved power electronics

- Improvement of inverter prices and performance, possibly by integrating microinverters

- Decreased installation costs and margins

- Reduction of supply chain margins (e.g., profit and overhead charged by suppliers, manufacturer, distributors, and retailers); this will likely occur naturally as the U.S. PV industry grows and matures

- Streamlining of installation practices through improved workforce development and training and developing standardized PV hardware

- Expansion of access to a range of innovative financing approaches and business models

- Development of best practices for permitting interconnection and PV installation such as subdivision regulations, new construction guidelines, and design requirements.

FOM cost reduction represents optimized O&M strategies, reduced component replacement costs, and lower frequency of component replacement.

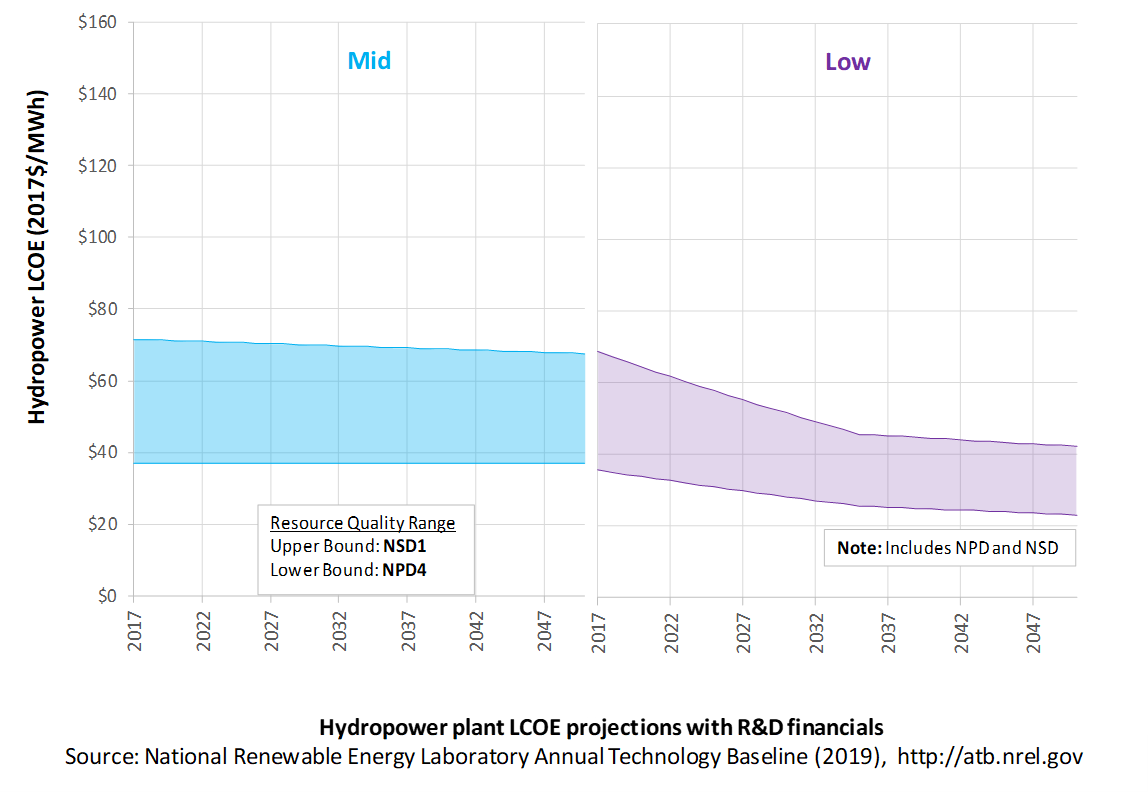

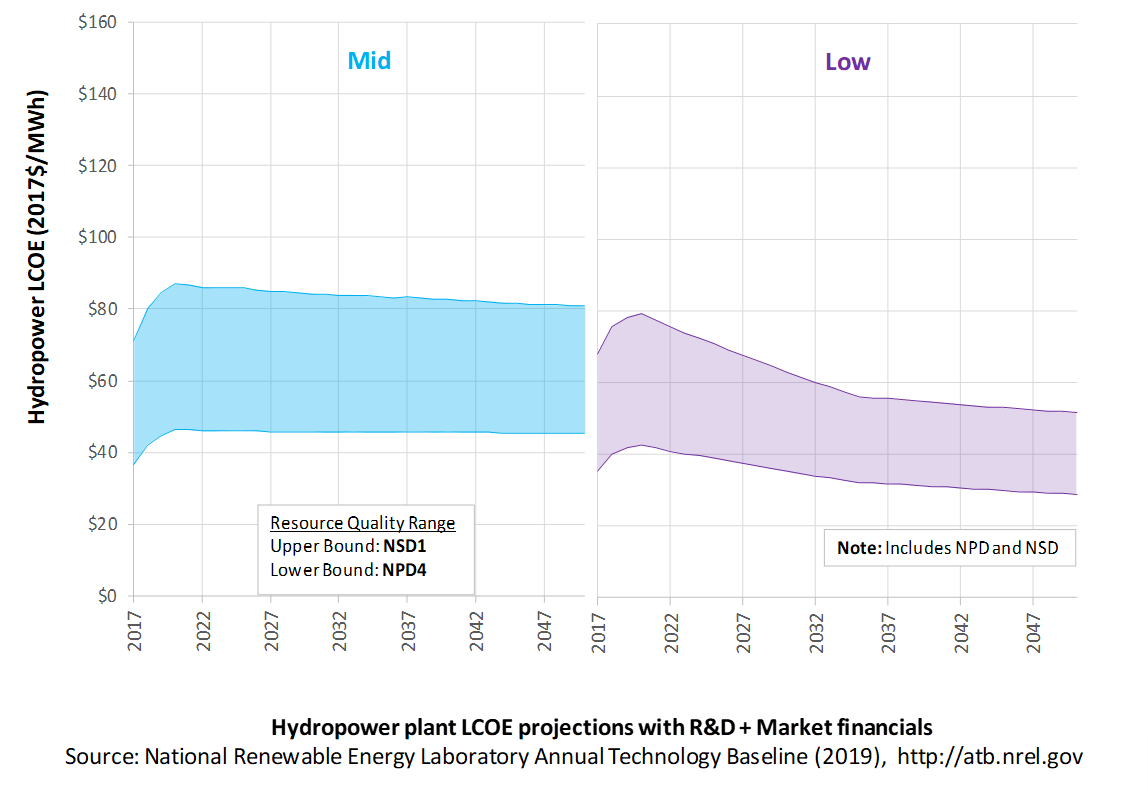

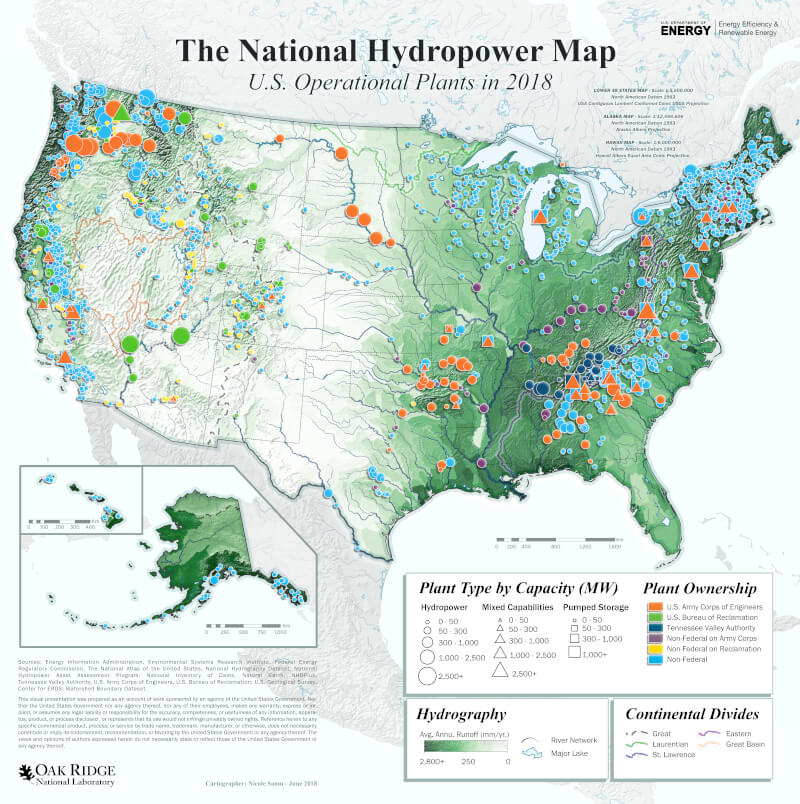

Hydropower

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. (2012) , represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. The primary benefit of assessing technical potential is that it establishes an upper-boundary estimate of development potential. It is important to understand that there are multiple types of potential-resource, technical, economic, and market (see NREL: "Renewable Energy Technical Potential").

Note: Pumped-storage hydropower is considered a storage technology in the ATB and will be addressed in future years. It and other storage technologies are represented in Standard Scenarios Model Results from the ReEDS model, and battery storage technologies are shown in the associated portion of the ATB.

Representative Technology

Hydropower technologies have produced electricity in the United States for over a century. Many of these infrastructure investments have potential to continue providing electricity in the future through upgrades of existing facilities (DOE, 2016) . At individual facilities, investments can be made to improve the efficiency of existing generating units through overhauls, generator rewinds, or turbine replacements. Such investments are known collectively as "upgrades," and they are reflected as increases to plant capacity. As plants reach a license renewal period, upgrades to existing facilities to increase capacity or energy output are typically considered. While the smallest projects in the United States can be as small as 10-100 kW, the bulk of upgrade potential is from large, multi-megawatt facilities.

Resource Potential

The estimated total upgrade potential of 6.9 GW/24 terawattt-hours (TWh) (at about 1,800 facilities) is based on generalizable information drawn from a series of case studies or owner-specific assessments (DOE, 2016) . Information available to inform the representation of improvements to the existing fleet includes:

- A systematic, full-fleet assessment of expansion potential at Reclamation projects performed under the Reclamation Hydropower Modernization Initiative (see U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, "Hydropower Resource Assessment at Existing Reclamation Facilities")

- Case study reports from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) performed under its Hydropower Modernization Initiative (MWH, Watson, & Harza, 2009)

- Case study reports combining assessments of upgrade and unit and plant optimization potential from the U.S. Department of Energy/Oak Ridge National Laboratory Hydropower Advancement Project.

