Annual Technology Baseline 2018

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Recommended Citation:

NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory). 2018. 2018 Annual Technology Baseline. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. http://atb.nrel.gov/.

Please consult Guidelines for Using ATB Data:

https://atb.nrel.gov/electricity/user-guidance.html

Natural Gas Plants

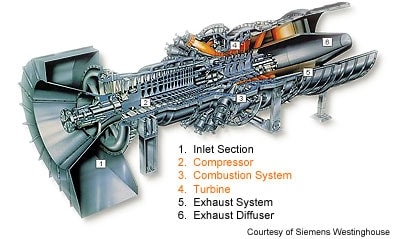

A gas-fired combustion turbine involves:

- An air compressor compresses air and feeds it into the combustion chamber at hundreds of miles per hour.

- In a combustion system, a ring of fuel injectors inject fuel into combustion chambers where it mixes with the air and is combusted. The resulting high-temperature, high-pressure gas stream enters and expands through the turbine.

- A turbine has alternate stationary and rotating airfoil-section blades that are driven by expanding hot combustion gas. The rotating blades drive the compressor and spin a generator to produce electricity.

Simple-cycle gas turbines can achieve 20%-35% energy conversion efficiency depending on the type and design of the system. Aeroderivative turbines are typically more flexible but more expensive than their industrial gas turbine counterparts. Combined-cycle natural gas plants include a heat recovery steam generator that uses the hot exhaust from the combustion turbine to generate steam. That steam can then be used to generate additional electricity using a steam turbine. Combined-cycle natural gas plants typically have efficiencies ranging from 50%-60%, and R&D targets have been set to achieve even higher efficiencies. Combined-cycle plants can be built using a variety of configurations, such as a single combustion turbine and steam turbine connected to a single generator (1x1) or two combustion turbines coupled with one steam turbine (2x1) (DOE "How Gas Turbine Power Plants Work").

Renewable energy technical potential, as defined by Lopez et al. 2012, represents the achievable energy generation of a particular technology given system performance, topographic limitations, and environmental and land-use constraints. Technical resource potential corresponds most closely to fossil reserves, as both can be characterized by the prospect of commercial feasibility and depend strongly on available technology at the time of the resource assessment. Natural gas reserves in the United States are assessed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS, National Oil and Gas Assessment).

This section focuses on large, utility-scale natural gas plants. Distributed-scale turbines may be included in a future version of the ATB.