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

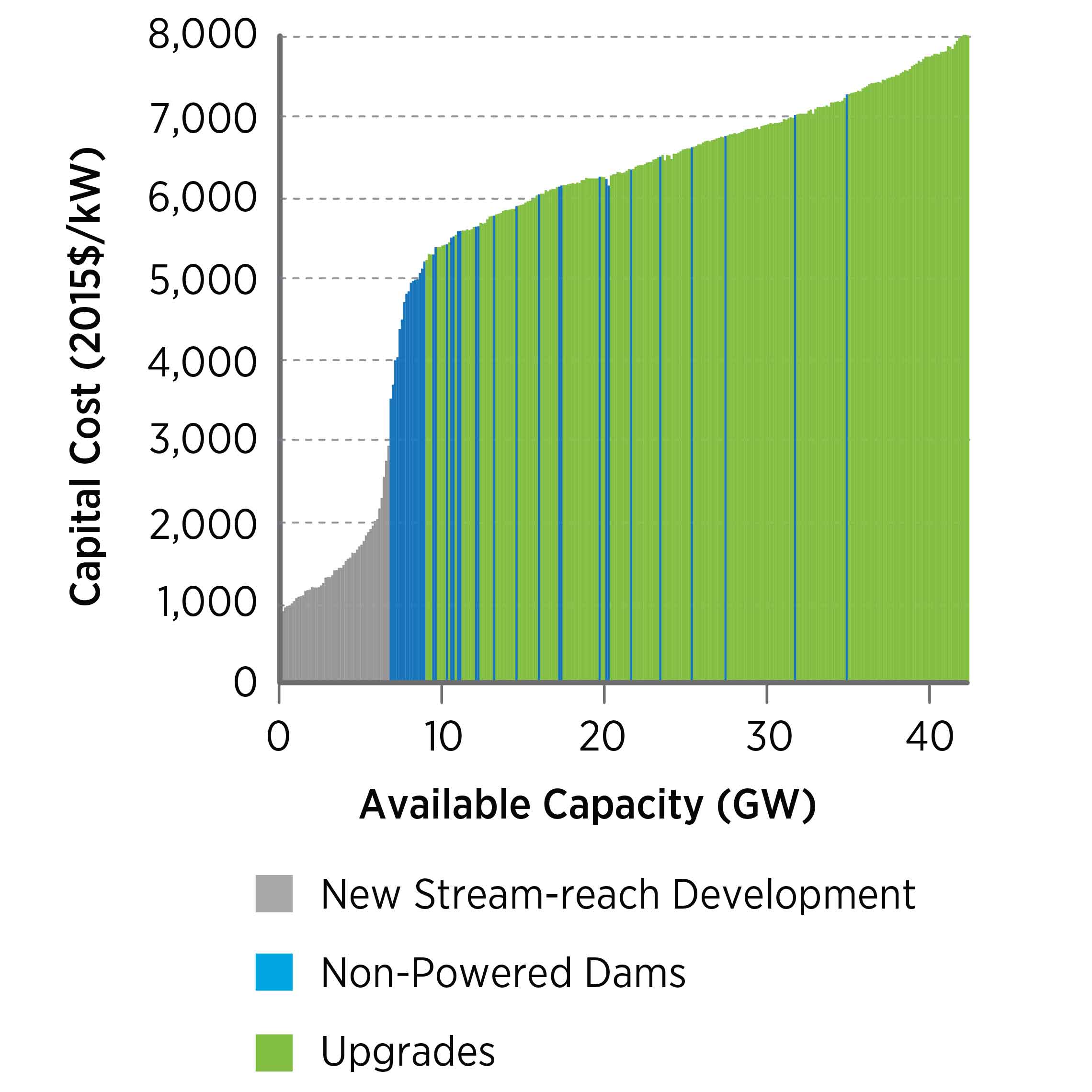

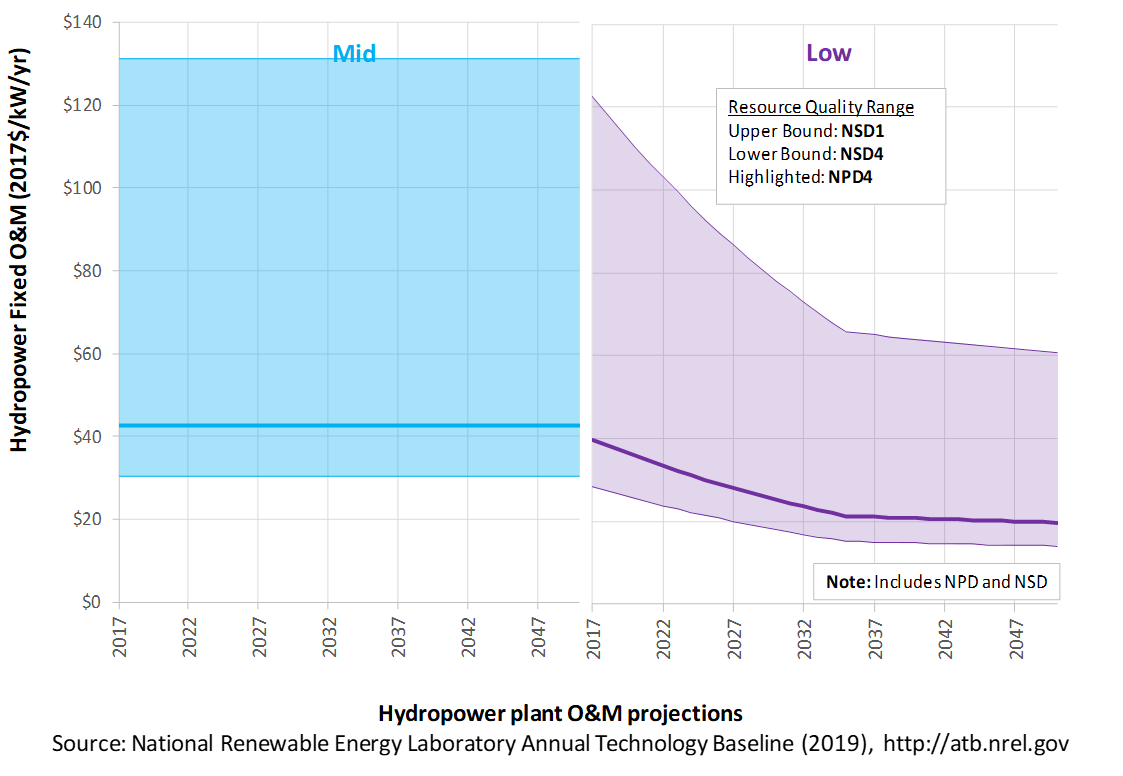

Upgrades are often among the lowest-cost new capacity resource, with the modeled costs for individual projects ranging from $800/kW to nearly $20,000/kW. This differential results from significant economies of scale from project size, wherein larger capacity plants are less expensive to upgrade on a dollar-per-kilowatt basis than smaller projects are. The average cost of the upgrade resource is approximately $1,500/kW.

CAPEX for each existing facility is based on direct estimates

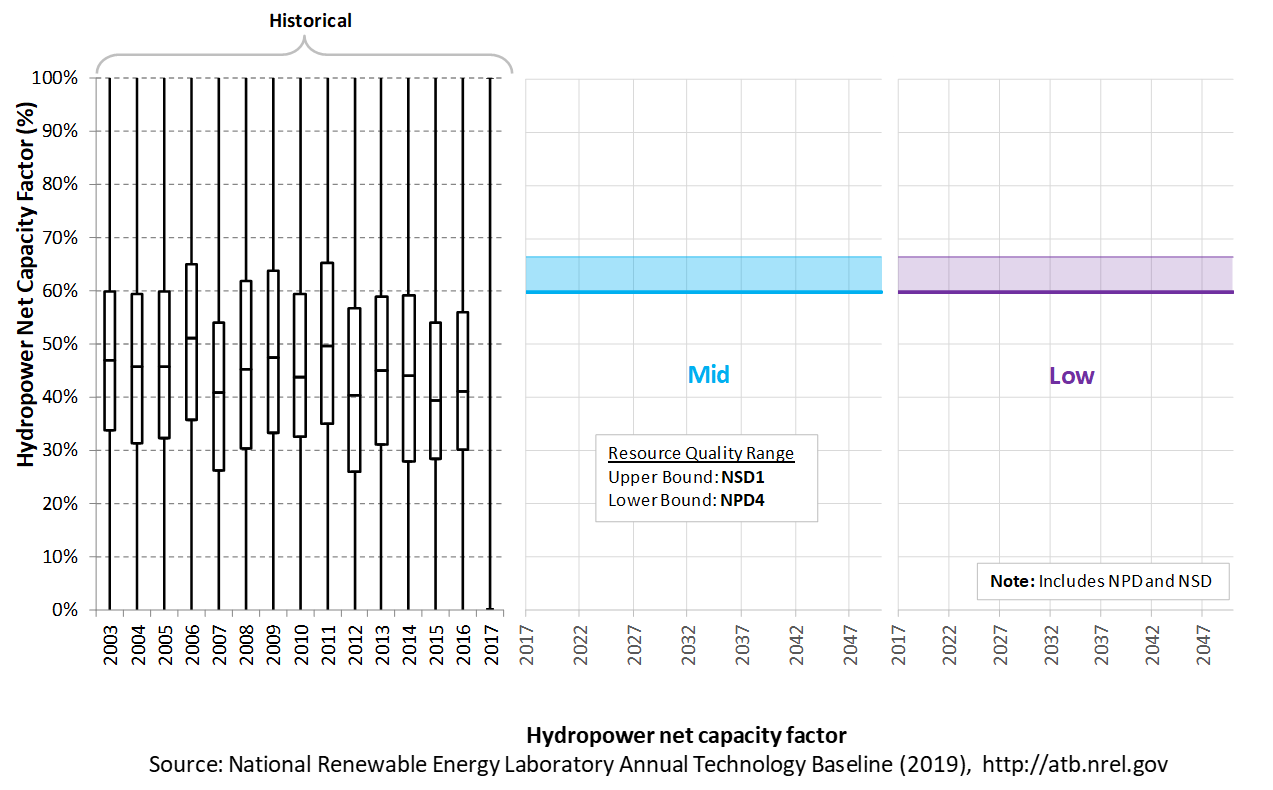

The capacity factor is based on actual 10-year average energy production reported in EIA 923 forms. Some hydropower facilities lack flexibility and only produce electricity when river flows are adequate. Others with storage capabilities are operated to meet a balance between electric system, reservoir management, and environmental needs using their dispatch capability.