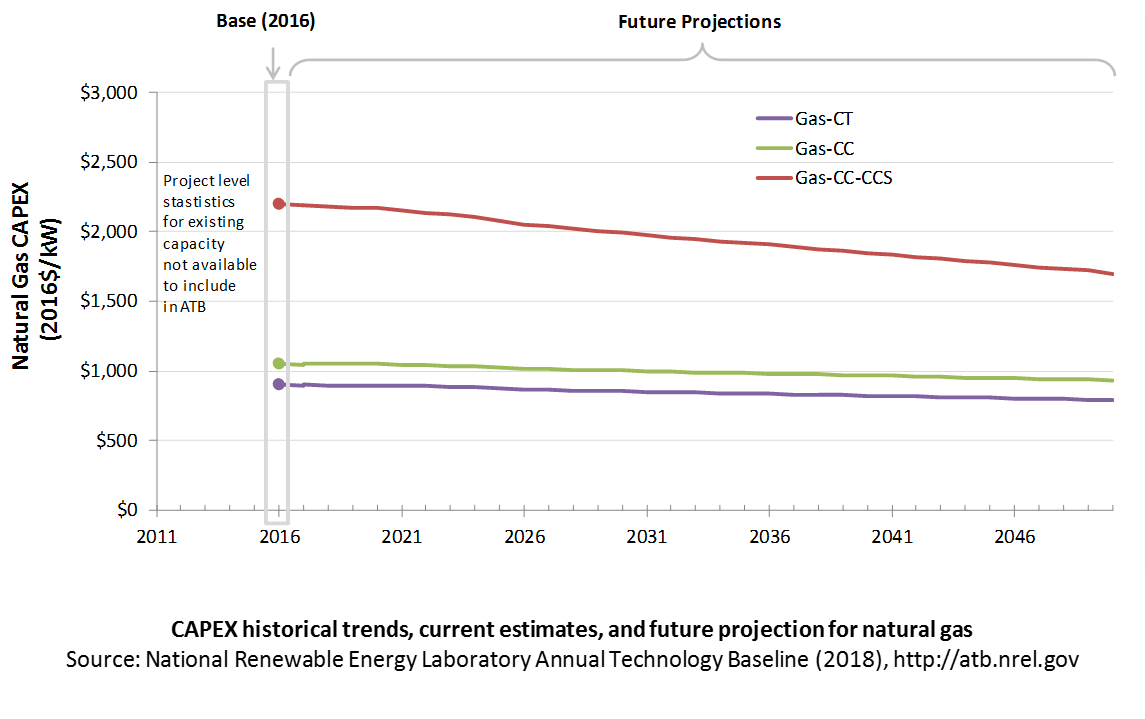

CAPital EXpenditures (CAPEX): Historical Trends, Current Estimates, and Future Projections

Because natural gas plants are well-known and perform close to their optimal performance, the EIA capital expenditures (CAPEX) projections decline at the minimum learning rate for the gas-fired technologies, resulting in incremental improvement over time that progresses slightly more quickly than inflation.

The one exception is natural gas combined cycle (CC) with carbon capture and storage (CCS). The DOE Office of Fossil Energy and the National Energy Technology Laboratory conduct research on reducing the costs and increasing the performance of CCS technology, and costs are expected to decline over time at a higher learning rate than the more mature gas-CT and gas-CC technologies.

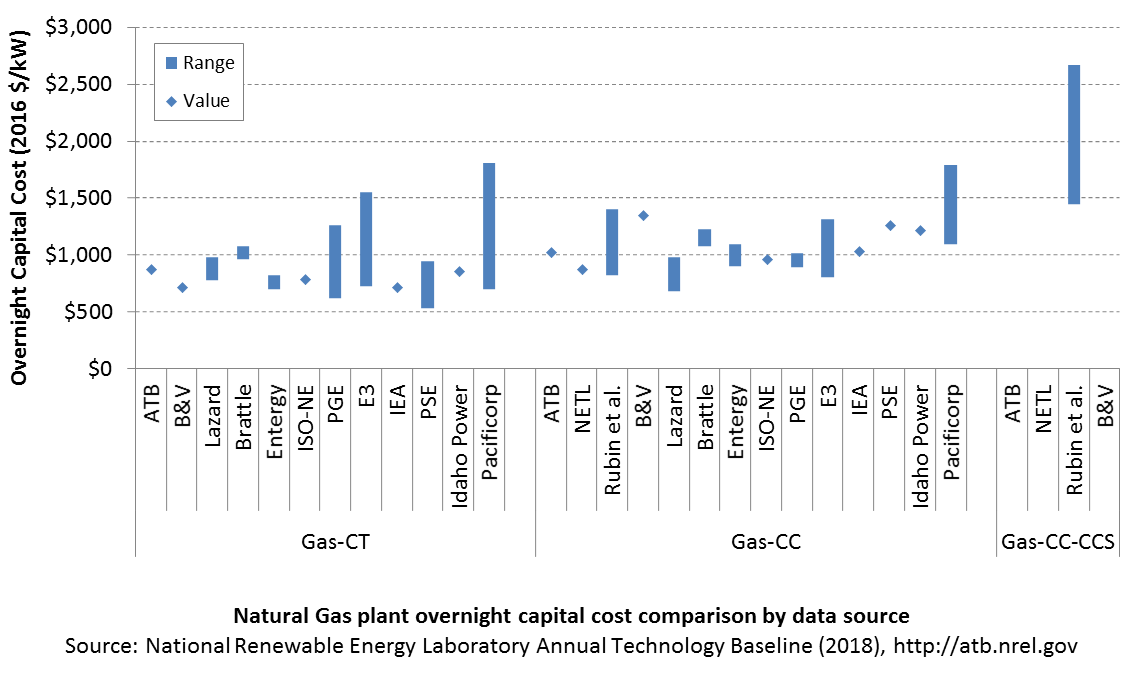

Comparison with Other Sources

Costs vary due to differences in configuration (e.g., 2x1 versus 1x1), turbine class, and methodology. All costs were converted to the same dollar year.