No future cost and performance projections for hydropower upgrades are assumed.

Upgrade cost and performance are not illustrated in this documentation of the ATB for the sake of simplicity.

Standard Scenarios Model Results

ATB CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor assumptions for the Base Year and future projections through 2050 for Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios are used to develop the NREL Standard Scenarios using the ReEDS model. See ATB and Standard Scenarios.

Upgrade potential becomes available in the ReEDS model at the relicensing date, end of plant life (50 years), or both.

Representative Technology

Non-powered dams (NPD) are classified by energy potential in terms of head. Low head facilities have design heads below 20 m and typically exhibit the following characteristics (DOE, 2016) :

- 1 MW to 10 MW

- New/rehabilitated intake structure

- Little, if any, new penstock

- Axial-flow or Kaplan turbines (2-4 units)

- New powerhouse (indoor)

- New/rehabilitated tailrace

- Minimal new transmission (< 5 miles, if required)

- Capacity factor of 35% to 60%.

High head facilities have design heads above 20 m and typically exhibit the following characteristics (DOE, 2016) :

- 5 MW to 30 MW

- New/rehabilitated intake structure

- New penstock (typically < 500 feet of steel penstock, if required)

- Francis turbines (1-3 units)

- New powerhouse (indoor)

- New/rehabilitated tailrace

- Minimal new transmission line (up to 15 MW, if required)

- Capacity factor of 35% to 60%.