CAPEX Definition

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) are expenditures required to achieve commercial operation in a given year.

Overnight capital costs are modified from EIA (2017). Capital costs include overnight capital cost plus defined transmission cost, and it removes a material price index.

Fuel costs are taken from EIA (2017). EIA reports two types of gas-CT and gas-CC technologies in EIA's Annual Energy Outlook: advanced (H-class for gas-CC, F-class for gas-CT) and conventional (F-class for gas-CC, LM-6000 for gas-CT). Because we represent a single gas-CT and gas-CC technology in the ATB, the characteristics for the ATB plants are taken to be the average of the advanced and conventional systems as reported by EIA. For example, the OCC for the gas-CC technology in the ATB is the average of the capital cost of the advanced and conventional combined cycle technologies from the Annual Energy Outlook. Future work aims to improve the representation of the various natural gas technologies in the ATB. The CCS plant configuration includes only the cost of capturing and compressing the CO2. It does not include CO2 delivery and storage.

| Overnight Capital Cost ($/kW) | Construction Financing Factor (ConFinFactor) | CAPEX ($/kW) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas-CT:Conventional combustion turbine | $864 | 1.021 | $882 |

| Gas-CC:Conventional combined cycle | $1,010 | 1.021 | $1,032 |

| Gas-CC-CCS:Combined cycle with carbon capture sequestration | $2,109 | 1.021 | $2,154 |

CAPEX can be determined for a plant in a specific geographic location as follows:

Regional cost variations and geographically specific grid connection costs are not included in the ATB (CapRegMult = 1; GCC = 0). In the ATB, the input value is overnight capital cost (OCC) and details to calculate interest during construction (ConFinFactor).

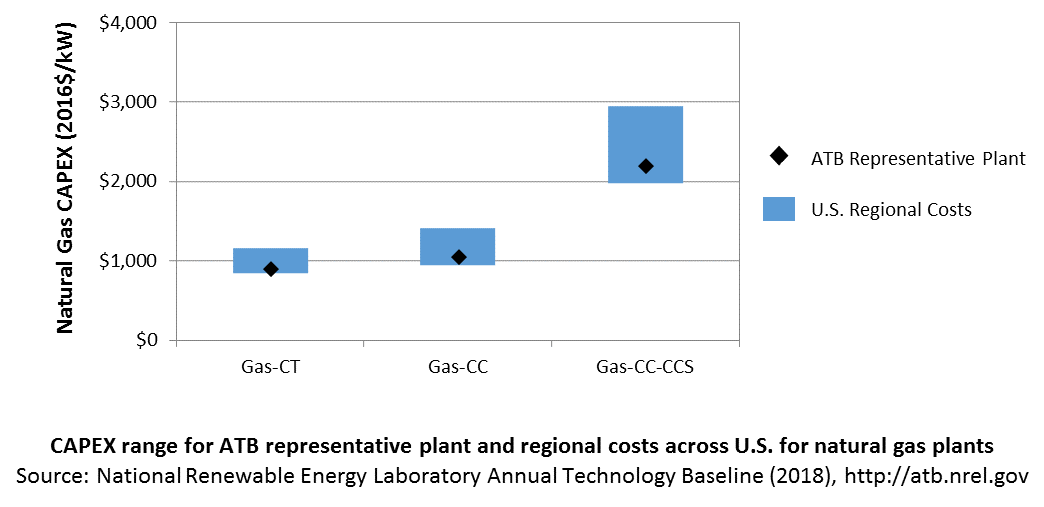

In the ATB, CAPEX represents each type of gas plant with a unique value. Regional cost effects associated with labor rates, material costs, and other regional effects as defined by EIA 2016a expand the range of CAPEX. Unique land-based spur line costs based on distance and transmission line costs are not estimated. The following figure illustrates the ATB representative plant relative to the range of CAPEX including regional costs across the contiguous United States. The ATB representative plants are associated with a regional multiplier of 1.0.

Natural Gas Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle

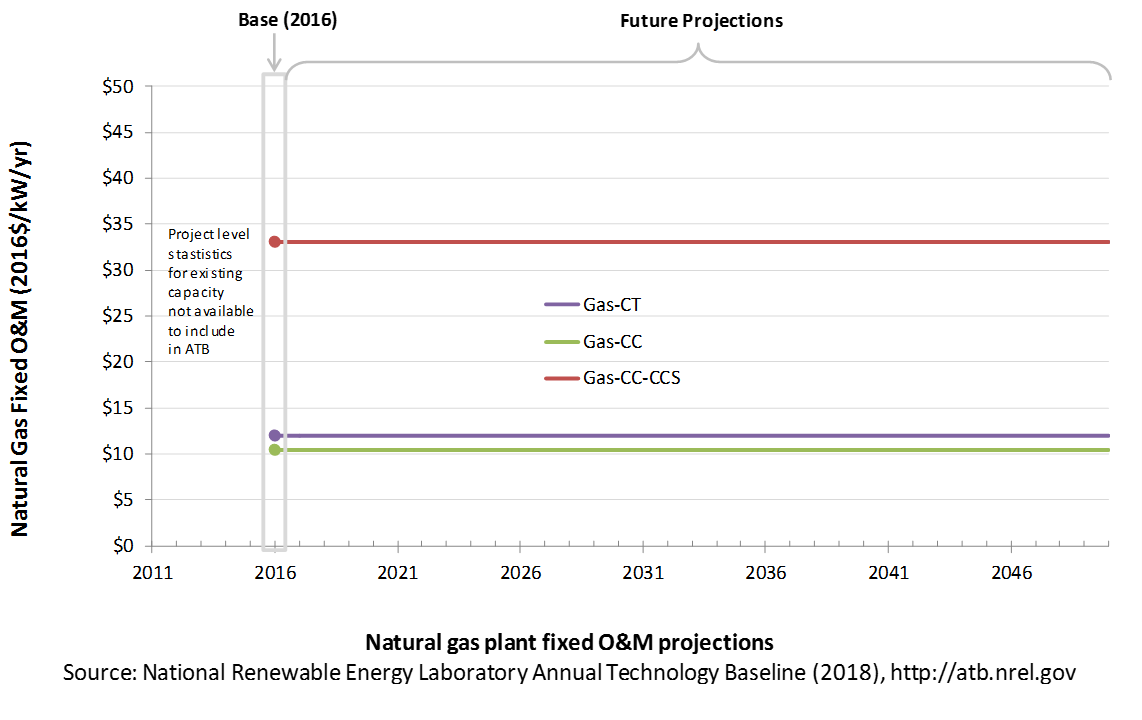

Operations and maintenance (O&M) costs represent the annual expenditures required to operate and maintain a plant over its lifetime, including:

- Insurance, taxes, land lease payments, and other fixed costs

- Present value and annualized large component replacement costs over technical life

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance of power plants, transformers, and other components over the technical lifetime of the plant.

Market data for comparison are limited and generally inconsistent in the range of costs covered and the length of the historical record.