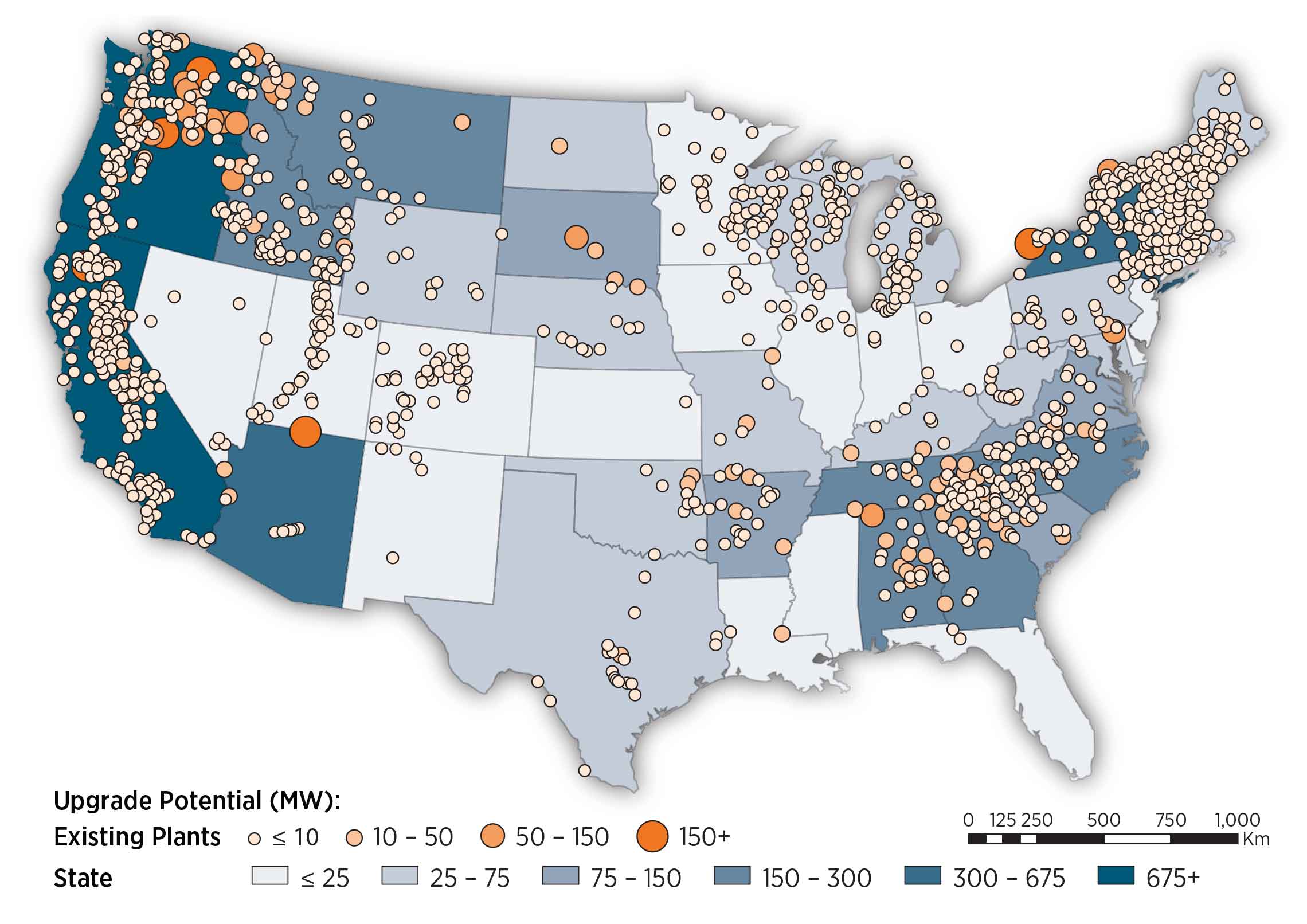

Resource Potential

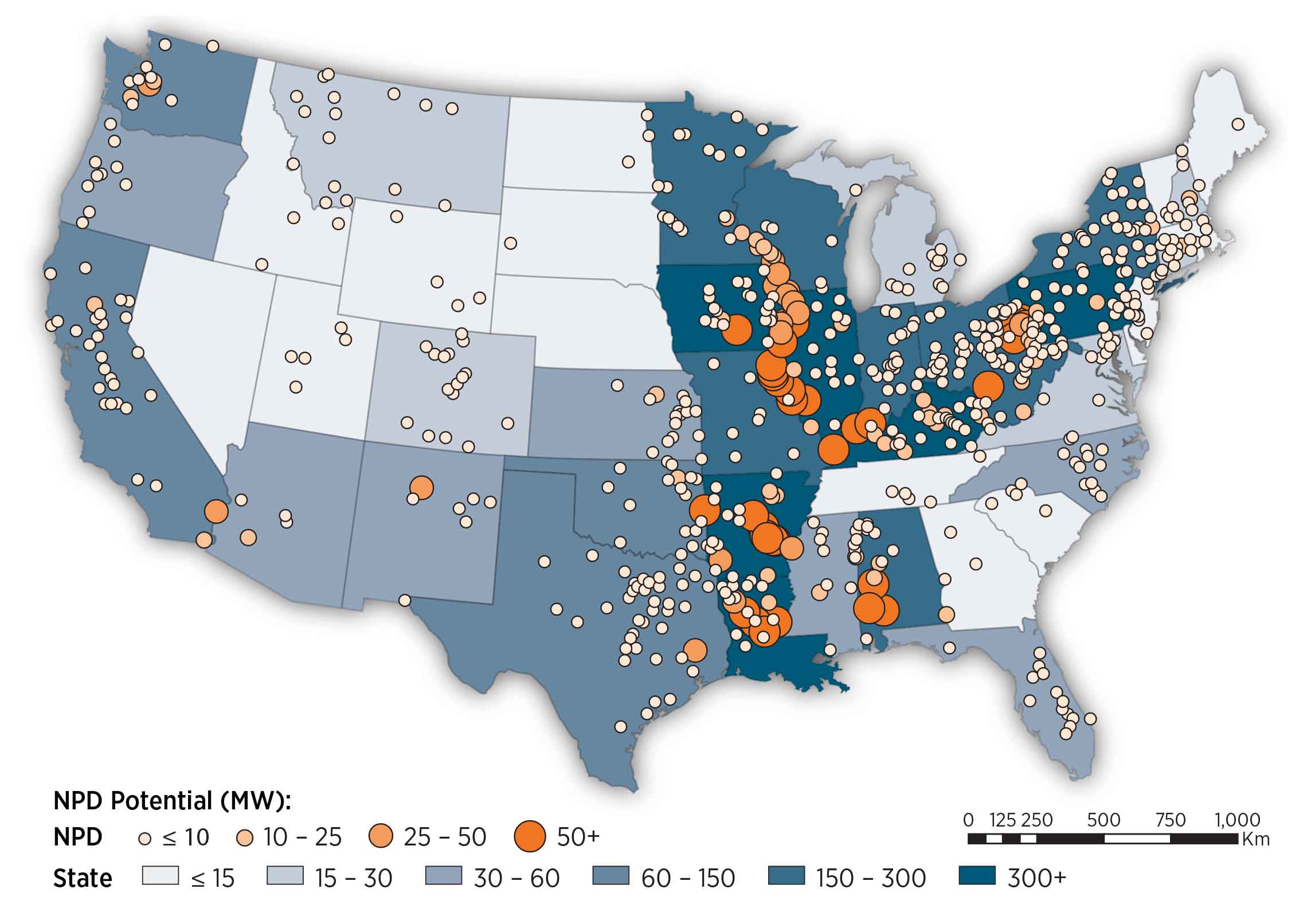

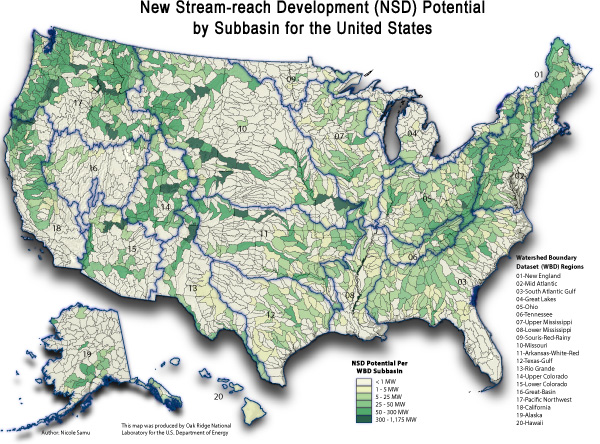

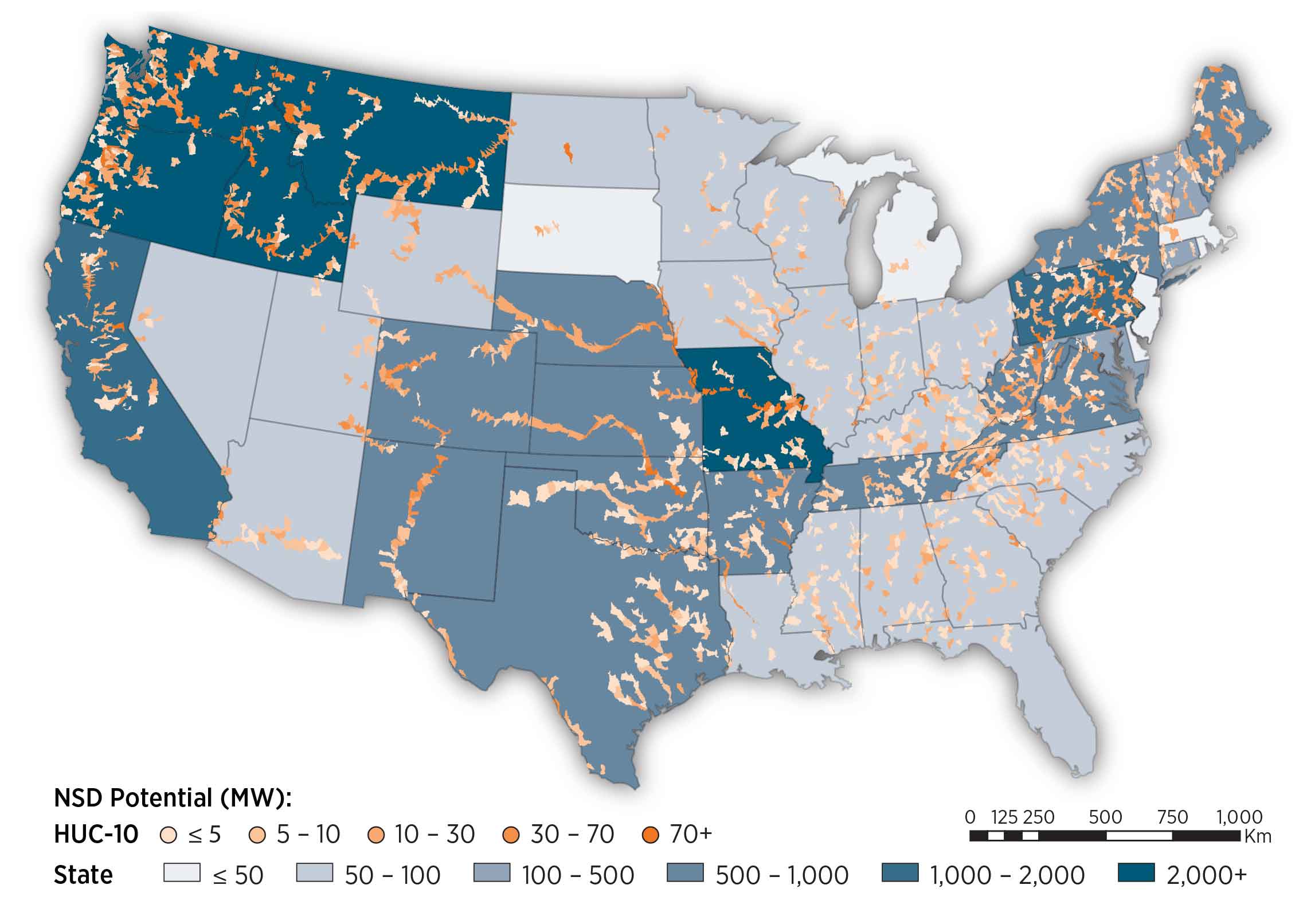

Up to 12 GW of technical potential exists to add power to U.S. NPD. However, based on financial decisions in recent development activity, the economic potential of NPD may be approximately 5.6 GW at more than 54,000 dams in the contiguous United States. Most of this potential (5 GW or 90% of resource capacity) is associated with less than 700 dams. These resource considerations are discussed below:

According to the National

Inventory of Dams, more than 80,000 dams exist that do not produce

power. This data set was filtered to remove dams with erroneous flow

and geographic data and dams whose data could not be resolved to a

satisfactory level of detail

A new methodology for sizing potential hydropower facilities that was developed for the new-stream reach development resource (Kao et al., 2014) was applied to non-powered dams. This resource potential was estimated to be 5.6 GW at more than 54,000 dams. In the development of the Hydropower Vision, the NPD resource available to the ReEDS model was adjusted based on recent development activity and limited to only those projects with power potential of 500 kW or more. As the ATB uses the Hydropower Vision supply curves, this results in a final resource potential of 5 GW/29 TWh from 671 dams.

For each facility, a design capacity, average monthly flow rate over a 30-year period, and a design flow rate exceedance level of 30% are assumed. The exceedance level represents the fraction of time that the design flow is exceeded. This parameter can be varied and results in different capacity and energy generation for a given site. The value of 30% was chosen based on industry rules of thumb. The capacity factor for a given facility is determined by these design criteria.

Design capacity and flow rate dictate capacity and energy generation potential. All facilities are assumed sized for 30% exceedance of flow rate based on long-term, average monthly flow rates.