Capacity Factor: Expected Annual Average Energy Production Over Lifetime

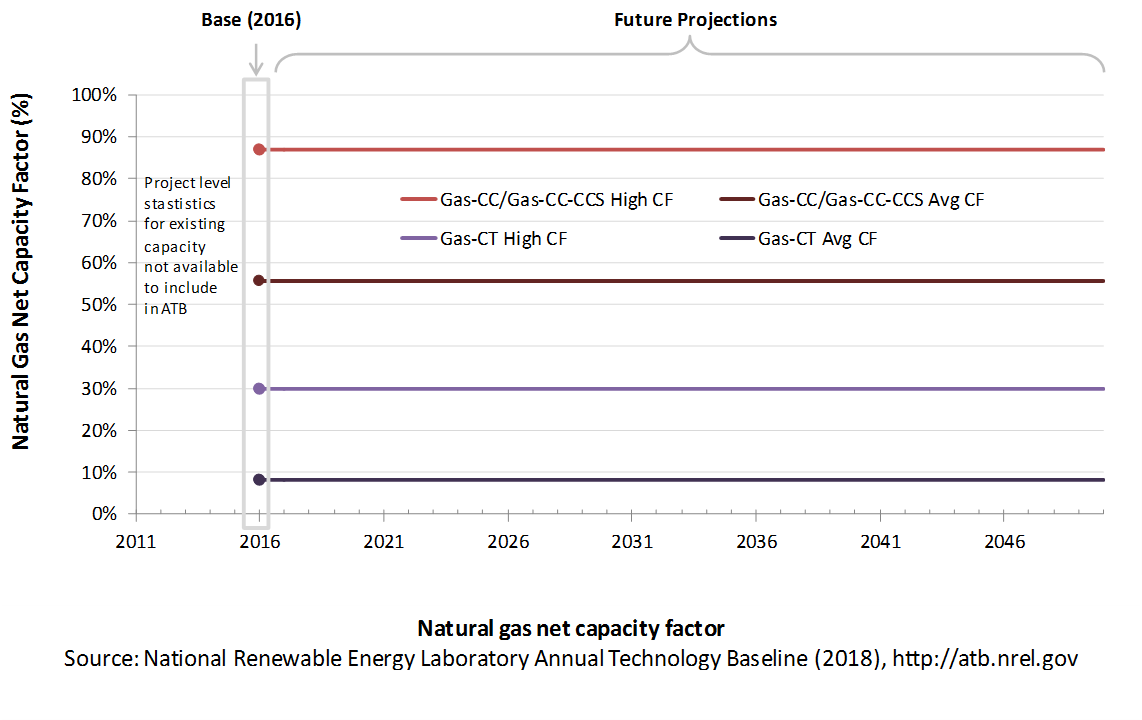

The capacity factor represents the assumed annual energy production divided by the total possible annual energy production, assuming the plant operates at rated capacity for every hour of the year. For natural gas plants, the capacity factor is typically lower (and, in the case of combustion turbines, much lower) than their availability factor. Natural gas plants have availability factors approaching 100%.

The capacity factors of dispatchable units is typically a function of the unit's marginal costs and local grid needs (e.g., need for voltage support or limits due to transmission congestion). The average capacity factor is the average fleet-wide capacity factor for these plant types in 2015. The high capacity factor is taken from EIA (2018, Table 1a) for a new power plant and represents a high bound of operation for a plant of this type.

Gas-CT power plants are less efficient than gas-CC power plants, and they tend to run as intermediate or peaker plants.

Gas-CC with CCS has not yet been built. It is expected to be a baseload unit.

Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) Projections

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a simple metric that combines the primary technology cost and performance parameters: CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor. It is included in the ATB for illustrative purposes. The ATB focuses on defining the primary cost and performance parameters for use in electric sector modeling or other analysis where more sophisticated comparisons among technologies are made. The LCOE accounts for the energy component of electric system planning and operation. The LCOE uses an annual average capacity factor when spreading costs over the anticipated energy generation. This annual capacity factor ignores specific operating behavior such as ramping, start-up, and shutdown that could be relevant for more detailed evaluations of generator cost and value. Electricity generation technologies have different capabilities to provide such services. For example, wind and PV are primarily energy service providers, while the other electricity generation technologies provide capacity and flexibility services in addition to energy. These capacity and flexibility services are difficult to value and depend strongly on the system in which a new generation plant is introduced. These services are represented in electric sector models such as the ReEDS model and corresponding analysis results such as the Standard Scenarios.

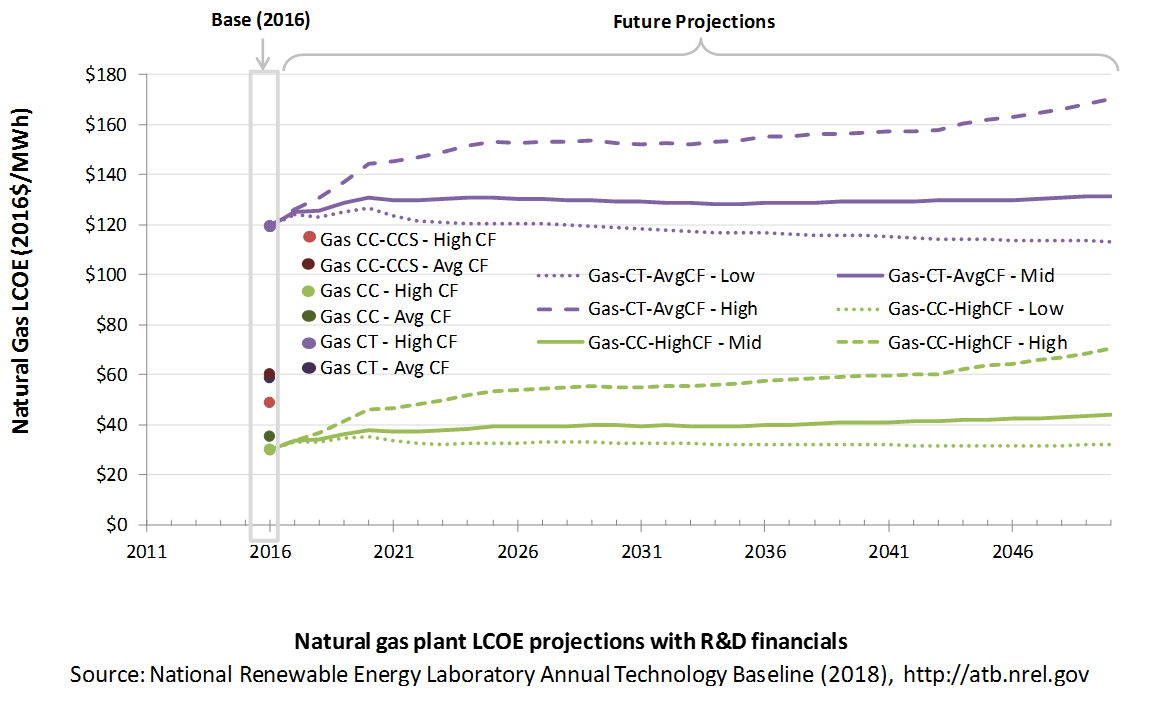

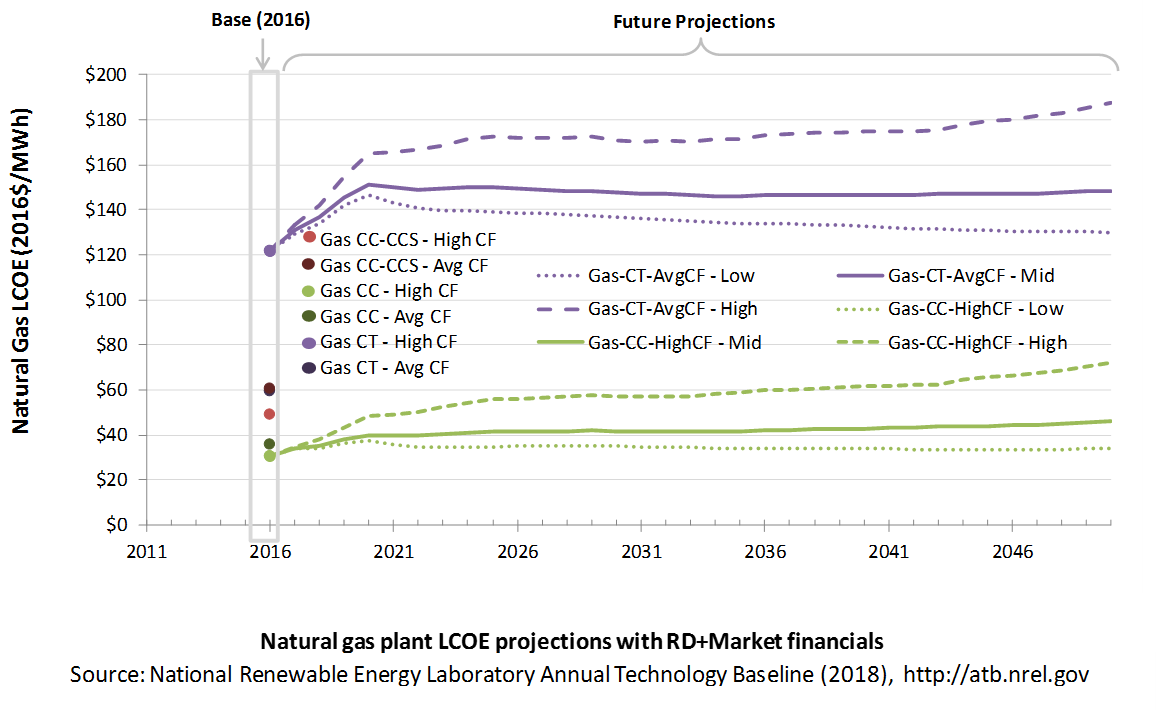

The following three figures illustrate LCOE, which includes the combined impact of CAPEX, O&M, and capacity factor projections for natural gas across the range of resources present in the contiguous United States. For the purposes of the ATB, the costs associated with technology and project risk in the U.S. market are represented in the financing costs, not in the upfront capital costs (e.g. developer fees, contingencies). An individual technology may receive more favorable financing terms outside of the U.S., due to less technology and project risk, caused by more project development experience (e.g. offshore wind in Europe), or more government or market guarantees. The R&D Only LCOE sensitivity cases present the range of LCOE based on financial conditions that are held constant over time unless R&D affects them, and they reflect different levels of technology risk. This case excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, technology-specific tariffs, and changing interest rates over time. The R&D + Market LCOE case adds to these the financial assumptions (1) the changes over time consistent with projections in the Annual Energy Outlook and (2) the effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs. The ATB representative plant characteristics that best align with those of recently installed or anticipated near-term natural gas plants are associated with Gas-CC-HighCF. Data for all the resource categories can be found in the ATB data spreadsheet.

R&D Only | R&D + Market

The LCOE of natural gas plants is directly impacted by the price of the natural gas fuel, so we include low, median, and high natural gas price trajectories. The LCOE is also impacted by variations in the heat rate and O&M costs. Because the reference and high natural gas price projections from AEO 2017 are rising over time, the LCOE of new natural gas plants can actually increase over time if the gas prices rise faster than the capital costs decline. For a given year, the LCOE assumes that the fuel prices from that year continue throughout the lifetime of the plant.