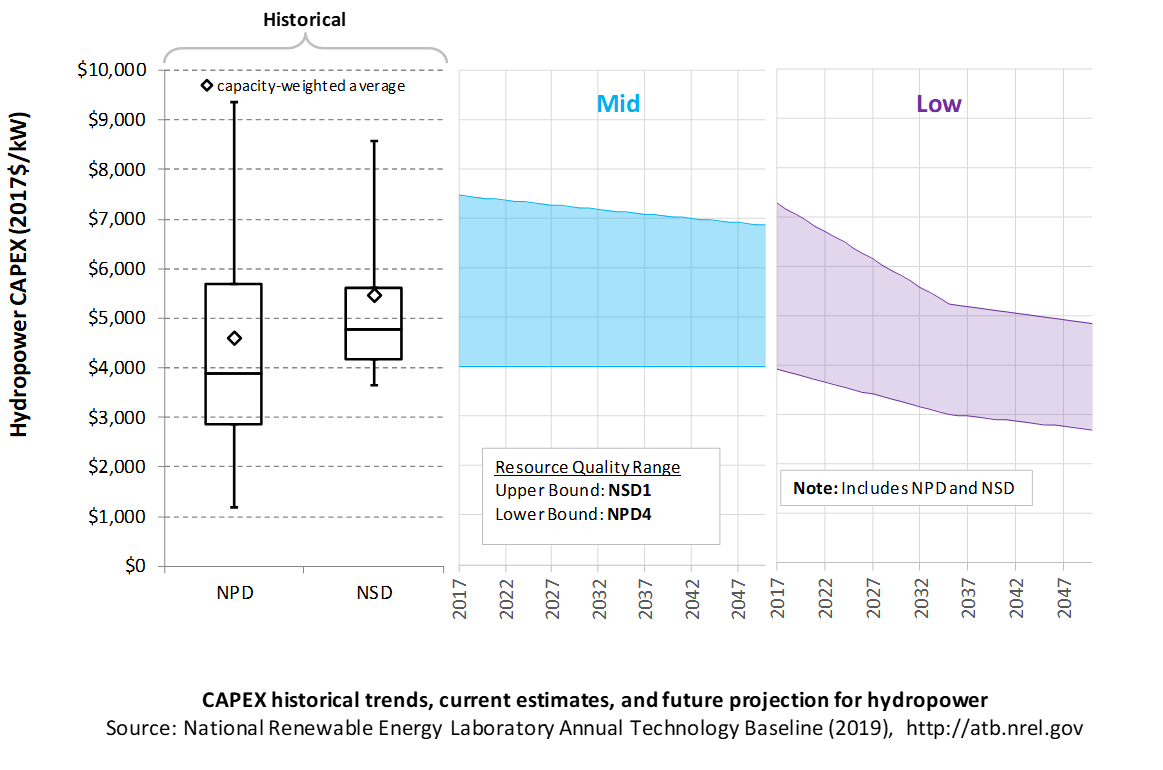

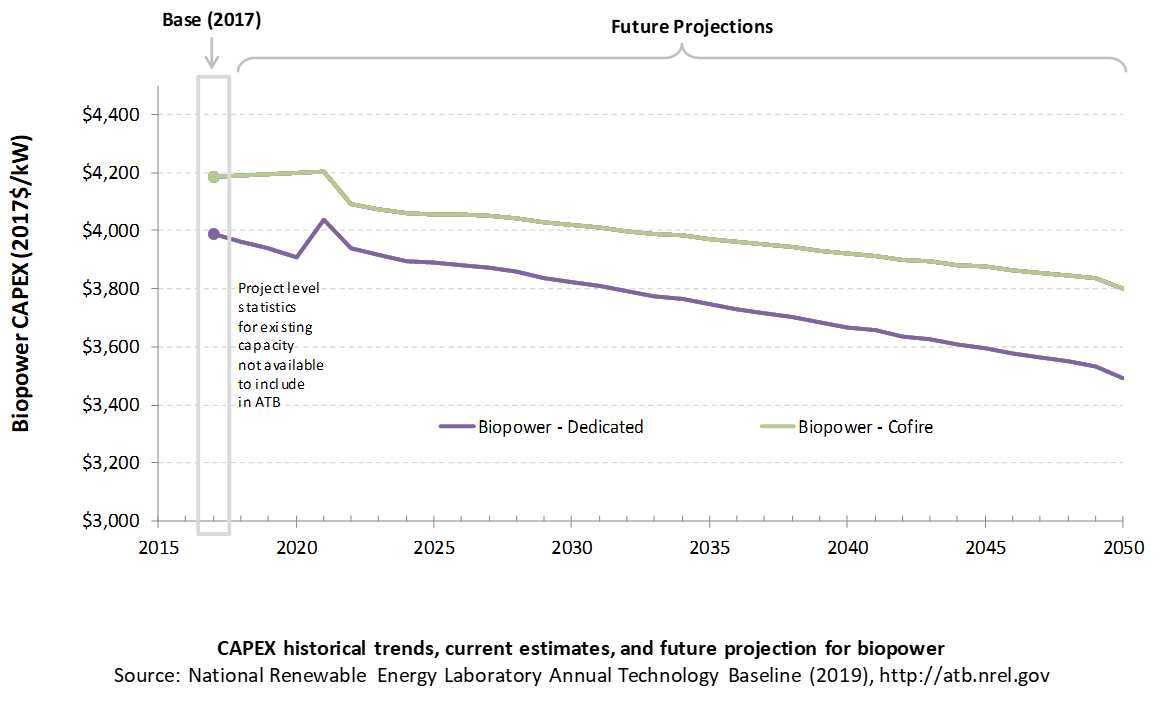

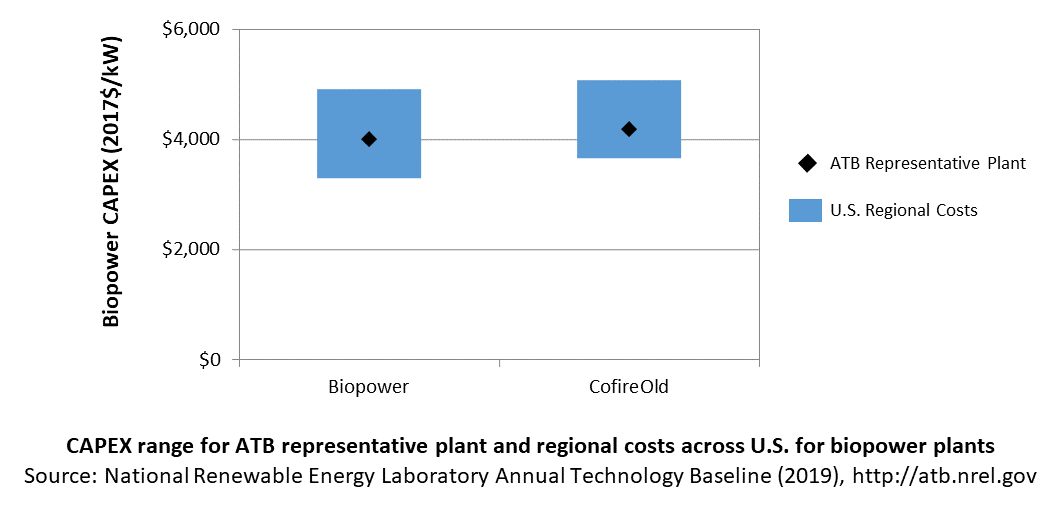

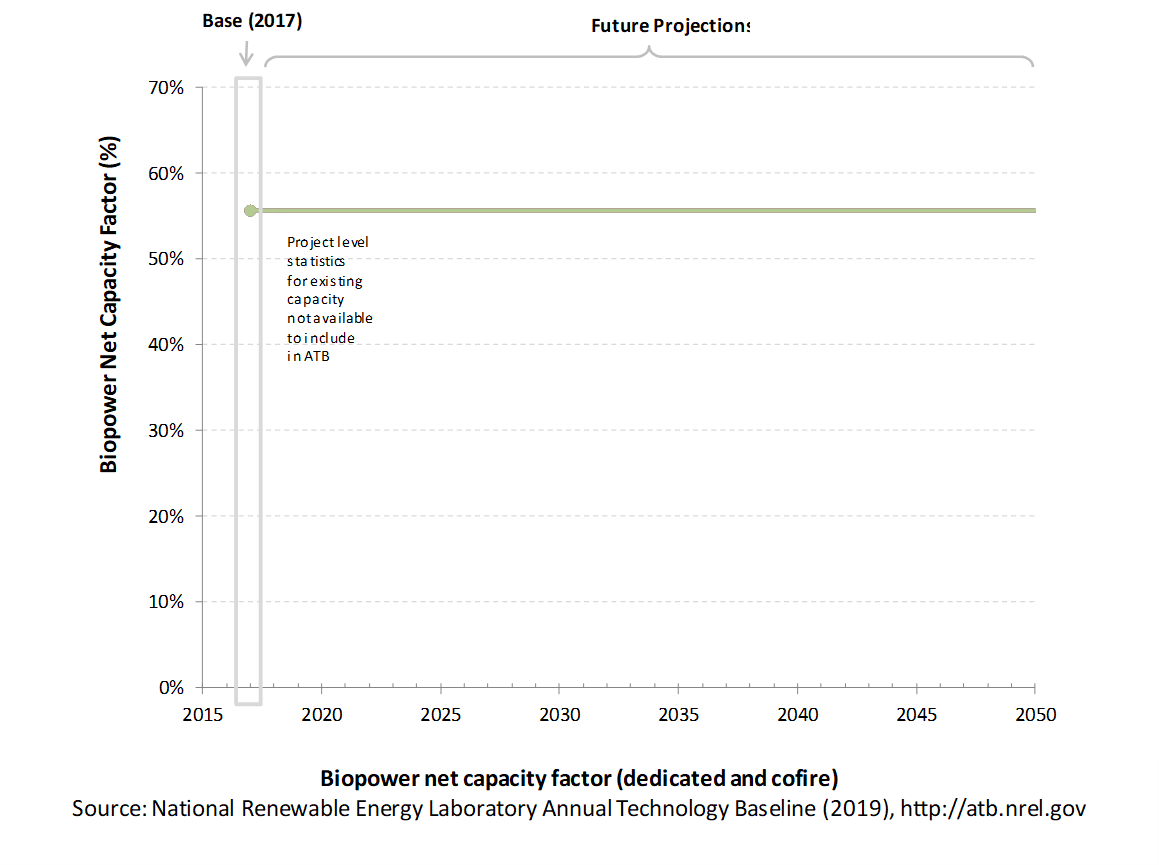

Base Year and Future Year Projections Overview