These projections do not include any cost of carbon, which would influence the LCOE of fossil units. Also, for CCS plants, the potential revenue from selling the captured carbon is not included (e.g., enhanced oil recovery operation may purchase CO2 from a CCS plant).

Fuel prices are based on the AEO 2017 (EIA 2017).

To estimate LCOE, assumptions about the cost of capital to finance electricity generation , and the LCOE calculations are sensitive to these financial assumptions. Three project finance structures are used within the ATB:

- R&D Only Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case allows technology-specific changes to debt interest rates, return on equity rates, and debt fraction to reflect effects of R&D on technological risk perception, but it holds background rates constant at 2016 values from AEO 2018 and excludes effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs. A constant cost recovery period-or period over which the initial capital investment is recovered-of 30 years is assumed for all technologies.

- R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions: This sensitivity case retains the technology-specific changes to debt interest, return on equity rates, and debt fraction from the R&D Only case and adds in the variation over time consistent with AEO 2018, as well as effects of tax reform, tax credits, and tariffs. As in the R&D Only case, a constant cost recovery period-or period over which the initial capital investment is recovered-of 30 years is assumed for all technologies. For a detailed discussion of these assumptions, see Changes from 2017 ATB to 2018 ATB.

- ReEDS Financial Assumptions: ReEDS uses the R&D Only + Market Financial Assumptions for the "Mid" technology cost scenario.

These parameters are allowed to vary by year. The equations and variables used to estimate LCOE are defined on the equations and variables page. For illustration of the impact of changing financial structures such as WACC, see Project Finance Impact on LCOE. For LCOE estimates for the Constant, Mid, and Low technology cost scenarios for all technologies, see 2018 ATB Cost and Performance Summary.

References

Annual Energy Outlook 2017 with Projections to 2050. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy. January 5, 2017. http://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/0383(2017).pdf.

B&V (Black & Veatch). 2012. Cost and Performance Data for Power Generation Technologies. Black & Veatch Corporation. February 2012. http://bv.com/docs/reports-studies/nrel-cost-report.pdf.

E3 (Energy and Environmental Economics). 2014. Capital Cost Review of Power Generation Technologies: Recommendations for WECC's 10- and 20-Year Studies. Prepared for the Western Electric Coordinating Council. https://www.wecc.biz/Reliability/2014_TEPPC_Generation_CapCost_Report_E3.pdf.

EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration). 2016a. Capital Cost Estimates for Utility Scale Electricity Generating Plants. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy. November 2016. https://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/powerplants/capitalcost/pdf/capcost_assumption.pdf.

EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration). 2018. Annual Energy Outlook 2018 with Projections to 2050. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Energy. February 6, 2018. https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/AEO2018.pdf.

Entergy. 2015. Entergy Arkansas, Inc.: 2015 Integrated Resource Plan. July 15, 2015. http://entergy-arkansas.com/content/transition_plan/IRP_Materials_Compiled.pdf.

IEA (International Energy Agency). 2015a. Projected Costs of Generating Electricity: 2015 Edition. Paris: International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/media/presentations/150831_ProjectedCostsOfGeneratingElectricity_Presentation.pdf.

ISO-NE (ISO New England). 2016. ISO-NE CONE and ORTP Analysis. September 13, 2016. http://www.iso-ne.com/static-assets/documents/2016/09/a7_cone_ortp_concentric_energy_advisors.pptx.

Lazard. 2016. Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis-Version 10.0. December 2016. New York: Lazard. https://www.lazard.com/media/438038/levelized-cost-of-energy-v100.pdf.

Lopez, Anthony, Billy Roberts, Donna Heimiller, Nate Blair, and Gian Porro. 2012. U.S. Renewable Energy Technical Potentials: A GIS-Based Analysis. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-6A20-51946. http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy12osti/51946.pdf.

NETL (National Energy Technology Laboratory: Tim Fout, Alexander Zoelle, Dale Keairns, Marc Turner, Mark Woods, Norma Kuehn, Vasant Shah, Vincent Chou, Lora Pinkerton). 2015. Fossil Energy Plants: Volume 1a: Bituminous Coal (PC) and Natural Gas to Electricity, Revision 3. DOE/NETL-2015/1723. http://www.netl.doe.gov/File%20Library/Research/Energy%20Analysis/Publications/Rev3Vol1aPC_NGCC_final.pdf.

Newell, Samuel A., J. Michael Hagerty, Kathleen Spees, Johannes P. Pfeifenberger, Quincy Liao, Christopher D. Ungate, and John Wroble. 2014. Cost of New Entry Estimates for Combustion Turbine and Combined Cycle Plants in PJM. Cambridge: The Brattle Group. May 15, 2014. http://www.brattle.com/system/publications/pdfs/000/005/010/original/Cost_of_New_Entry_Estimates_for_Combustion_Turbine_and_Combined_Cycle_Plants_in_PJM.pdf?1400252453.

PGE (Portland General Electric). 2015. Integrated Resource Plan 2016. July 16, 2015. https://www.portlandgeneral.com/-/media/public/our-company/energy-strategy/documents/2015-07-16-public-meeting.pdf.

PSE (Puget Sound Energy). 2016. 2017 IRP Supply-Side Resource Advisory Committee: Thermal. July 25, 2016. https://pse.com/aboutpse/EnergySupply/Documents/IRP_07-25-2016_Presentations.pdf.

Rubin, Edward S., Inês M.L. Azevedo, Paulina Jaramillo, and Sonia Yeh. 2015. "A Review of Learning Rates for Electricity Supply Technologies." Energy Policy 86 (November 2015): 198–218. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421515002293.