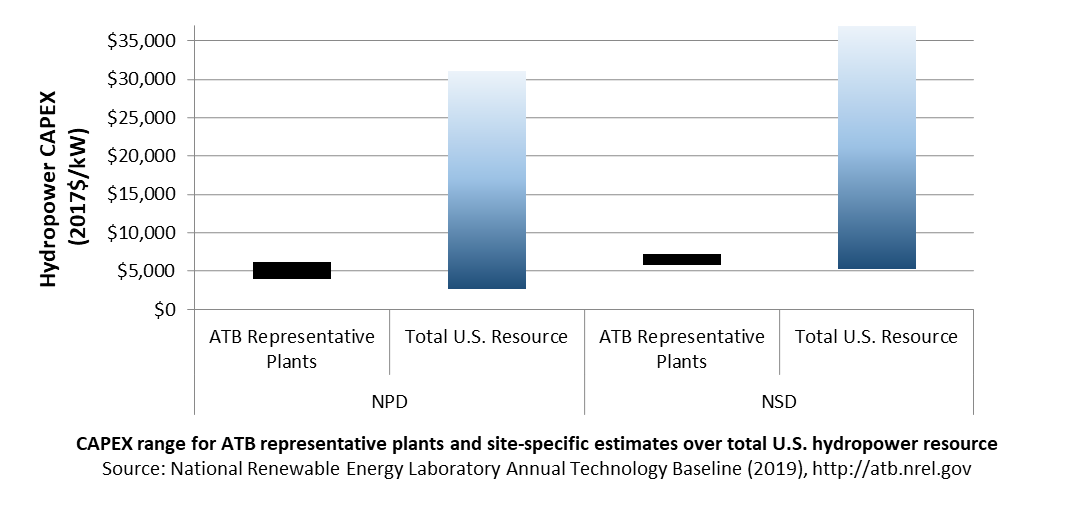

Site-specific CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor estimates are made

for each site in the available resource potential. CAPEX and O&M

estimates are made based on statistical analysis of historical plant

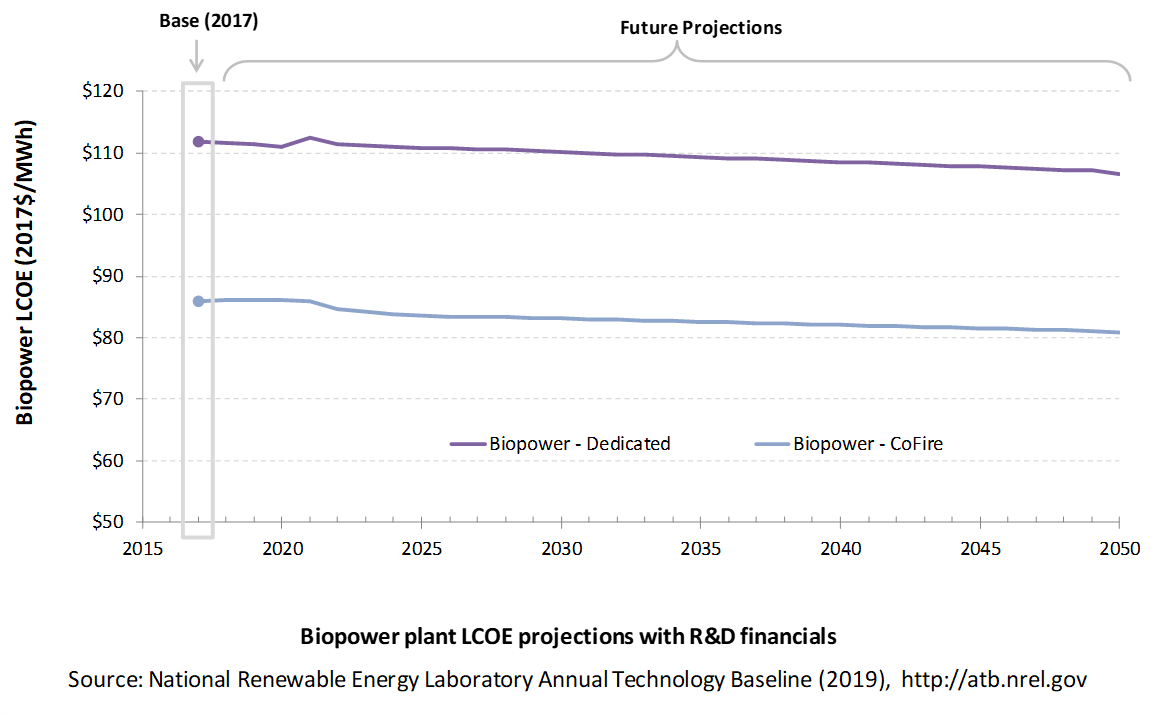

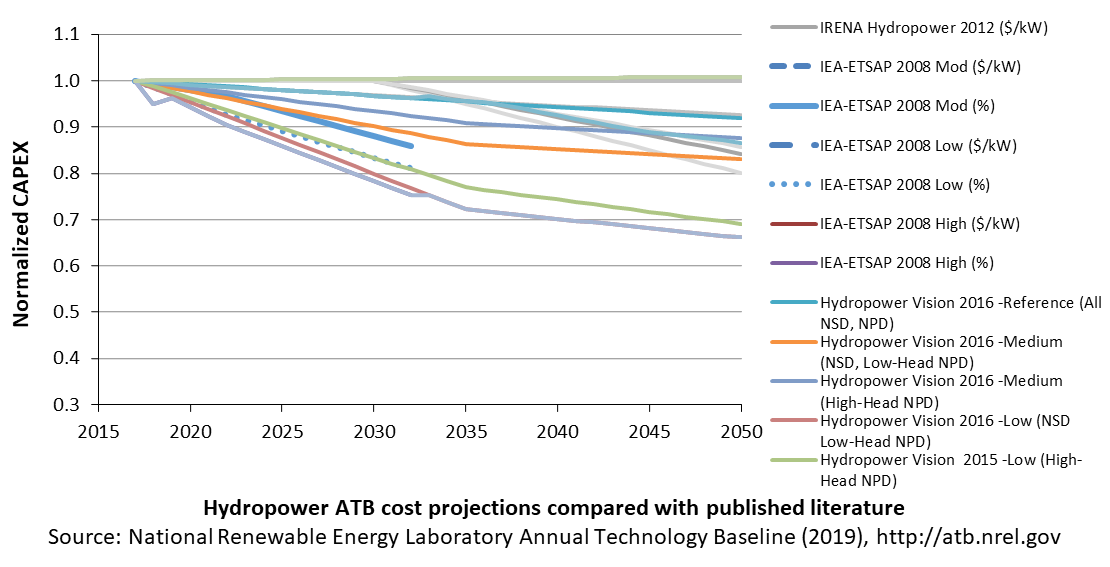

data from 1980 to 2015